7. The Witches (1990)

Roeg’s wildly imaginative and unabashedly odd adaptation of Roald Dahl’s 1983 children’s novel “The Witches” ushered in the 1990s with a dark and delectable fantasy.

Ably assisted by Jim Henson’s Creature Shop (Henson was also a producer, and unfortunately he and Roeg regularly disagreed with one another during the production), and a wonderfully OTT Anjelica Huston, The Witches tells the tale of 9-year-old Luke Eveshim (Jasen Fisher), who is staying at a resort with his recuperating grandmother Helga in Norway (Mai Zetterling).

His idle is ruined by other guests at the hotel, the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children, led by one Miss Ernst (Huston) who also goes by the secret sobriquet of Grand High Witch. Luke is certain this society, secretly a witches coven, has a fondness for transforming children into mice.

The freakish fun of the Witches, which also zigzags into creepier waters at times, is also improved upon by Rowan Atkinson’s put upon hotel manager, Mr. Stringer. For inventive and ambitious fantasy for all ages, Roeg’s The Witches delivers. Perhaps the only real caveat here, and it’s one that ruffled Dahl’s feathers more than anyone else, is that it has a much more upbeat ending than the decidedly darker source material.

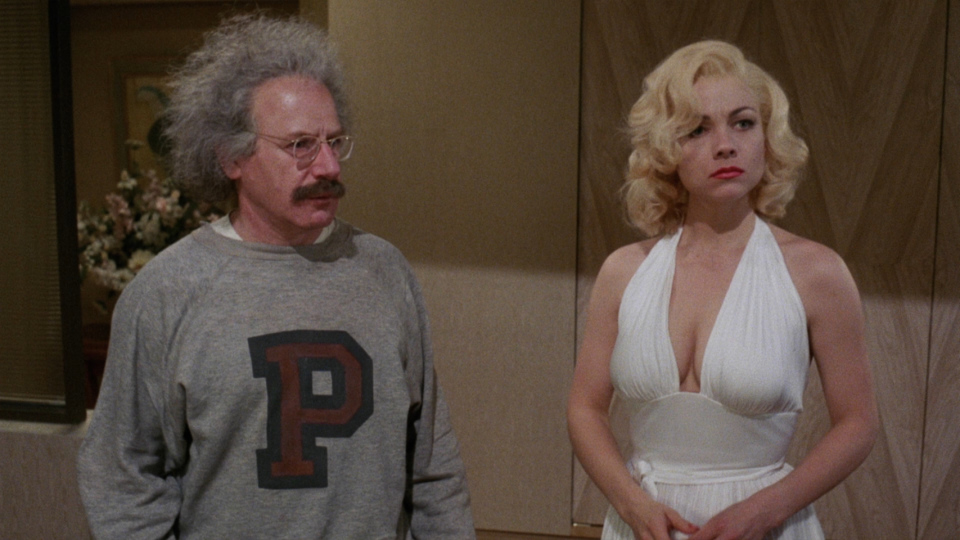

6. Insignificance (1985)

Adapted from Terry Johnson’s play, Roeg’s film occurs on a summer night in 1954, set in anonymous hotel rooms where the lives of four iconic figures; Marilyn Monroe (Theresa Russell), Albert Einstein (Michael Emil), Joe DiMaggio (Gary Busey) and Joe McCarthy (Tony Curtis) – though in the film they are simply and slyly referred to as the Actress, the Professor, the Ballplayer, and the Senator – fatefully intersect.

These recognizable popular culture figures, in typical Roeg fashion, riff on grandiose ideas and floundering emotions. What begins as trivial digressions gains momentum and significance, buoyed by stellar performances (like Curtis’s McCarthy, witch-hunting endlessly in his mind, or Russell’s Monroe, who, despite her ditzy dilettante routine can still teach Einstein a thing or two about relativity).

On the surface Insignificance may not be the exacting pedigree of Roeg’s recognized masterpieces, but it’s still a vast, ingenious allegory on fame, life, love, obsession, jealousy, and substantially so much more.

5. Eureka (1984)

Another of Roeg’s films to be unjustly ignored upon release, “Eureka was very bad timing,” he explains. “It was the early 1980s: Reagan and Thatcher were in, greed was good, and here was a film about the richest man in the world who still couldn’t be happy. Politically and sociologically, it was out of step.”

Inspired by compelling true events, Eureka tells the story of a Klondike prospector who hits it rich, the fictional Jack McCann (Gene Hackman), based off of Sir Harry Oakes, who was murdered in the Bahamas, on an island he owned back in 1943.

In Roeg’s film, Jack’s tale jumps back in forth through his life, and we find his dynasty from the gold rush put in jeopardy as his adult daughter Tracy (Theresa Russell) and her husband Claude (Rutger Hauer) scheme away to usurp his fortune, even his soul.

Simultaneously to this almost Shakespearean betrayal are a pair of greedy, mob-tied investors Mayakofsky (Joe Pesci) and Aurelio D’Amato (Mickey Rourke), but even they seem subdued compared to JAck’s own inner demons.

Director John Boorman (Deliverance [1972]) famously described Eureka as “the best picture ever made — for an hour”, and Danny Boyle (Trainspotting [1996]) recounted how inspiring he found the film; “There was a couple of scenes [in Eureka] in particular, a death scene, and a kind of orgy, and I remember I just felt completely breathless, just unable to catch a breath at all… It’s not a bad thing to aim for.”

As beautiful, bizarro, and byzantine as Roeg’s finest films, Eureka is a film in need of a reappraisal. “One of the richest movie labyrinths since Citizen Kane,” writes Film Comment’s Harlan Kennedy, and he’s not at all wrong. It’s another dizzying tour de force, and perhaps an unexpected one. “What Roeg brings to the party is a flair for the sensational,” enthused Roger Ebert, “for characters who are larger than their weaknesses, who are connected to great archetypal forces.”

4. Performance (1970)

Roeg’s directorial debut (co-directed with Donald Cammell) was a product of the psychedelic and very Swinging Sixties. Produced in ‘68, Performance didn’t get released until 1970 as Warner Brothers was cold footed to release a film with such graphic violence and strong sexual content.

Today viewed as the quintessential cult film, Performance is all hallucinations and psychologically complex melodramatics, geniusly shot and edited into a compelling and complex mosaic.

Also contained within its paranoia-addled mainframe is a zero cool British gangster template (a huge influence on the crime films of Guy Ritchie and Quentin Tarantino, amongst others), and one of the most influential and imitated soundtracks of that era (Ry Cooder’s slide guitar gets mad props).

The film stars James Fox as a violent, hair-trigger hitman from London named Chas. In a serious jam, Chas tracks down the semi-reclusive rock star Turner (Mick Jagger, in his film-acting debut), looking for a place to hideout.

Turner lives with two smokin’ hot scenester companions, Pherber (Anita Pallenberg) and Lucy (Michele Breton), and though Chas and Turner initially clash, their mutual fascination with one another, combined with their drug-enhanced psychological sparring results in a stunning blur of assimilation, self-loss, and identity thievary. Sensational strangeness abounds in this phenomenal mindfuck of a film.

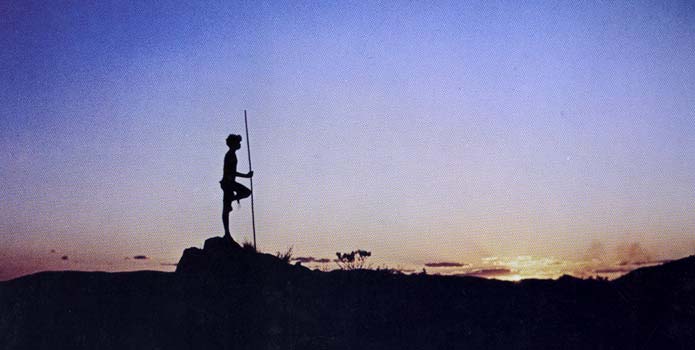

3. Walkabout (1971)

“A meditation about living on earth, which finds beauty in the way mankind’s intelligence can adapt to harsh conditions while civilization just tries to wall them off or pave them over,” praised Roger Ebert, who wrote about the film many times, accurately and enthusiastically proclaiming that “Walkabout is one of the great films.”

Powerful visual compositions with an almost religious intensity permeates Roeg’s meditative, haunting, and at times eerily surreal story of survival in the Australian outback. Using James Vance Marshall’s 1959 novel “The Children” as a starting point, Roeg’s story involves a teenage girl (Jenny Agutter) and her little brother (Luc Roeg, the director’s son), who are left stranded in the wild after their father (John Meillon) suffers a breakdown and attempts to murder them before his own horrific suicide.

Aided by an Aboriginal boy (David Gulpilil) on his titular rite of passage journey, and Roeg’s exuberant visual dynamism, Walkabout is an exotic, inspiring, and absolutely unforgettable arthouse entry.

“One of the most original and provocative films of the 1970s,” wrote The Movie Guide’s James Monaco, adding that “Walkabout is set in terrain stranger and more awe-inspiring than that of any science fiction film.”

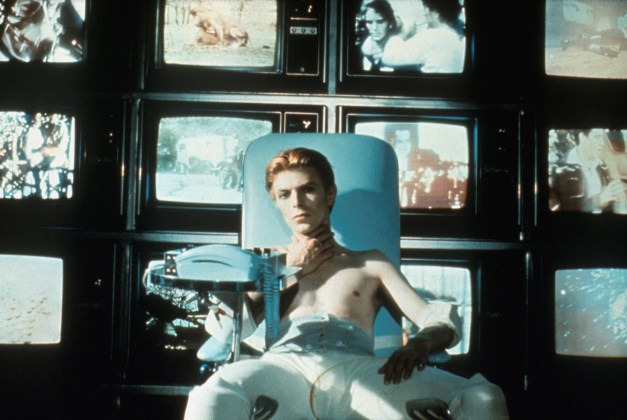

2. The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976)

With an abundance of unexplained skips in location and chronology and his cheeky trademark sophisticated style, Roeg’s adaptation of the 1963 Walter Tevis novel, “The Man Who Fell to Earth” is an ambitious and meditative marvel that was, of course, quite ahead of its time.

Described by Time Out as “the most intellectually provocative genre film of the 1970s,” and starring Thin White Duke-era rock icon David Bowie as Thomas Jerome Newton, an alien who’s doomed visit to Earth offers up a multifaceted and ultra-sophisticated inspection of American culture, heartbreak, and homesickness.

The film struck a chord with niche audiences, rendering it cult status pretty quickly (prolific sci-fi author Philip K. Dick became particularly smitten with the film, incorporating elements of it and of Bowie’s iconic eminence into his must-read 1981 masterpiece “VALIS”).

Bowie’s character is named for the English scientist Isaac Newton, discoverer of gravity, and as our protagonist in this mind-bending SF masterpiece, he makes discoveries as philosophically and psychologically substantial.

“The story unfolds in a daring sequence of narrative leaps,” writes The Guardian film critic Peter Bradshaw in his glowing five star review, adding that the film is “a freaky, compelling concept album of a film.”

Poignant, provocative, and deeply transfixing, genre films are rarely as meaningful, extravagant, or as ambitious as The Man Who Fell to Earth. Populist cinema this most certainly is not (when was Roeg, wearing his director’s hat, ever mainstream?), and though at times perhaps indecipherable, Roeg is a satirist and an artist of incredible breadth of view. When was sci-fi ever this iconoclastic and cool?

1. Don’t Look Now (1973)

“[Don’t Look Now] remains one of the great horror masterpieces, working not with fright, which is easy, but with dread, grief and apprehension,” writes Roger Ebert, adding that “few films so successfully put us inside the mind of a man who is trying to reason his way free from mounting terror.

Roeg and his editor, Graeme Clifford, cut from one unsettling image to another. The movie is fragmented in its visual style, accumulating images that add up to a final bloody moment of truth.”

After their daughter’s tragic death by drowning, grieving parents John and Laura (Donald Sutherland and Julie Christie) retreat to Venice in hopes of healing and finding peace in Roeg’s stunning arthouse horror Don’t Look Now, itself a very inspired and embellished adaptation of Daphne du Maurier’s 1971 short story.

Using a fragmented visual style involving abrupt cuts, unanticipated segues, ambiguous, often cryptic associations (the color red has never been so unsettling), Roeg creates a feeling of perpetual dread and impending doom.

This suffocating atmosphere that Roeg so expertly conjures is met with an unforgettable romantic interlude wherein John and Laura make love in one of the most brazenly erotic scenes in all of cinema. Controversial back in 1973, the love scene is still shocking and miraculous when viewed today, 45 years later.

Prolonged, explicit, and imitated many times since (perhaps most notably in Steven Soderbergh’s Out of Sight [1998]) the passion of the damaged couple is unmistakable, and their pre and post-coital embrace of one another shows a passion and an affinity that feels absolutely genuine.

“[Don’t Look Now] is an example of high-fashion gothic sensibility,” wrote Pauline Kael, remarking how “Venice, the labyrinthine city of pleasure, with its crumbling, leering gargoyles, is obscurely, frighteningly sensual here, and an early sex sequence with Christie and Sutherland nude in bed, intercut with their post-coital mood as they dress to go out together, has an extraordinary erotic glitter. Dressing is splintered and sensualized, like fear and death… Roeg comes closer to getting Borges on the screen than those who have tried it directly.” Wow!

In the years since its release Don’t Look Now is regularly regarded as one of the greatest British films of all time (a recent 2011 panel of industry experts organized by Time Out ranked it number one), often echoing sentiments articulated by the San Francisco Chronicle calling it “a haunting, beautiful labyrinth that gets inside your bones and stays there.”

Don’t Look Now is a troubling, stunning, and sensual masterpiece you’ll never forget, and it’s also the pièce de résistance of a major filmmaker at the height of his considerable powers.

Author Bio: Shane Scott-Travis is a film critic, screenwriter, comic book author/illustrator and cineaste. Currently residing in Vancouver, Canada, Shane can often be found at the cinema, the dog park, or off in a corner someplace, paraphrasing Groucho Marx. Follow Shane on Twitter @ShaneScottravis.