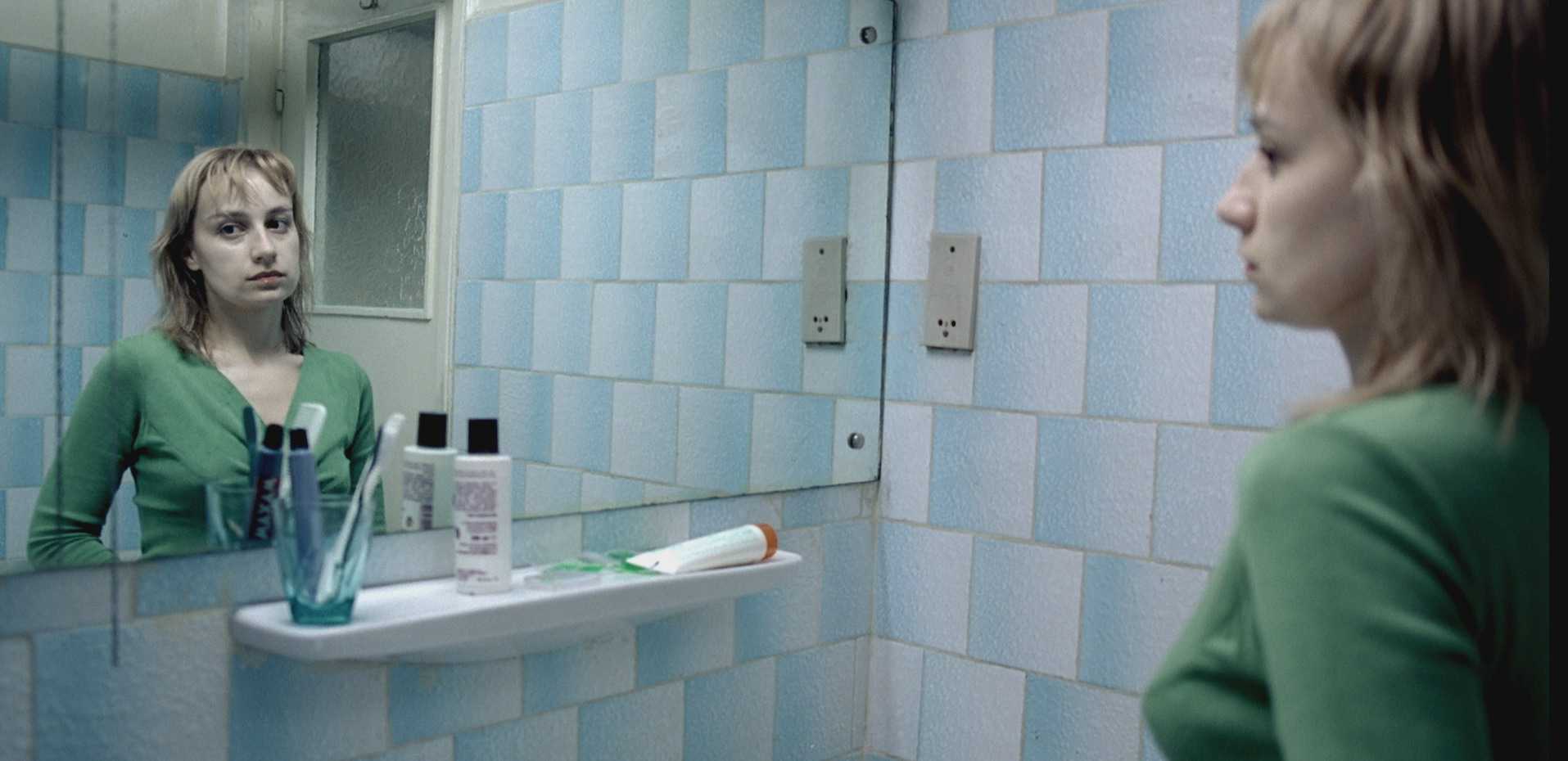

7. 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days (2007)

Throughout the limited timespan of a 24-hour period, Otilia, an assertive university student helps her absent-minded roommate have an illegal abortion, experiencing unprecedented belittlement and terror. More significantly, however, Otilia comes up against with society’s oddities, solid ego, and lack of compassion. Even if in this story all of the enmeshed parameters and characters appear to be disappointing and hopeless, Otilia herself is a youthful and charmingly foolish breath of hope.

Otilia and Gabriela have secretly arranged the illegal operation with a proposed black marketeer, who, as a result, takes advantage of the desperate women for the sake of redemption. Since Gabriela is a hesitant and flaccid girl, Otilia does all the hard work, hoping for the best. The outcome of their adventure, however, involves uncomfortable and unexpectedly defining moments for both of them.

Although intense emotionally charged moments are diffused throughout the movie’s length, the emotional heights reach a peak when Otilia attends a pretentious dinner at her boyfriend’s home. She rashly leaves her friend at the hotel, so as to keep her boyfriend’s mother satisfied with her presence. At the dinner table, she is confronted with the low middle-class banqueters who don’t hesitate to expose their overrated and elitist perceptions. Considering Otilia’s ghastly background and overworked mind, this setting effectuates a lasting and deeply disturbing sentimental involvement.

6. The Circle (2000)

In the beginning of Jafar Panahi’s “Dayereh,” Solmaz Gholami is a woman whose name is called in a hospital. Several years later, cinematically depicted at the film’s finale, the same woman’s name is similarly called in a prison. The film leaves this woman out of its story, since it doesn’t matter who she is anyway; she’s just another woman born in Iran, fighting throughout her lifetime with the same demons, as her mother and her unwelcomed daughter did.

As it seems, this film is about women. Female citizens define a social subgroup that is equally treated by the Iranian patriarchy, even to this day. Along these lines, nine women endure parallel oppressed lives in Tehran from the presence. Each of them represents a different stage of a woman’s life, which is always restrained by the same parameters, unexplainably and maddeningly. This circle (the English translation of the film’s title) of a depressing societal oddity opens and closes with the same female name, expressing the undeserved repetitiveness of a humanely foregone living.

“Dayereh” was banned in Iran, while Panahi was sentenced to a 20-year abstention from his occupation. This third feature film from Panahi,, through its symbolism, contextual strength and troubled wider social framework, stirs an unrepeated sentimental awe.

5. La Strada (1954)

Why do people really need clowns and circuses? Drawn expressions of happiness, vivid colors, and unrestricted motions have been imported so as to conceal reality’s faded tone, misery, and sultry restrains. But the people behind these fake expressions, insincerely glowing shades, and joyful performances aren’t sentimentally bounded by their occupation’s appearance.

Gelsomina, the sad protagonist of “La Strada,” whose mentality is found somewhere in between lunacy and naivety, was sold by her mother to a shallow-minded street performer. During her short road journey with Zampano, Gelsomina seeks an existential purpose, grasps every moment of humble sentimental satisfaction, and mainly, chases after the unknown emotions of love and tenderness.

Zampano, however, appears to be completely indifferent about Gelsomina’s emotional needs. He bought her in order to benefit from her services, returning to this abandoned and defenseless child a minimum profit.

A short coexistence of these radically dissimilar souls tears them apart day after day. He carries out the same performance every single time, breaking with his chest a chain made of cast iron. She more and more gets injured by his ignorance, mistreatment and baneful carelessness. Eventually, their paths separate.

Seeing Gelsomina’s deeply sad eyes, dishearteningly hiding behind clown makeup, is enough to make you remember her forever. She’s a doomed soul that never found happiness; she was never meant to belong somewhere or to someone. Zampano learned after several years that she died due to a terminal illness, and moreover, she used to play a sad song on the trumpet until the end of her days. Out of the blue, it seems like this man of iron isn’t truly unbreakable; if Gelsomina is gone, he’s really alone.

4. Come and See (1985)

Children of the past and the present commonly play “war.” Hiding behind plants and searching for buried weapons in the sand, a group of children enrages a man who has become aware of their macabre game. One of these children, Florya, would soon behold the bloody and grimy war of the adults, feeling its unspeakable turpitude in his bones.

It’s 1943 in Belarus, and Florya perhaps thinks that fighting against German soldiers could be somewhat more fascinating than playing with his friends. Thus, he lightheartedly takes an old weapon and joins his country’s armed forces. Yet, the unit decides to leave him back due to his young age. In the forest, he meets Glasha, a teenage girl with whom he spends a lot of time. The monster of war radiates a smell of sickness and death all over, but Florya and Glasha don’t constantly sense it. Their intact minds subtly explore each other, and their youthful bodies dance in the rain.

Florya decides to visit his family with Glasha. Entering his house, a horrid mess of a recent invasion isn’t enough for him to intuit what his innocent yet eyes would erelong see. Going across a muddy area, he finds his body completely sunken in the mud. Setting his foot on the other side, there’s no way to go back. His mother and two sisters are dead. He doesn’t see them, but he knows it. The Nazis have killed the entire village and now they burn horrid piles of soulless bodies.

The face of a child transfigures to an old man’s long-suffering physical appearance. Elem Klimov’s “Come and See,” with enthralling performances that speak to the heart, methodic camera work, and a storming ambience, depicts the rotten nature of war, its corporeal depravity, and mostly its inhumane and degenerative impact on mentality. War, as the seediest human condition, grays a soul’s innocent feelings and converts them into a once-and-for-all sentimental burnout.

3. The Cow (1969)

From the first days of recorded history until this current era, and from the West to the Deep East, the concept of owning treasures, even acclaiming their indivisible value in life always existed. In a small village of Iran in the 1960s, even earlier or even much later, a single cow could be for many people a precious gift by Mother Nature for facing a specified and geographically limited life.

Dariush Mehrjui’s characters, illustrated in his film “The Cow,” live significantly simple lives. Being born and dying in their consistent and barren village, these realistically portrayed countrymen don’t occupy themselves with much more than worrying about the inhabitants of a neighboring village, who are supposed to steal their necessary animals at night.

Hassan loves his cow dearly. A humble creature staying in a stable next to the house offers Hassan practically nothing more than some primary goods. Through Hassan’s primal cerebral diodes, yet, his beloved cow transcendentally implants in his heart a scope for his days and an outstanding identity. Accordingly, he’s more than devastated after finding out that his cow is gone forever.

So easily and so uncannily, a common healthy man becomes a tragic hero. It seems like he can’t stand being himself without his cow, since this animal used to make him differ from the rest countrymen; this animal used to be his one and only treasure. One day, Hassan is carried by his friends, restrained with a rope. Still, his ravaged mind and soul couldn’t be controlled by anyone.

2. Leviathan (2014)

Kolya has earned his respectable property with sweat and toil. A lifetime’s hard work allowed him to enjoy a secure home with a view of the seashore. Howbeit, defying this decent man’s long-standing efforts and acclaimed rights upon his land, a domineering local lord intends to demolish his house and seize on his grounds as well. Even if Kolya’s dominance is supported by common sense and humanist justice, an outraged battle against the fabricated jurisdiction of the ruling power seems to be in vain.

Fluidly, somehow absently but severely, the film’s structure and pragmatic performances steer the viewer toward Kolya’s unfeigned emotional storm. His family is violently removed from their home, but nothing is possible to hamper the merciless human forces from disturbing their lives’ serenity. These forces vitally deride Kolya’s dignity and existential importance. In our depressing and declining reality, Kolya could be your neighbor, your friend, or even you.

“Leviathan,” emerging from Andrey Zvyagintsev’s artistic originality and perhaps resembling Bela Tarr’s terrifyingly sleepless cinematic lands, formidably stands for the beaten and the damned of our undying injustice and criminal apathy. Through its underlying and at once sweeping tense, this piece leads to a sentimental climax of despair, compassion, and a commitment to the story’s misused struggling.

In the homonym myth, God Hadan manages to defeat Leviathan, a terrible sea monster. But where is our omnipotent God when the terrible monster of tyranny rages, vanquishing the weak ones occurring in its way? Even if a sea of justice strikes the rocks of inequity with its furious waves, millions of years have to come and go through in order to erode the solid rock formations…

1. The Virgin Spring (1960)

A father discovers that his beloved only daughter was brutally raped and murdered by three strangers for whom he lavishly offered a place to recline and some food to satisfy their hunger. How would a man in such an unutterable emotional situation react? In one of the most beautiful, haunting and overpowering scenes of cinematic history, Max von Sydow crossly calls to arms all of his physical strength, attempting to vent his great anger by bending a tall tree, as if he could defeat life’s callosity.

Ingmar Bergman’s “The Virgin Spring” isn’t barren of contextual complexity, boldness and artistic value in relation to his most popular masterpieces. In his personal intelligent way of engaging the spectators in religious topics, Bergman promptly evokes deep questionings and philosophical introspections, before even a slightly transparent idea of resisting to this mental procedure is born.

This all-time great piece of the seventh art elaborates on the moral values and exhaustions that are conventionally attached to religion. Showcasing an allegorical dramatic story of losses, envy, and violations, “The Virgin Spring” proves that ethics exist even without religion.

The people of the 14th century were tough in that being caring and decent means not only to being able to accept and forgive, but bear and suffer as well. How does this condition reply to reality and its tragedy? Humans are meant to lose everything but their emotions. What makes you a human, more than anything else, is your deep, varied and undimmed emotional world.