Humans fundamentally hate being alone. Come what may, they create bonds, make families, and progressively gather in complex social schemes. Yet, even though most of us choose a life in blinding, noisy and populous cities, lonely people are found everywhere: in the streets, in the bars, in the cafés, maybe in your neighboring apartment.

As Greek writer Antonis Samarakis said quite a long time ago, “Never in times past the roofs of people’s homes were so close to each other as they are today. And never before the hearts of people were as far away from each other as they are today.”

Several forms of modern art have extensively focused on the mentally isolated individuals who have been trapped in the lonely paths of the urbanized contemporary world. Heartbreaking paintings about solitude are found in the museums, and plenty of songs have been composed so as to make an allusion to the solitary souls. Respectively, cinema — through its prompt, profound, and pluralistic language—has broadly dealt with loneliness.

The films listed below may give rise to bitter feelings and call to mind that our mundane world is a world apart. Still, by sympathizing with the main characters and confronting meaningful grim experiences, eventually purification occupies the mind and soul.

15. Mystery Train (1989)

A young Japanese couple takes a train to Memphis. She seems somewhat moonstruck, whereas he overall is laconic and pensive. They both are rock ‘n’ roll enthusiasts, and so they travel from Japan to America in order to visit the cradle of Elvis Presley’s influential career. They hold a small vintage suitcase, longing for an inclusive cultural adventure.

The train’s doors open, revealing a vast silent ghost of a city. The couple wanders through the deserted streets, as if they could discover the ruins of a former glorious place, covered by the thick shadow of a drab present. Their way leads them to a local motel which —following the city’s exact motif — appears to be eerily empty and lifeless.

Yet, this motel becomes the intersection point of the couple’s brief story in Memphis with other two purposeful stories: an Italian woman who has nothing connecting her with this city or its cultural background stays overnight in this very motel, since her sole purpose is to receive her husband’s body. At the same time, a company of local outlaws takes action in a neighboring wretched room.

All of them have something in common and, at once, plenty of differences. The Japanese travelers crave being introduced to an era and sophistication which they have met in a distant, abstract, and charming way. The Italian lady visits Memphis by accident, whereas the local group of clumsy criminals represents a conventional contemporary lifestyle. Meanwhile, the city’s decayed character is expressed through the emblematic figure of Presley, who’s found in an old picture on the wall, or in a song played on the radio.

Jim Jarmusch elaborates on an underrated type of spiritual loneliness: the loneliness that is enforced on the ones who have discovered expressive means, emotions, and inspiration in a distant cultural space-time framework. Trains often seem to be magical, but they aren’t. They can travel in space but not in time, leaving some pieces of history intact, lying in their original setting, somewhere in the past.

Even though the main subject of the indie film “Mystery Train” is wistful, melancholic and multifaceted, Jarmusch synthesizes a highly entertaining filmic experience, originating from his unique and authentic personal style.

14. Ôdishon (1999)

The Japanese film “Ôdishon” could be a nightmare, a torturous subliminal manifestation of a man who has been confronted with losses of vital significance and long-term solitude. It’s a film that Marquis de Sade would have definitely enjoyed if he was born in our era. However, through its gloomy mood, extremity and disturbing appearance, “Ôdishon” exposes a commonly ignored realistic subject.

Shigeharu lost his wife long ago. Since then, he lives with his son, steeped in insecurity and emotional loneliness. Throughout these years, he developed a deep fear of interaction, progressively distancing himself from the idea of having a woman in his life. Accordingly, he is convinced by a friend to search for a potential bride at a fake film audition.

The loss of a domestic partner oftentimes spreads a subliminal sense of death. Additionally, the process of finding another mate looks like an audition, in which the interested person has to present an artificial or fragmentary aspect of their self. Approaching a person in order to make a brand new start after having shared a lifetime with a partner could feel like committing a kind of fraud.

In such a way, the film increasingly builds up a distressing ambience, foretelling a tragic happening. Shigeharu meets a younger woman and probably falls in love with her. Yet, he feels like a cheater and experiences an unrelenting emotional terror. The events that follow, through a dazzling engagement of conventional narrative and surrealism, represent Shigeharu’s mental disquiets and long-standing isolated spirit. What would a young and beautiful woman want from him after all these years? Perhaps there’s nothing more than death for him.

Although this film is not visually amiable to a great part of the audience due to its boldness and ultra-violent finale, it finds a place in this list, since it’s defined by artistic character, substantial thoughts, and creative intelligence.

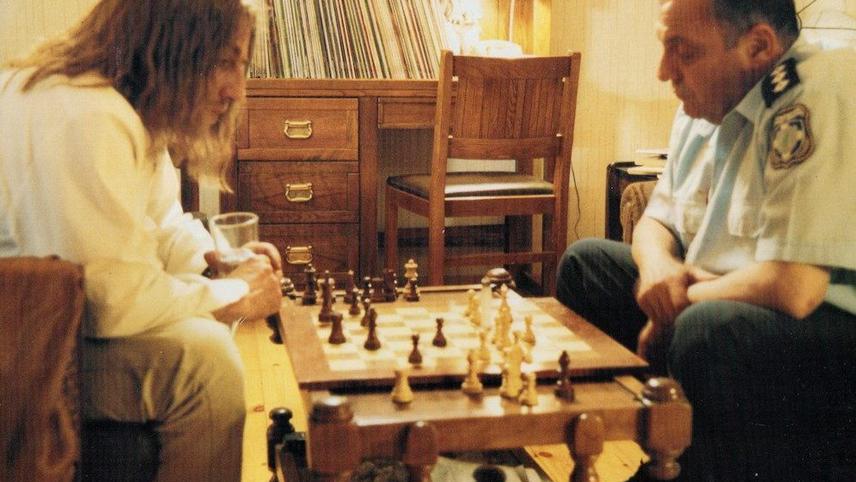

13. The King (2002)

A former drug-addicted dealer gets out of prison and decides to make a brand new start in his grandfather’s village, instead of heading back to his onetime lifestyle. After being victimized by the big city’s demons, Vangelis is determined to embrace a spiritually inclined way of living, occupying himself with constructions and creative hobbies.

Perhaps the pitfalls occurring in the urban centers aren’t found in the province, but the small societies suffer from countless maladies as well. Vangelis’ peaceful attitude couldn’t be more unwelcomed by the locals, who perceived his dissimilitude and discretion as an offense to their own conventional and socially reliant lives.

They methodically exclude him from every small-scale structure of their village, and eventually, it’s him against everyone. Only an outstanding policeman befriends the new unprotected inhabitant and vainly struggles to keep him intact from the beasts that mean to feed on his flesh.

Nikos Grammatikos’ film “The King” violently shakes a variety of rusty emotions and instincts through its sincere dramatic context, dealing with plenty of societal problems in their contemporary form. Essentially, Grammatikos demonstrates the ordinary people’s hostile attitude toward the ones who steer clear from self-exposure and purposefully choose to differ. This film honors those — commonly found between us — who are doomed to be flouted and confront a relentless social isolation.

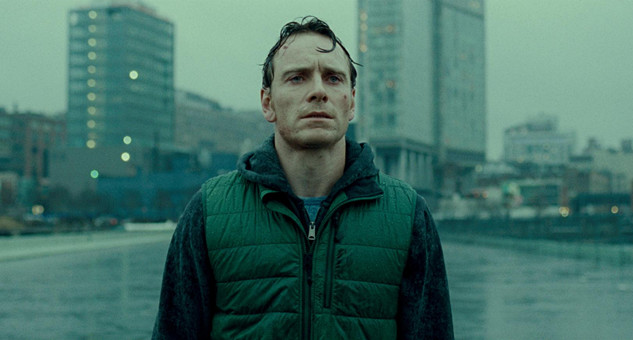

12. Shame (2011)

In Michael Fassbender’s imposing figure, a lot of ideas are personified. Inextricably linked to his unrepeatable leading performance in the film “Shame,” Fassbender embodies the entity of loneliness and self-destruction that is well hidden behind conventional job positions and decent clothing.

Brandon is a company executive in New York and lives alone in a luxury apartment. When the doors close, he drifts into a world of sultry overstimulation and extensive voyeuristic activity. Each in order, Brandon’s social attitude is dominated by an obscure dysfunction. In opposition to his overactive contact with prostitutes and involvement in meaningless sex with diverse partners, Bandon wavers to create sentimental bonds, revealing plenty of self-expression pathologies and communication disabilities.

His sister, Sissy, appears all of a sudden, shedding light on Brandon’s dark psychological profile. She’s sentimentally unsettled, desperately seeking attention and love through an uncontrolled and juvenile behavior. The siblings’ cohabitation is crucial, disclosing a primal disorder which restrains their relationship. They unwittingly hurt each other, since they are fundamentally drifted apart and suffer from deep insecurities, rejection, and existential loneliness.

Steve McQueen — more than shocking through the film’s noticeable explicitness — shocks through his work’s audacity, imperceptibly rising drama, and psychic overexposure. Both protagonists are lost in a maelstrom of alienation, depression and self-denial, torturously turning a blind eye on contact, profound pleasure, and love.

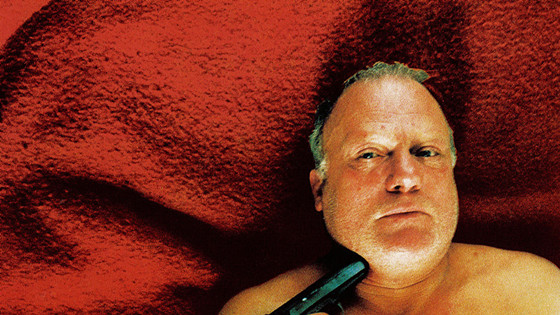

11. I Stand Alone (1998)

Evoking a stinging sense of pain that stays for long, Gaspar Noé’s “I Stand Alone” feels like a punch in the stomach. What is hidden behind an abusive man’s distorted expressive points of view? What kind of life fuels the forms of excessive violence which seem completely unreal and inhumane? Noé, through this bitter to the bone film, gives the answers.

This is the life of a butcher. His mother died after giving birth, while his father was punished for being a communist. He himself concisely narrates the story of his life, highlighting the tragic events that ravaged his soul and led him on a lonesome path of constant and vain fights against the system and social inequity. He was left alone by everyone, whereas he left behind a daughter when he served time in jail.

Henceforth, he is determined to start from scratch. But is he able to leave behind his wrecked soul and be someone else? He isn’t. An icy expression is indivisible from his face. Following the story through his thoughts, it becomes clear that he feels unspeakably aggrieved by everyone and offended by life itself. In this fashion, he offends every person and situation occurring in his way as well.

There’s only one person on earth who could ever love him: his daughter. He decides to meet her. He takes her to his gloomy hotel room, which reflects on his incommunicable misery. Should he die and take her with him? A man who has never been loved undeniably doesn’t know how to love and be loved. The film is deprived of any musical embellishments, leaving aside the scene in which he embraces his daughter and says, “Don’t leave me alone.”

10. The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter (1968)

There are many ways to be different, and accordingly, there are many forms of invented solitude. Based on Carson McCullers’ homonym novel, “The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter” proves that people — instead of accepting their internal and external dissimilarities— often choose to drift into the lair of loneliness and endure a restrained life in various ways.

Somewhere in the American South during the 1960s, daily suburban dramas sequentially intertwine, finding an intersection point in the effective presence of a deaf-mute man. Mr. Singer can’t talk, but he’s a great listener. He rents a room in a conventional family’s house in order to take care of his mentally ill friend. There, he bonds with the teenage girl of the house, who feels untended and lonely.

Apart from observing this small society’s structural cell from the inside, Mr. Singer plays a catalytic role for a local doctor’s life and mindset. Since he is an African-American man, Dr. Copeland admits only African-American patients. Moreover, it’s hard to accept that his daughter chose marriage over education against his will. Eventually, they both find out that the made-up disputes are completely insignificant and ineffective in life.

Through a simple, graphic, and essentially sincere synthesis of a traditional society’s portrait, this film focuses on the ones who refuse to come of age and simultaneously on the ones who are compelled to come of age prematurely. Nevertheless, as a gentle and comforting caress, “The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter” talks about those silent humans who are friends and guardians, even though nobody really looks after them.

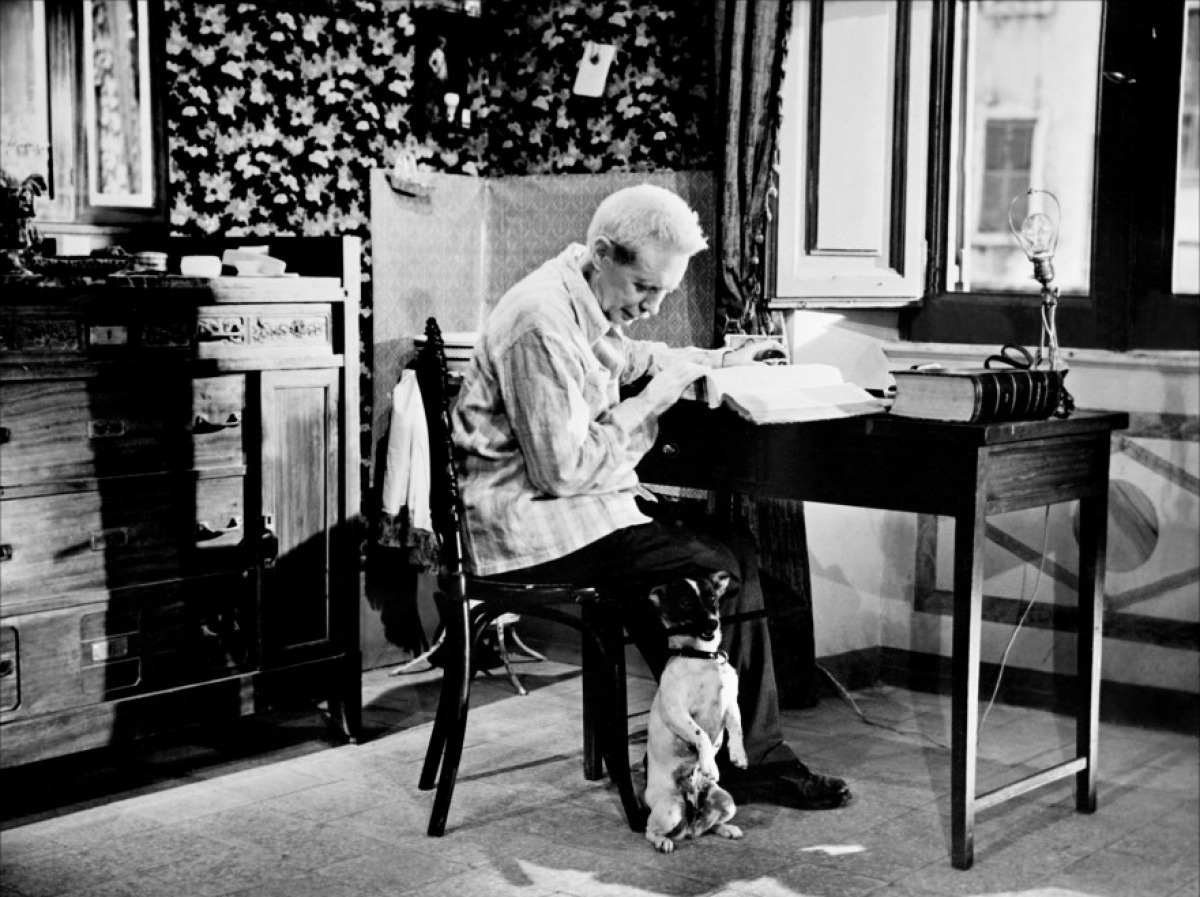

9. Umberto D. (1952)

Vittorio De Sica’s “Umberto D.” starts with a riot of retirees in postwar Italy. Umberto is one of them. He was once an esteemed civil servant who respectfully completed his years of duty. Nowadays, he’s found in a bleak room with the sole company of a tiny dog. His unyielding and quite profiteer landlord desires to expel him, while a young maid offers poor old Umberto a piece of kindness and sympathy.

On the sorrowful face of this solitary man, the ideas of loneliness and prospective death are captured. Despite this, Umberto attempts a battle against his definite finale. He seeks to find the money to keep his room, but even a shred of hope seems unachievable. He could ask financial help from his former co-workers, but they always are in a hurry to catch a shuttle bus. Eventually, he decides to panhandle, but the inner forces of his former pride stop him.

After all, he decides to die in his own way, vainly looking for a new home for his dog. Umberto approaches a speedily moving train, holding the small animal firmly, as if he could grasp a last chance of a fair life. Appearing as a momentous and beautiful postcard from the lands of solitude, the film “Umberto D.” is a hymn for the abandoned people who die all alone.