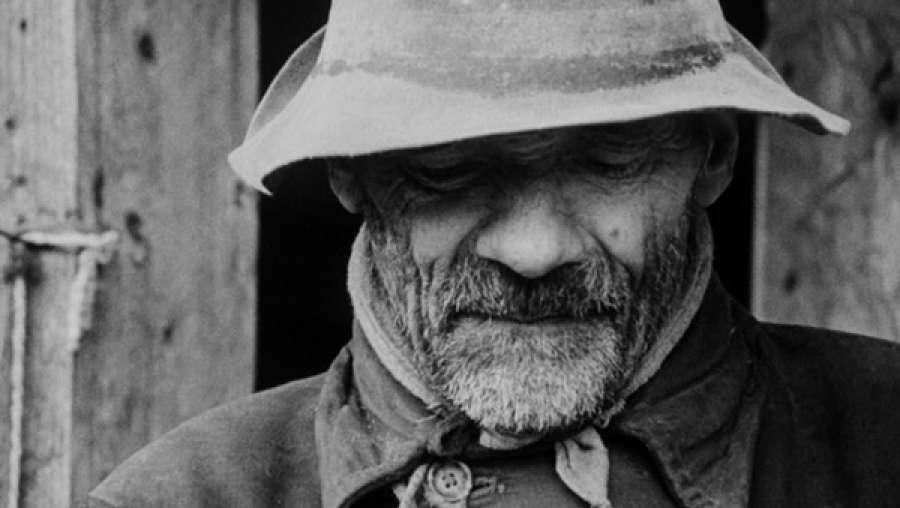

8. Pictures of the Old World (Dusan Hanák, 1972)

It’s testament to Dusan’s Hanák’s talent that his visual on the hard times endured by villagers in a remote Slovakian village is so life affirming. Their struggles with poverty and the march of time are not filmed to garner sympathy. On the contrary, the inhabitants’ happy-go-lucky attitude despite their meagre lifestyles is touching. Villagers are asked what is most important to them. Some say work on the farm, others believe good health, a few think it’s love.

This isn’t a Tarkovsky film: there are no great philosophical musings or attempts to grasp at a higher meaning to life. These are simple people with young and humorously self-deprecating minds that are at odds with their now old bodies. In one scene, a man takes a fall in town, remarking matter-of-factly, ‘‘I was strong and now I’ve had it.’ For these people, life goes on. There is something admirable and heartwarming about that.

7. Jacquot de Nantes (Agnès Varda, 1991)

Jacques Demy’s childhood as imagined by his wife, Agnès Varda, with snippets of Demy himself recalling crucial moments in his life that lead him from the mundanity of his father’s garage to his calling as a film director. Varda depicts, with great affection and a gorgeous mix of black-and-white and colour, his trips to puppet shows, his attempts at creating one of his own, the purchase of his first camera and holding small screenings of his crude short films for his parents.

It’s a biopic made with the sort of enthusiasm that could launch a thousand new film directors into the industry. Demy never lived to see the final results, but if the tenderness of Jacquot de Nantes is any indication, he certainly knew just how much his wife loved him.

6. Still Life (Sohrab Shahid-Saless, 1974)

Still Life centres around the isolated existence of Mohamad Sardari and his wife who live in a dilapidated shack that seems suspended in time. For decades, Mohamad has worked at a remote outpost, raising and lowering a gate at a track crossing as trains pass by a desolate landscape untouched by modernity, onward to civilisation. Mohamad’s world is turned upside down when his boss informs him that he is surplus to requirements.

As the title suggests, Still Life is a movie of inactivity; an inert lifestyle captured with static shots and dialogue so minimal it makes Tom Hardy’s role in Mad Max: Fury Road seem too talky. It’s astounding that one of the great Iranian films by one of the country’s greatest directors, winner of the Silver Bear award at the Berlin International Film Festival, is still so relatively underseen.

5. The Hunters (Theo Angelopoulos, 1977)

During a New Year’s Eve hunting party, a group of bourgeoisie socialites discover the frozen – and very much dead – body of a partisan fighter from the Civil War. They take it back to their vacation home and discover, to their horror and bewilderment, that the 30-year-old corpse is still bleeding.

Like The Travelling Players made two years prior, Theo Angelopoulos crafts The Hunters using set pieces filmed in graceful long takes, moving fluidly through time as past and present collide ambiguously. The complexity of the camerawork in these sequences (some of which surpass ten-minutes) at times bests even the Greek director’s four-hour epic.

Like many of his films, The Hunters is a difficult, opaque work of Greek history, but never anything less than an astonishing meditation on the ghosts of the past and how its scars may never heal, haunting in ways that cannot be fathomed.

4. The White Meadows (Mohammad Rasoulof, 2009)

Rahmat travels to various salt-covered islands in Iran on his creaky rowing boat, collecting the tears of its inhabitants. He has been doing this for three decades, the reasons a mystery to those who shed their sorrows into his glass jar.

Mohammad Rasoulof depicts each island’s ritualistic (and sometimes violent) behaviour with an honesty that never feels judgmental. The serene beauty of the film’s visuals clash with the brutality Rahmat encounters: one island sends a virgin girl out to marry the sea (to her death) in the hopes of rainfall; an artist who paints the ocean red is threatened with being blinded unless he disavows this artistic interpretation.

The White Meadows is a pointed critique of the Iranian leadership that got the Rasoulof and his editor – Jafar Panahi – prison sentences. As of now, neither can leave the country. Everyone involved in this modern masterpiece were willing to risk it all – it deserves to be seen by more people.

3. The Meetings of Anna (Chantal Akerman, 1978)

Anna is a film director who travels around Europe showcasing her work. Her life is a series of bland hotel rooms, strange cities observed only from her window and the fleeting interactions with other people who seem as lonely as her, such as an awkward sexual interaction cut short due to a lack of connection (or perhaps too real of a connection), or a chance meeting with a friend who insists that Anna marry her son and finally have children.

People seem drawn to Anna, confiding their innermost feelings to her as she listens quietly and indifferently. Indeed, it is only time spent with her mother that Anna begins to promise something more than listlessness.

Chantal Akerman’s long, fixed shots and peculiar framing imbues The Meetings of Anna with a mournful longing, a feeling of anxiety as to where the happiness of life can be found, if it even exists. Like Welles and Citizen Kane, it seems that Akerman’s body of work exists in the shadow of Jeanne Dielman. Even if she hadn’t made it, she’d still have The Meetings of Anna. Something most directors could only dream of.

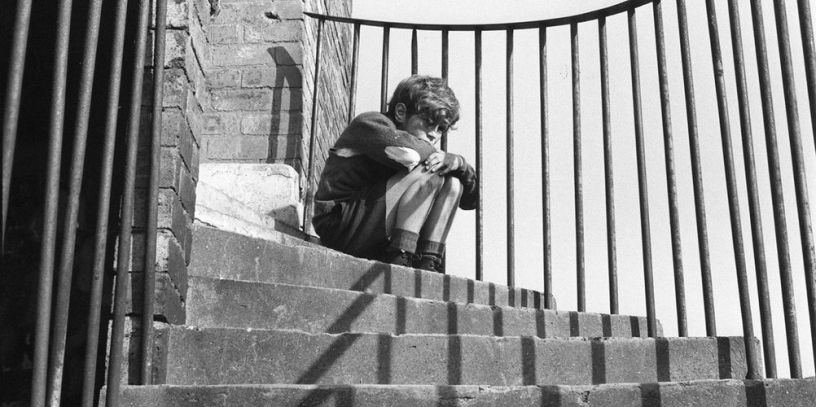

2. My Childhood (Bill Douglas, 1972)

When discussion turns to the quality of working class British filmmaking, the likes of Ken Loach, Terence Davies, Mike Leigh and Shane Meadows are rightly touted. Somewhere along the way Bill Douglas has been forgotten. My Childhood is the first part of what is known as The Bill Douglas Trilogy (My Ain Folk and My Way Home have even fewer votes on IMDb but are almost as good).

It traces Douglas’ upbringing in extreme poverty in 1940s Scotland, living with his brother and grandmother in a desolate mining village where dreams go to die in the pits. It seems improbable that a future film director could climb out of the endless hills made of coal, where much of the day is spent finding something to eat, or avoiding freezing to death by clasping onto mugs of hot water. Douglas portrays his childhood with despair but also great beauty. One of the underrated British masterpieces from one Britain’s greatest.

1. Du côté d’Orouët (Jacques Rozier, 1971)

Jacques Rozier’s Du côté d’Orouët feels like what might happen if Jacques Rivette and Éric Rohmer decided to collaborate with the objective being to create a film with the narrative looseness (and length) of the former combined with the whimsy and acute awareness of youth of the latter, but arguably surpassing anything in their respective filmographies. Du côté d’Orouët is a beguiling travelogue following three friends on vacation.

Caroline Cartier, Danièle Croisy and Françoise Guégan’s charming repartee and chemistry is so naturalistic, Du côté d’Orouët can sometimes be mistaken for a documentary in which Rozier is simply observing three lifelong mates hanging out.

It is atypical of French New Wave in many ways – Caroline, Joëlle and Kareen avoid wordy articulations of their own and each other’s feelings. They are propelled, instead, by instinct and an irresistible vitality. A joyous pilgrimage that stands alongside any of the best films of the movement.