8. Yol (Yilmaz Güney – Palme d’Or 1982)

Tied with “Missing” comes “Yol,” the best-known work of proliferous Turkish director Yilmaz Güney. In most of his films, Güney portrays unknown aspects of the urban and country life of his vast country, in a period of political instability and repression. Apart from the state mechanisms, Güney turns his camera on the everyday reality of Turkish society, its customs, social hierarchies, and the relations between family.

In this particular film, the protagonists are three prisoners who are granted furlough to go visit their families:

Mehmet Salih has to face the contempt and disgrace of his in-laws for leaving his brother-in-law alone in a heist they had organized together. He will try to escape together with his wife, with no happy ending.

Omer is a Kurd, a political prisoner. Returning back to his village in the frontier of Syria, he will find the villagers in a fierce battle with Turkish soldiers. As his brother is shot dead during the battle, he has to take over his responsibilities.

Seyit Ali returns home only to find that his beloved wife has been working as a prostitute in his absence. Her family holds her captive and waits for Ali to come and end her life. Ali carries her on his shoulders in the snow, not having decided if he wants her dead or not.

A mosaic of pictures of remote corners of Turkey and unknown threats of Turkish life, depicted with realism and genuine emotion.

9. The Tin Drum (Volker Schlȍndorff – Palme d’Or 1979)

It could be called magic realism à l’aleman. Günter Grass’s novel was made into one of the most commercially successful German films of the 70s, and won the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film and the Palme d’Or (tied with Coppola’s “Apocalypse Now”). What was the movie about?

World War II, what else? The collective guilt of Germany once more on screen, this time through the allegory of a child who decided at age three not to grow up anymore. A grotesque figure that incarnates the impasses of European society in front of Nazism.

Oscar’s mother was conceived in a field in Poland, as his grandfather hid under the skirts of his grandmother evading from the authorities. He leaves her with Oscar’s mother in arms and flees to America.

This surrealistic start is followed by a story full of paradoxes – Oscar decides when not to grow up and he buys a tin drum, which he carries all his life. His voice is so shrill that it makes glasses break and Nazis dance merrily – love, anti-Nazi resistance and circus dwarfs, dispersed with deaths, mourning and a new beginning. At the end of the movie and World War II, Oscar decides to start growing up again, as society wakes up from nightmarish drowsiness.

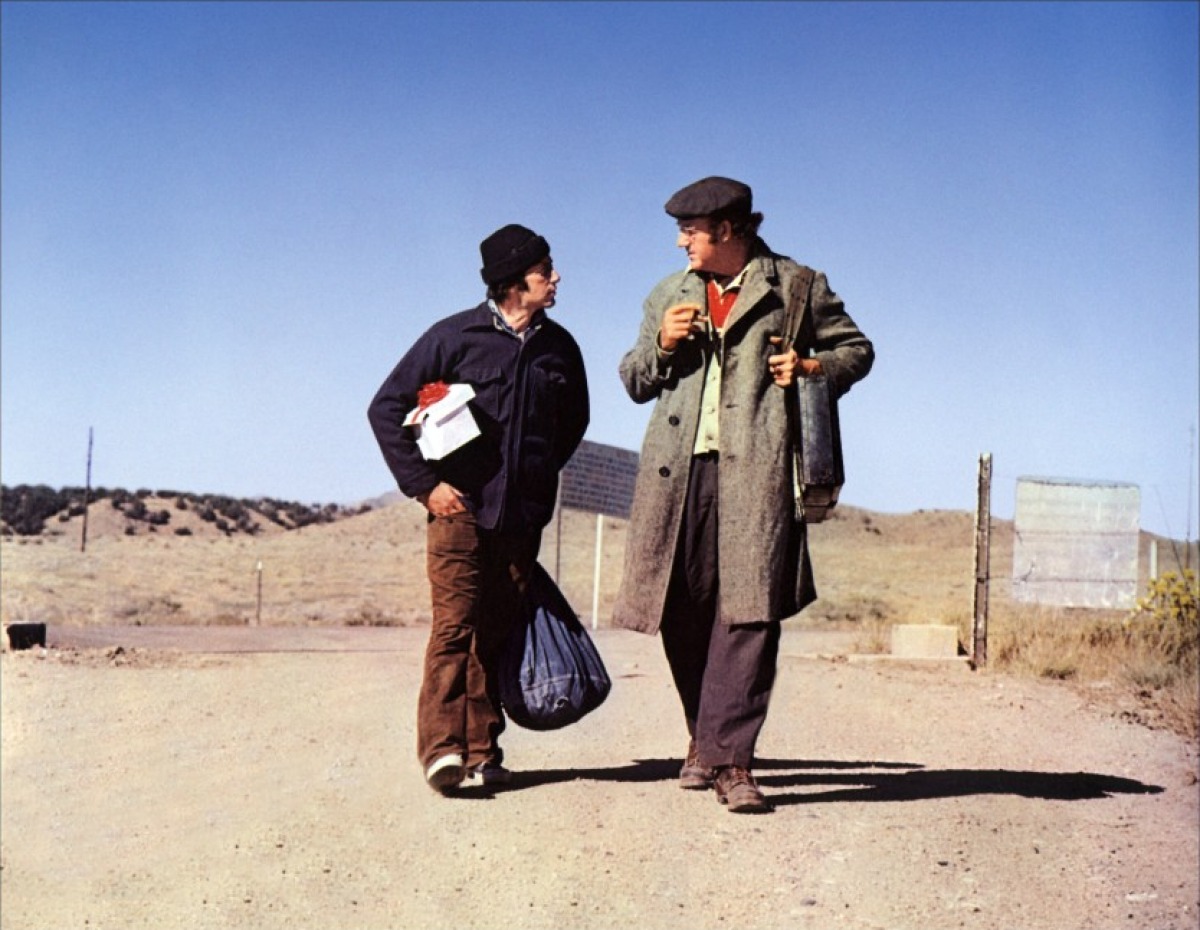

10. The Scarecrow (Jerry Schatzberg – Palme d’Or 1973)

This very distinct road movie, characteristic of the New Hollywood era, has many virtues, with its cast being the first and most important.

Just in between “The Godfather” and “Serpico,” Al Pacino gives an amazing performance on totally different grounds of the two mentioned above, proving he is an exceptional actor. He plays Lion, a homeless ex-sailor on the way to see his ex-wife and the five-year-old child he has never seen; who befriends Max, an ex-con who travels to Pennsylvania to get the money from his bank account and open a car washing station (Gene Hackman in an unforgettable role).

As road movies depend a lot on character building, this duo was an absolute success: the irritable and irrationally logical Max mates with credulous and sensitive Lion in an anti-hero minor adventure that definitely brings in mind the Oscar-winning “Midnight Cowboy.”

Along with the outcasts of the American dream, we see in the film a society that is changing, or the director wants to see it as such: the bars where our anti-heroes frequent play Motown hits. Even though they form a rather peculiar couple, they are welcomed almost everywhere and sometimes they all join in improvised Fellinian-type fiestas.

It is not society that presses on the heroes – rather, it is their sentimental impasses, all the things left unsolved that lead them to a dead end journey northeast, hitchhiking and jumping on trains, and trying to escape from their own pettiness.

11. Lulu the Tool (Elio Petri – Palme d’Or 1972)

The Cannes Film Festival supports political cinema, and this has been evident from the very beginning. In 1972, the Palme d’Or was awarded to two strongly political Italian dramas, “Il Caso Mattei” and “La Classe Operaia Va in Paradiso,” translated in English as “Lulu the Tool.”

This change in translation could mean a lot: the point leans on Lulu, the protagonist (Jean Maria Volonte, the protagonist in the other tied Palme d’Or winner), a chain worker in an Italian factory. He is divorced, is the leader of the factory’s union while he lives with a hairdresser and her son.

The leader works so hard as a model worker that when the night comes, he cannot even complete his erotic duties to his mate. Lulu knows his work devours him, leaving no space or time to enjoy life, but he is devoted to it, trying his best every day and ignoring the Sirens – young ultra-leftist groups of students who call the workers to rebel and strike against the patrons and the union leaders.

However, when his finger is cut by a machine due to the excessive demands of the managers for higher levels of production, his point of view changes. He befriends the students and leads a strike in front of the factory’s gates.

The Italian title goes much further: it is the very question of working conditions and the working class emancipation. If it is possible, how can it be achieved? What do the students have to do with the workers? All these questions raised by the social and political movements of the late 60s and 70s are addressed in this ambitious political manifesto that nonetheless is a bright cinematic masterpiece.

Elliptical, surrealistic scenes in the product line that Chaplin’s “Modern Times” would be proud of; Fellinian shots of a madman running to the door of the asylum crying “Strike! Strike!”; and excellent performances from all the actors and actresses who manage to combine vigor and humor. Though it treats a fundamental issue of modern societies that is basic in all revolutionary theories, the film is far from instructive, and this is his great advantage.

12. The Go-Between (Joseph Losey – Palme d’Or 1971)

Gifted with a screenplay written by no other than Harold Pinter and with music composed by Michel Legrand, this period drama emanates the nostalgic aura of the English countryside in the turn of the 19th century, and the life of the British aristocracy, which enchanting yet full of constrictions due to Victorian ethics.

It is the summer of 1900, the last summer of Queen Victoria’s life. Leo Colston finishes school and is invited by a wealthy classmate to his mansion in Norfolk. His friend Marcus gets sick with measles and is quarantined, and Leo befriends Marcus’ elder sister, the beautiful Marian who is engaged to Hugh, an estate owner of the region. Marion takes care of him, buys him a lovely green-velvet costume, and then sends him to carry messages between her and her lover, a neighbor farmer.

Leo passes his summer holidays and 13th birthday carrying the secret of the forbidden love between Marion and Ted, feeling guilty for betraying Hugh and the rest of the family. The end of this unforgettable summer will have unpredictable consequences.

The scenery, set in a beautiful corner of England, extenuates and appeases the feelings of the heroes. The young hero strolls around prairies full of flowers and groves of trees as a messenger who unites the two lovers, and the idyllic setting hosts the passion that staggers them and torments Leo, leading him to a very painful coming of age. Music, environment, acting, all of them form a magical cinematic experience.

13. If… (Lindsay Anderson – Palme d’Or 1969)

The students’ revolt around the globe in 1968, culminating with the months-long riots in Paris and other cities of Frances, definitely changed the social and cultural landscape of the world, especially Europe. As a result of the political unrest, the 1968 Cannes Film Festival was cancelled.

Next year, 1969, things were settled down and cineastes of all the world united in the Mediterranean city to celebrate one more big feast of cinema. In the aftermath of May 1968. And the Palme d’Or was given to the film that best expressed the 1968 stakes, Lindsay Anderson’s “If…”

Winning ahead of “Easy Rider,” the hippie road movie directed by Dennis Hopper, also a product of the same cultural change movement that shook the world, “If…” is far more political, an allegory that tries to explain what happened the months before.

Pupils return to a traditional public school for the new term, somewhere in Britain at the end of the 60s. Mick and his friends are a rebellious group of pupils who commit minor offenses throughout the year.

Once they’re punished by having to clean a storehouse, they discover a caché of automatic weapons and mortars. The day the parents are visiting the school, they start an armed rebellion against everything that stands in their way.

Far from the peaceful demonstrations that filled the boulevards of the French capital, Anderson takes the confrontation with the established authority to its limits: the fight for freedom and emancipation is a fight between life or death.

14. Black Orpheus (Marcel Camus – Palme d’Or 1959)

A beautiful Franco–Brazilian movie set in Rio de Janeiro during Carnival, reviving the ancient Greek myth of Orfeo and Eurydice, a vivid and colorful film with a beautified, festive look on the favelas’ reality, a film full of bossa nova and dance, full of carnival.

For reasons I do not know, ancient Greek names are very common in Brazil, among people of all social strata. So it is no rare that an Orfeu, the driver of a trolley bus in Rio, meets Eurydice, a young girl who rushes to Rio from the countryside, believing that someone is after her, wanting to kill her.

As Eurydice’s aunt, Serafina, lives next to Orfeu, the two youths meet again and it doesn’t take long until they fall in love, to the despair of Mina, Orfeu’s fiancé who was planning to marry him soon.

As the residents of the favela (slum) prepare themselves for the big Carnival parade, a mysterious man dressed as Death appears looking for Eurydice. As she is trying to escape both from him and the enraged Mina, carried away by Carnival’s whirlpool, she moves toward her tragic end.

When the recipe is good and simple, you get a good movie. Exotic settings, a celestial soundtrack by Luiz Bonfa and Antonio Carlos Jobim, lovely and exquisite amateurs as protagonists, love’s magic, Carnival’s frenzy – all those together made a film that is now considered as a classic and justified Marcel Camus’ risky decision to go down to Rio and film it, sleeping on a beach to spare the costs of a hotel as he had a very tight budget.

15. Jigokumon (Teinosuke Kinugasa – Palme d’Or 1954)

The first Palme d’Or for Japan, “Jigokumon” was the first color film to be released out of the country and win awards in both Cannes and Hollywood. It was visually stunning to watch all those samurai in their multicolored, printed clothing walk along the screen in groups of three or four, or fight each other in the in Heiji rebellion in the very beginning of the movie.

Japanese cinema might have been very strange for Western eyes – but no less fascinating. What in Hollywood would be considered as the culmination of a movie – a fierce battle between rebels and those loyal to the king samurai – is the opening scene that leaves the audience stupefied by its ferocity and vividness. But it’s with the depth of the feelings that actually captures us.

Loyal samurai Moritoh Enda escorts the court lady Kesa, who poses as his lord’s sister to create a diversion while the lord’s sister flees in the midst of people. He saves her when attacked and he deeply falls for her.

When Lord Kiyomon’s power is restored, he wants to reward his faithful samurai by fulfilling their wishes. Moritoh asks lady Kesa to be his wife, only to learn that Kesa is already married to samurai Wataru from the imperial guard.

Monitoh is blinded by his passion for Kesa and loses any sense of morality in order to get her, even against her will. He acts in a selfish, careless way that leads the story to a tragic end.

The Japanese way of depicting a deep erotic drama is rather schematic: even though Monitoh’s senseless passion is portrayed in an exaggerated way, the calm and confident love of Wataru for his wife and her love, loyalty and fear are shown, rather insinuated to us through subtle body and eye moves, letting the full moon speak the words of devotion.

A well-hidden jewel of Japanese cinema, released both by “Masters of Cinema” and the “Criterion Collection.”

Author Bio: Regina Zervou is cultural sociologist who took some fifteen years to move from carnival and popular culture studies to cinema theory. An afficionado of movies since she was twelve, she loves the way reality and ‘surreality’ is depicted on the screen. When not watching movies, she loves walking the dogs, swimming, cooking for her children or traveling someplace in Africa or South America to take some pictures.