Many books have been written about structure in filmmaking and how to build a story. Many filmmakers follow such structures and make great films. Then there are those that throw such structures out the window and make up their own rules. They take a risk and it works out. Some of these films became instant classics, while others received a polarised reaction upon release but have since gone on to gain critical acclaim.

Unlike more straightforward movies that have hidden meanings, these movies are intentionally ambiguous and so dense that they contain multiple interpretations and thus many require multiple viewings.

As each reader will have had a different thoughts on what these films mean and signify, it would be very difficult to rank them on a scale of how good they are. Therefore, these films are ranked in chronological order and spoilers have been avoided where possible.

1. Rashomon (1950, Akira Kurosawa)

It is well known that before filming began, Akira Kurosawa’s three assistant directors came up to him and told him that they did not understand the screenplay. “If you read it diligently,” Kurosawa told them, “you should be able to understand it, because it was written with the intention of being comprehensible.”

Rashomon’s plot follows the story of the murder of a samurai and the rape of his wife in the woods of historical Japan. Told from four different perspectives of The Bandit, The Samurai, The Wife and The Woodcutter, each of the four accounts end up being conflicting and contradictory to the other.

Shot in black and white using natural light, Director of Photography Kazuo Miyagawa crafts images draped in light and shadows which hark back memories to the age of silent cinema.

Receiving mixed reviews in Japan, the film went on to win the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival and the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film, and introduced Japanese Cinema to western audiences, becoming an instant classic.

Over the years film scholars and audiences alike have polarizing interpretations of what light and shadow portrays in the movies, meaning that it truly is up to the viewer to decide what is true and what is false… and what that truth is.

2. Vertigo (1958, Alfred Hitchcock)

Loved by audiences but treated indifferently by critics, Alfred Hitchcock’s status as a filmmaker was re-evaluated as a result of a 1954 Cahiers Du Cinema article by Francois Truffaut, which labelled Alfred Hitchcock amongst other directors as an auteur.

Hitchcock’s 1958 film, like many others on this list, received mixed reviews upon its release but has since been re-evaluated, and in 2012’s Sight and Sound poll replaced Citizen Kane for the title of “The Greatest Film Ever Made.”

The movie tells the story of Scottie (James Stewart), a former police detective who suffers from vertigo. Scottie is hired by a former friend to follow his wife, Madeleine (Kim Novak). Scottie believes that he saw her death, soon after he spots Judy Barton who is the spitting image of Madeleine.

Dealing with themes of obsession, romance, the male gaze and objectification, Hitchcock elevates what could have been a silly thriller into a powerful study of the male ego. This is a great film for aspiring filmmakers, and a masterclass in directing.

3. Persona (1966, Ingmar Bergman)

Writing the film whilst ill in hospital, Ingrid Bergman named the film Persona after the Greek word for mask. The plot follows a stage actress Elizabeth (played by Liv Ullman) who stops speaking in the middle of a live performance. Bibi Andersson plays Alma, the young nurse caring for Elizabeth in an isolated island cottage. Over the course of the movie, Alma confides in Elizabeth and begins to have difficulty in distinguishing her identity from her patients.

Shot in stark black and white and soft light by Sven Nykvist, Persona explores themes of identity, psychology, gender, sexuality and even cinema. Since its release in 1966, it has inspired countless films and filmmakers from Robert Altman to David Lynch.

A quote by film historian Peter Cowie probably says it all: “Everything one says about Persona may be contradicted; the opposite will also be true”. Clocking in at only 84 minutes in length, Persona is so dense with themes and imagery, that the only thing one can be sure about is that it is worth revisiting over and over again.

4. 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968, Stanley Kubrick)

Like so many films that challenged what cinema could be, 2001: A Space Odyssey was so groundbreaking, critics didn’t know what to think of it. Pauline Kael went so far as to accuse Kubrick of forgetting how to make a movie! There is some truth in Kael’s words, 2001: A Space Odyssey lacks a conventional narrative, instead it is comprised of several vignettes ranging from a group of hominids living in an African desert millions of years ago, to a group of NASA scientists on a mission to Jupiter.

Perhaps the best way to describe 2001 is by Roger Ebert’s quote whilst reviewing the film: “The genius is not in how much Stanley Kubrick does in 2001: A Space Odyssey, but in how little”. Forgoing conventional narrative and dialogue, Kubrick instead uses cinematic language that has inspired countless filmmakers in the fifty years since its release, as is evident of it ranking as the 2nd greatest film of all time in the BFI Directors’ top 50 poll.

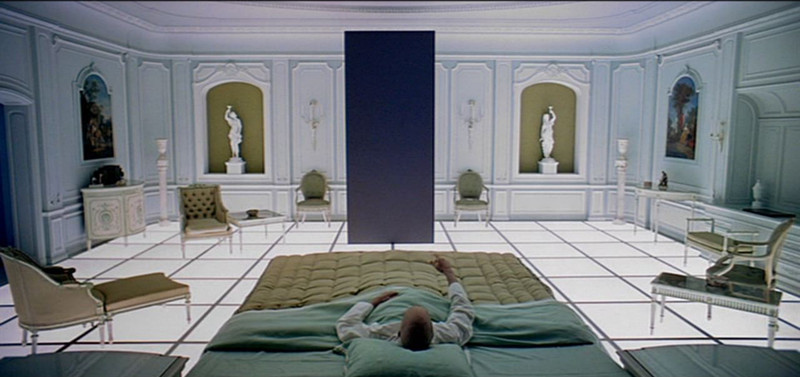

Stanley Kubrick and Arthur C. Clarke wanted to leave the film intentionally ambiguous to allow for a variety of philosophical interpretation depending on the viewer. With unforgettable images that have become iconic such as the monolith, the stargate sequence and the star child, 2001: A Space Odyssey isn’t merely a movie, it is an experience that affects the viewer on a subconscious level and is a must see for every cinephile.

5. The Holy Mountain (1973, Alejandro Jodorowsky)

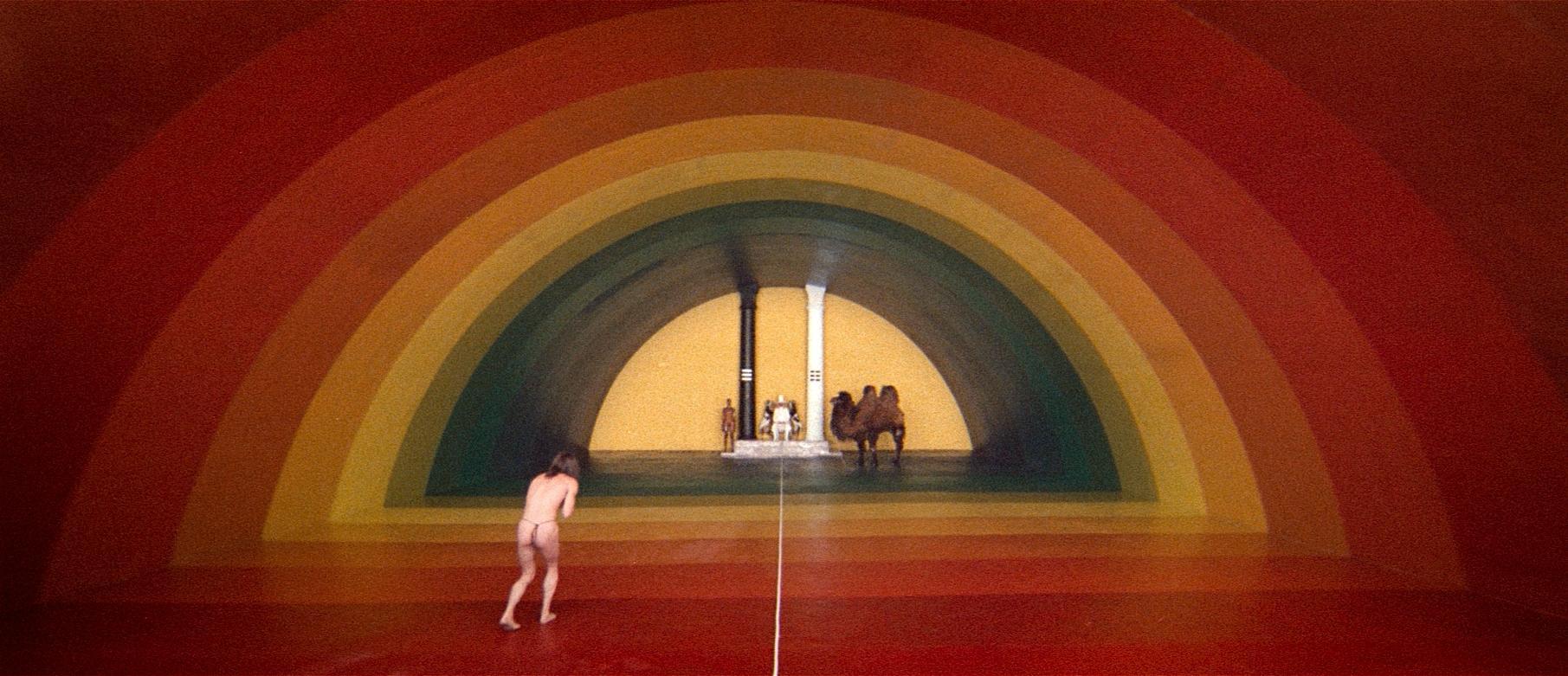

The Holy Mountain tells the story of The Alchemist (Jodorowsky) who accepts a Christ-like figure named ‘The Thief’ as his apprentice and leads him and others to the mysterious mountain in the hopes of achieving enlightenment.

Perhaps one of the most surreal movies ever made, Alejandro Jodorowsky wrote, produced, directed, scored, edited and acted in this fantasy film with one of the most meta endings ever shot on film.

The story of the production is just as crazy and fascinating as the movie itself. Before shooting began, Jodorowsky spent a week without sleep, underwent three months of spiritual exercises and took LSD before shooting began. He also made the cast undergo a similar process and had them take magic mushrooms during pivotal scenes.

A politically charged work, The Holy Mountain is beautiful and profound at times, disgusting and shallow at other moments, but it is a film like no other, and could only have come from an artist like Alejandro Jodorowsky.

6. Stalker (1979, Andrei Tarkovsky)

Andrei Tarkovsky’s last feature film made in the Soviet Union sees the director touch on familiar metaphysical and religious themes. In a post apocalyptic world, a Stalker (Alexander Kaidanovsky) leads two men, simply named Writer and Professor, into a heavily policed, abandoned area known as “The Zone”, a place rumoured to contain a room which can fulfill a man’s deepest wishes.

Stalker was Tarkovsky’s second science fiction feature after Solaris (which he deemed failure) and spent a long time in production due to his insistence on perfection which led to reshooting much of the film.

Shot on different coloured film stocks and famously using only 142 shots throughout the entire 160 minute running time, along with brilliant sound design, Stalker is a film that demands a lot of patience from the viewer, but every frame is bursting with audio-visual information which is worth pondering over long after the film is finished.

7. Eyes Wide Shut (1999, Stanley Kubrick)

Erotic, thought provoking and captivating – Stanley Kubrick’s last film Eyes Wide Shut came twelve years after Full Metal Jacket and was hotly anticipated, in part due to the casting of real life couple Tom Cruise and Nicole Kidman, who were two of the biggest stars in the world at that time.

Based on the 1926 novella “Traumnovelle”, the story follows Dr. Bill Harper (Tom Cruise) who, after finding out his wife, Alice (Nicole Kidman) has fantasized about having sex with another man, embarks on a night time journey through New York that eventually leads him to a masked orgy held by an elite secret society.

Shot as an erotic thriller, the films sees Kubrick using his mastery over filmmaking to create a world that is like a waking dream. Kubrick’s use of colour, Christmas imagery and venetian masks in the film has been heavily discussed as to what they truly signify.

Sadly over the years Kubrick’s last film hasn’t received as much praise and attention as his other films, but Eyes Wide Shut is one of the greatest movies ever made about sex and marriage, and ranks amongst his very best.