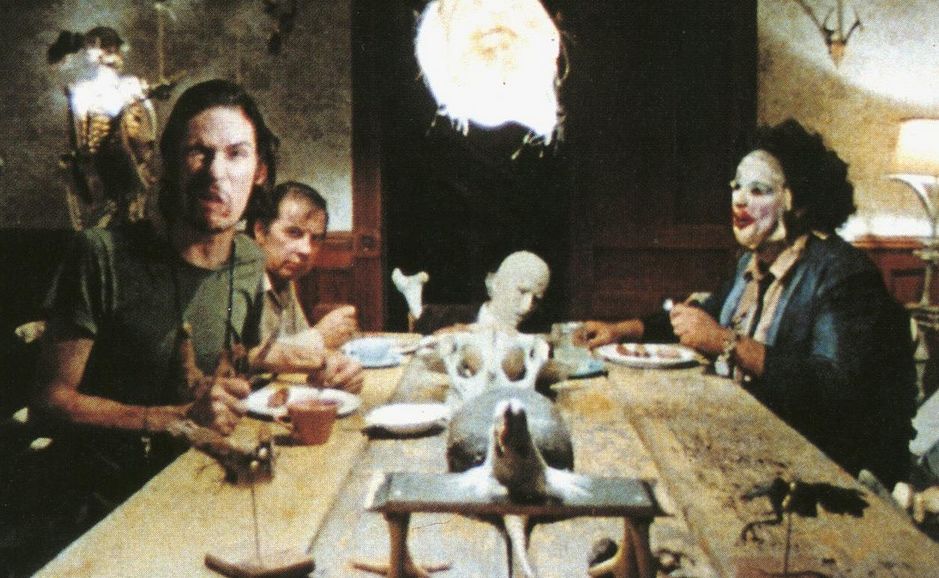

8. Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974)

Though the slasher film genre had already started in earnest with movies like Psycho, House of Wax, Peeping Tom and the nascent giallo genre, it was Texas Chainsaw Massacre that created the model for low-budget American slasher classics like Halloween, Friday the 13th and Nightmare on Elm Street.

Tobe Hooper’s incredible feat was realizing that he could actually use the low budget production values to his advantage. The at times grainy image and scratchy audio track gives the entire film the feel of a terrifying home movie about a family of cannibals. Adding to the feeling of realism is the opening crawl and the marketing campaign, which falsely presented the film as being based on real events– though the film is only loosely inspired by the murder spree of Ed Gein.

What often seems to get lost in conversations about Texas Chainsaw Massacre is that, like most brilliant horror films, it leaves most of the actual gore just off screen. In terms of the intensity of on-screen violence, it falls short of even the tamest contemporary PG-13 horror films– in fact, Tobe Hooper sought to get a PG rating for the film at the time.

Almost every aspiring horror filmmaker has learned and repeated the lessons of Texas Chainsaw Massacre. The Blair Witch Project and other found footage horror films of the aughts owe a special debt to Tobe Hooper in leveraging a low budget to absolutely terrifying effect, but filmmakers as diverse as Ridley Scott and Nicholas Winding Refn also credit the film as a major source of inspiration.

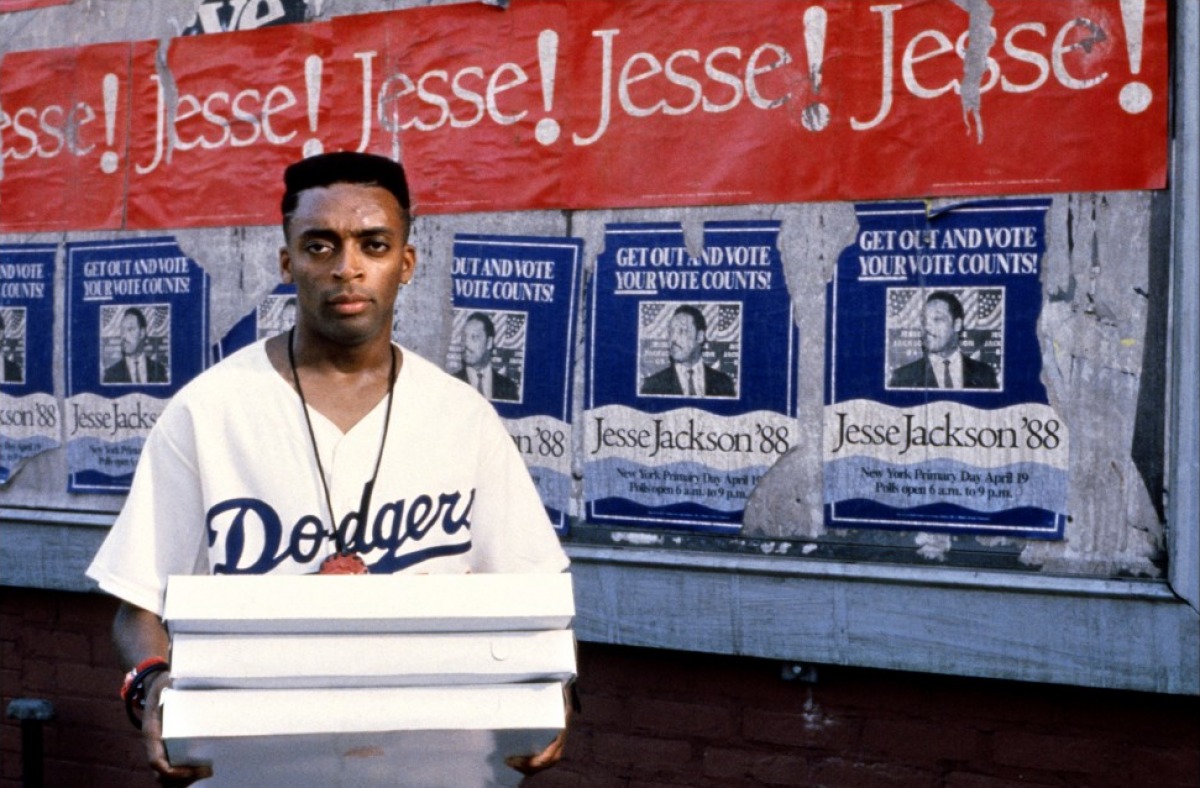

7. Do the Right Thing (1989)

Spike Lee made waves when he tackled issues of racism, civil rights and violence with Do the Right Thing. His film seemed prescient of the LA riots that followed the Rodney King beating, but feels even more relevant now with the rising awareness of police brutality against African-American communities, the death of Eric Garner– which has troubling parallels to Radio Raheem’s death –and the Black Lives Matter movement.

The film takes place on a block of Brooklyn’s predominantly black Bed-Stuy neighborhood and follows the brewing controversy around the local Italian-owned pizza shop– Sal’s Pizzeria. Despite his predominantly African-American clientele, Sal, played by Danny Aiello, refuses to put up pictures of black celebrities along with the Italian-Americans on his wall of fame.

As the controversy and tension escalates over the course of a hot summer day, Mookie, played by Spike Lee himself, finds himself caught in the middle of the great moral conundrum of the civil rights movement– between LOVE and HATE; Martin Luther King and Malcolm X; peaceful resistance and insurrection.

Do the Right Thing leaves the audience to come up with their own conclusions. It accurately portrays the dynamics of the neighborhood and the resulting consequences without ever defining “the right thing” of the title. The movie provided a huge point of inspiration for a whole generation of African-American filmmakers who now find themselves in the spotlight; filmmakers like Ryan Coogler, Ava Duvernay and Dee Rees. The film was brilliant when it came out in 1989 and its genius has only grown with time.

6. Reservoir Dogs (1992)

Tarantino’s trajectory from film store clerk to Cannes darling is the stuff of cinematic legend and it wouldn’t have been possible without the ingenuity and spunk of Reservoir Dogs. Frustrated by his inability to raise money for his other projects, Tarantino fashioned a nail-biting, taut and tense screenplay that could easily be executed on a shoestring budget, paving the way for the more well-realized indulgence of Pulp Fiction.

Reservoir Dogs is an homage to classic gangster heist movies, particularly the films of Jean Pierre Melville like Le Cercle Rouge, Le Doulos and Bob le flambeur. But, unlike those films, which dwell on the details of the plan and reach a climax during the heist, Tarantino flips the script by skipping the heist and focusing on the aftermath.

Tarantino’s work inspired a slew of (mostly terrible) ultraviolent gangster film imitators– movies like Boondock Saints and 3000 Miles to Graceland –but the biggest impact of his early films was to blow apart screenplay conventions and open the door for increasingly complex non-linear structures in masterpiece films like The Usual Suspects, Memento and Amores Perros.

5. Blue Velvet (1986)

Like all great filmmakers, David Lynch became an adjective used to describe other films and filmmakers. David Foster Wallace wrote a lengthy trying to get at just what it is that defines “Lynchian”. It’s hard to put a finger on just what it is about Lynch’s combination of the mundane and the bizarre that makes his work so unique. Blue Velvet marks Lynch’s first outing as a director working with a real budget from one of his own scripts and it’s still the clearest articulation of his unique cinematic fingerprint.

The film follows Jeffrey Beaumont, a clean-shaven kid played by Kyle McLaughlin, who finds a severed ear in a barren lot and becomes fixated on the mystery of who it belongs to and how it ended up there. Jeffrey’s obsession drags him into a depraved underworld where he’s seduced by lounge singer Dorothy Valens, played by Isabella Rosesllini, and takes on the responsibility of freeing her from the clutches of her sadistic tormentor Frank Booth– played by Dennis Hopper in his most iconic role.

Lynch’s film seduces and repulses in almost equal measure. It’s impossible to articulate precisely why Blue Velvet works as brilliantly as it does. It’s one of those films that you have to see to understand– which is what makes it a perfect piece of cinematic inspiration.

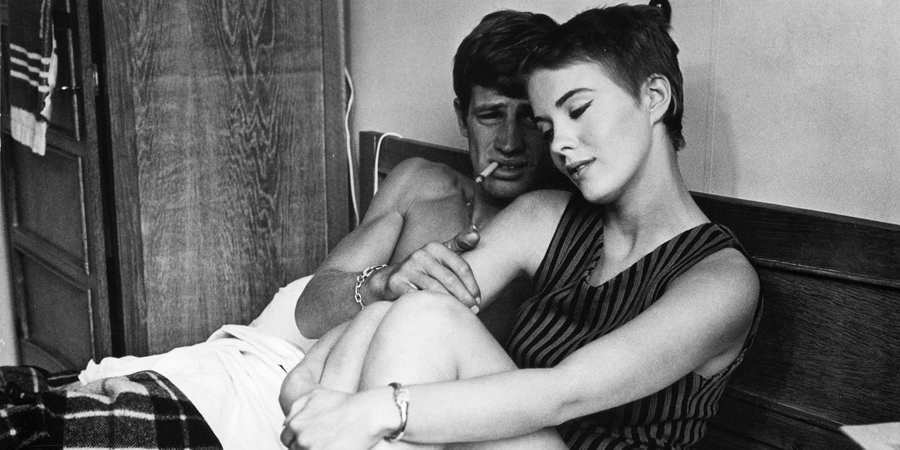

4. Breathless (1960)

The critics of the Cahiers du cinema invented the very idea of auteur filmmaking when they wrote about how directors like Nicholas Ray, Alfred Hitchcock and Jean Renoir used their cameras like a writer uses their pen. Not content with simply writing about film, the Cahiers critics famously took to the streets of Paris to put their theory into practice as they developed their own authorial voices to launch the nouvelle vague.

Jean Luc-Godard took a screen treatment from fellow critic-turned-filmmaker Truffaut and infused it with a combination of high art, poetry and American culture– jazz, big cars and Bogart –to create something truly unique that became the archetypal film of the French New Wave and the very essence of cool.

Jean Paul-Belmondo plays Michel, a hustler and small-time criminal who absentmindedly shoots a cop after stealing a car for a joy ride. After the crime, Michel returns to Paris to hide out with his lover Patricia, played by Jean Seberg, as he tries to convince her to run away with him to Italy.

Godard’s loose and playful approach to filmmaking and his disregard for traditional morality– expressed as guilt-free sex and guilt-free murder –was a huge breath of fresh air in the face of stolid moralizing studio productions. Breathless is also frequently credited with cinema’s first jump cut which Godard applied as a means of creating the film’s quick, syncopated pacing. Godard’s high-falutin ideas about filmmaking have fallen out of fashion and the films of his political period post-68 are rarely seen today, but Breathless is an undeniable masterpiece and continues to be a wellspring of inspiration.

3. Shadows (1959)

Shadows marks the directing debut of John Cassavetes, who would go on to leave a lasting impression on the future of cinema both as an actor, most known for his supporting turns in Rosemary’s Baby and The Dirty Dozen, and as a director of films like Faces, A Woman Under the Influence and Killing of a Chinese Bookie. Though his first film Shadows is one of his lesser known works, it was particularly influential as a watershed moment in American independent cinema.

The film follows a trio of mixed-race siblings of different skin tones played by Hugh Hurd, Ben Carruthers and Lelia Goldoni, moving through a Beat generation New York that has never been so clearly and beautifully represented on screen. Each sibling confronts their own dilemmas.

The oldest is a struggling jazz singer whose insistence on a slow-paced crooner style drives him to the fringes of the club circuit. The middle brother leads an aimless life, boozing about during the day and trying to pick up women at night while mooching off his older brother. Lelia, the youngest of the three, with skin light enough she can pass for white, loses her virginity to a charming young white man whose feelings for her change when he discovers she’s half black.

Cassavetes was far ahead of his time, not only with his subject matter, but also with his improvisational and collaborative approach to coaching actors. Shadows shows the results of that approach with the largely inexperienced cast turning in incredible performances. Cassavetes’ improvisational approach entered the filmmaking toolbook and proved a seminal influence on the New Hollywood generation of filmmakers, especially Martin Scorsese, for whom Cassavetes served as a mentor.

2. Bicycle Thieves (1948)

Forced to work with a small budget and non-actors after being rejected by the major Italian studios, Vittorio De Sica took inspiration from Charlie Chaplin’s lovable tramp to create the neo-realist masterpiece that is Bicycle Thieves.

The brilliance of the film comes from the simplicity and inherent pathos of its story. The protagonist, Antonio, finds himself a part of the mass of unemployed men in the economic crisis that swept post-war Italy. He finally finds a job as a sign-poster, but has to pawn off his bedsheets to buy the bicycle he needs for the job. On his first day at work, the bicycle is stolen and Antonio sets off with his young son to try and find the thief.

There have been a myriad of parodies and homages to the film– most recently Aziz Ansari’s Master of None and the Dardenne brothers’ The Kid with a Bike. The use of non-professional actors playing versions of themselves and the focus on working-class subjects have been widely influential to film movements around the world, from the fathers of the French New Wave, to third world cinema and British social realism. Its lasting impact can be seen in the work of contemporary auteurs like Ken Loach, Sean Baker and the Dardenne brothers who were all inspired by De Sica’s masterpiece.

1. Citizen Kane (1941)

Citizen Kane distinguishes itself from most other films on this list for being the product of a major Hollywood studio, the now defunct RKO. It makes use of every artifice in the Hollywood quiver of the time– expressionistic lighting, huge sets, matte paintings, forced perspective and special-effects makeup. With all of that in mind, it’s easy to forget that Citizen Kane was the work of then 24-year-old Orson Welles in his film debut as actor and director.

Citizen Kane follows the exploits of Charles Foster Kane, inspired by the real life William Randolph Hearst and played by Welles himself, who inherits a massive fortune and uses it to build a media empire, buying influence and power, but never quite attaining happiness. One of the film’s masterstrokes is its structure, which doles out the plot in the style of a detective film as an intrepid journalist sets out to piece together Kane’s life and uncover the meaning of the mogul’s legendary final word– “Rosebud.”

Citizen Kane moved the artform of cinema forward by leaps and bounds. It’s the great-grandfather of non-linear structure, it introduced the concept of deep-focus photography, overlapping dialogue and popularized the widespread use of wide-angle lenses. François Truffaut said that the film “has inspired more vocations to cinema throughout the world than any other.” It’s influence can be felt on films as diverse as The Godfather and Social Network and Peter Bogdanovich, director of The Last Picture Show and Paper Moon cites the film as the sole reason he set out to become a filmmaker.

Unquestionably ahead of its time, Citizen Kane flopped on its release in 1941 and hasn’t aged a day in the nearly eighty years since– it’s still the greatest film to inspire young filmmakers.