8. Newland Archer in The Age of Innocence – Martin Scorsese, 1992

Day-Lewis is the absolute protagonist of this romantic period drama based on a novel written by Edith Wharton and directed by Martin Scorsese. Apart from an ethnographic depiction of New York’s bourgeoisie and its ethics at the end of 19th century, the movie centers on Newland Archer, a promising young lawyer who is engaged to a young girl from a respectable family, and plans to soon marry her and live a normal life, when he meets Helen Olenska, a cousin of his fiance, May.

Helen has left her abusive husband back in Europe and Newland is appointed by his law office as her defender for her divorce and, getting close to her, he realizes there is another true life, a life full of passion, without constrictions and hypocrisy.

The hero’s character changes through the film: an aspiring, shallow young fellow becomes a passionate man deeply in love, and then desperate as he is driven by occult society forces to live a fake life that doesn’t suit him. Day-Lewis is convincing in all the three stages of Newland’s life: he plays mostly with his eyes, which gain light or fade into a glooming darkness.

7. Reynolds Woodcock in Phantom Thread – Paul Thomas Anderson, 2017

He said this would be his last performance before retiring. We all hope he changes his mind. He is an accomplished actor who gives masterly performances, and this one may be the most artistically complete. He creates an ambience by his mere appearance on screen – he needs not to work hard to put a spell on us.

This time he comes back as a meticulous, hypochondriac dressmaker who sews for the social elite and lives with his sister, letting no passion interfere between him and his work. Women serve as muses for awhile and then they are dismissed by his sister. Until he meets Alma, a country girl who decides to take the part she believes she deserves in his heart. Any way possible…

A period drama, a peculiar love story, an anti-feminist approach, a modern fairytale full of symbolisms. Whichever way one approaches this unique movie, it won’t make any difference: Daniel Day-Lewis is one more time the key to enter its magic.

6. Johnny in My Beautiful Laundrette – Stephen Frears, 1985

Taking a role Gary Oldman had just turned down, Day-Lewis played, in an engaging film that marked Stephen Frears’ early days, a gay-(ex)-fascist punk squatter who befriends his old schoolmate, a young Pakistani who aspires to become a businessman by running a launderette, and they become lovers.

It was a highly political film that didn’t go unnoticed at the time it was released. Frears, in his early days, dared to talk about Thatcher’s politics in a movie that deals with homosexuality in a country where it was then forbidden, and to tie it in with racism, xenophobia and the extreme right, cultural differences, and the growing aspirations of an immigrant community. Johnny, played by Day-Lewis, was an outcast who chose to get close to the winning side of an undeclared war, turning his back on his friends, and he did that driven by love.

Day-Lewis’ tenderness and realistic play was a big surprise, as it was his first appearance in a leading role that coincided with his Ceryl in “A Room with a View,” a totally different performance of an uptight English aristocrat. Both films were released in theaters the same week in the U.S., leaving all critics speechless on Day-Lewis’ capacity to perform such different roles in such a short period of time.

5. Gerry Conlon in In the Name of the Father – Jim Sheridan, 1993

“I asked Daniel, with whom I have worked with in ‘My Left Foot,’ because I knew that he would be interested. And that he is politically committed.”

And he really was committed. Day-Lewis in 1993 was an Oscar winner with a Hollywood blockbuster and Scorsese masterpiece under his belt. But I’m sure he didn’t hesitate a moment in making his decision. Having turned down two or three proposals from studios, he went to Ireland to find Jim Sheridan for a second time and play the part of Gerry Conlon, a young Irishman who was condemned together with members of his family for the Guildford pub bombing case, on the basis of a coerced confession taken after tortures. Because apart from the actor, there stands the man.

Just three years after the end of Thatcher’s reign, four years after Conlon and the Maguire Seven were proved innocent and freed after 15 years spent in English prisons, in a country (U.K.) whose majority was hostile toward anything that has to do with Northern Ireland due to the IRA, Sheridan brought again the question of the British juridical and police abuses, supported by Day-Lewis, who gave another of his great performances, not hesitating to close himself in a cell, being practically tortured and eating prison food for weeks in order to the spell needed once again.

4. Abraham Lincoln in Lincoln – Steven Spielberg, 2012

His third Oscar for Best Actor was for his performance as President Lincoln in a great biopic that focuses on the voting of the 13th Amendment that abolished slavery in 1865. Everybody agreed: he was the best Lincoln in American cinema. It was the first time that Spielberg was overshadowed by his protagonist, so astonishing was Day-Lewis’ acting.

Though, when at first Spielberg asked him to play the role in a film that he had planned carefully for several years, Day-Lewis refused, awed by the magnitude of the historical figure he was called to incarnate.

He finally agreed to do it (some said that it was Leonardo DiCaprio, his co-protagonist in “Gangs of New York,” who convinced him) achieving a masterly performance, both technically and sentimentally, because he managed to convince both his fellow delegates and the audience.

He let himself be “drawn into Lincoln’s orbit”; he confessed that he had never experienced that depth of love for another human being, and he became Lincoln to the point that everyone in the crew called him “president.”

From his stance – slightly bowing, hands hanging – to his voice and his feverish looks, he portrayed an ideologist that fought against all odds for what he deeply believed was his duty as Christian and as the president of United States.

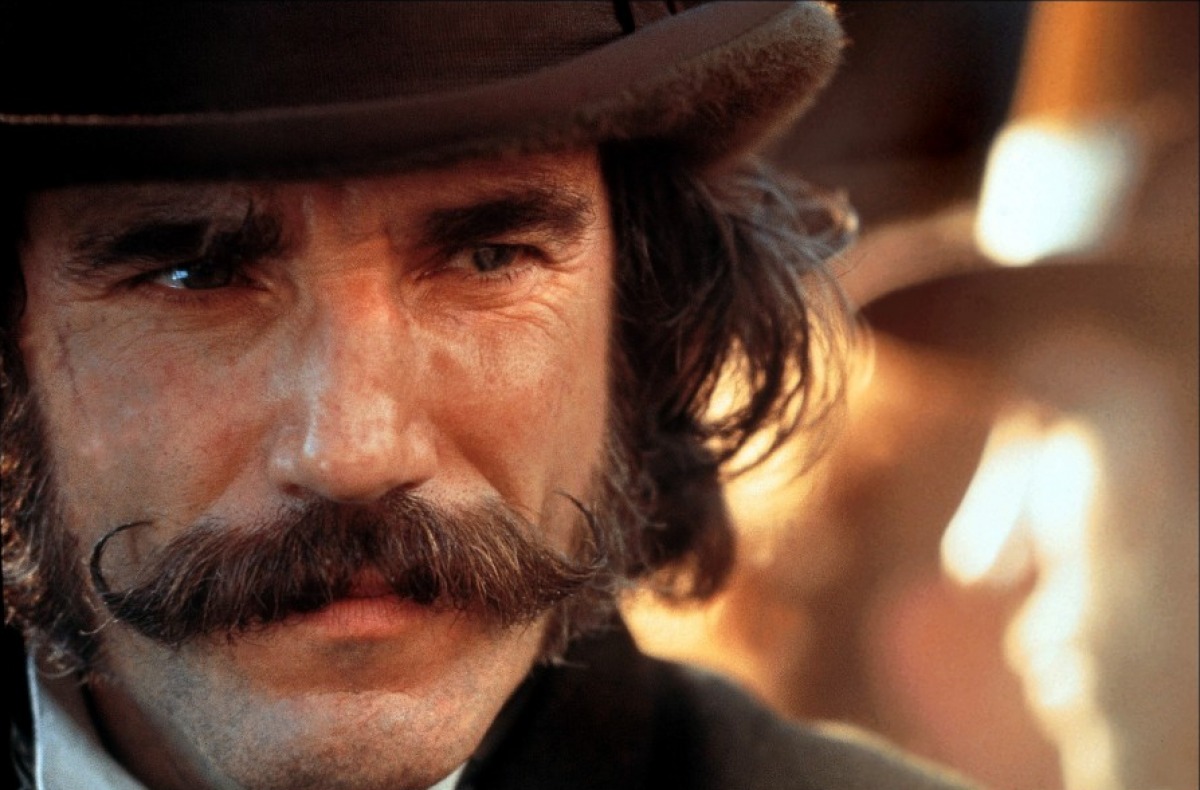

3. Bill ‘The Butcher’ Cutting in Gangs of New York – Martin Scorsese, 2002

When he’s good, he’s good. When he’s bad, he’s the best.

Filthy, greasy hair, a supposed crystal eye, his face covered with blood, masterfully butcher cutting pigs and humans into pieces, wearing fancy waistcoats and toppers, Martin Scorsese created and Day-Lewis incarnated an emblematic villain, the king of New York crime in the 1860s, Bill “The Butcher” Cutting. An ‘electrifying performance’ that added points to a film that was meant to be a great epic of New York history, based loosely on the New York Draft Riots of 1863 and depicting the life of ethnic city gangs.

Bill is pure brutality, full of unspeakable violence, the rule of the stronger one, a schematic figure that was needed to counterbalance Leonardo DiCaprio’s Amsterdam. DiCaprio was really good, but in the end, everybody talked about Day-Lewis’ performance (with 12 wins and three nominations).

The shootings took place in Cinnecità. It is said that when the film was done, Scorsese took his protagonists to a dinner in a Roman restaurant and Day-Lewis was still too much into his role that no waitress would dare to approach the table.

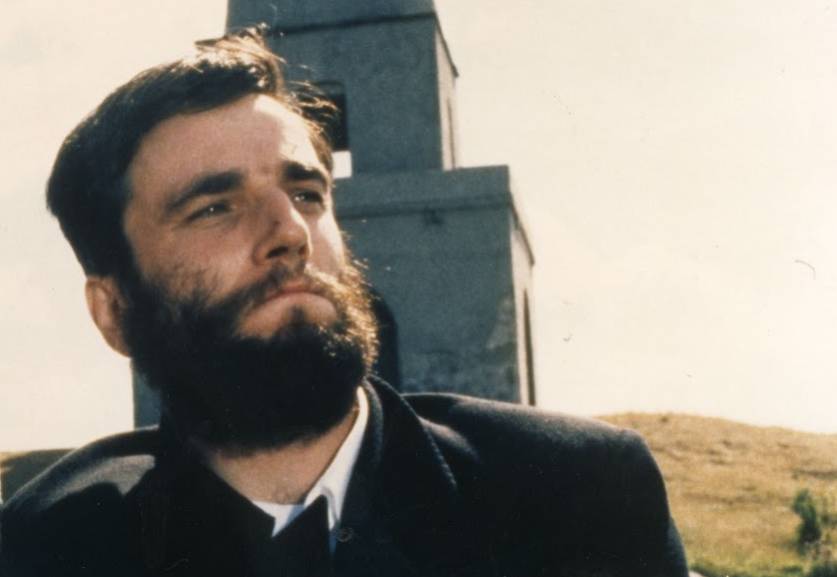

2. Christy Brown in My Left Foot – Jim Sheridan, 1989

The first of his great performances, and the first where he interprets the role of an Irishman. Of all his parental roots (English, Irish, Polish, Jewish), Day-Lewis clearly opted for the Irish one. In many cases he has declared that he feels more Irish than English, as he spends more and more time there and has acquired Irish citizenship.

I suppose Jim Sheridan – then an unknown director, planning to make his first feature film – didn’t have to work hard to convince him to play the part of Christy Brown, a working-class boy with cerebral palsy who grew up in harsh conditions and, thanks to the love he received from his mother and siblings, became a significant painter and writer using the only part of his body that could function properly: his left foot.

The role of Christy Brown drove Day-Lewis to a totally different level of acting. From a very good actor, he became a brilliant, inspiring performer with this film. That is partly due to the love everybody who worked on this film put into it – I was not on the set, but one can sense it, as with many Irish productions. It was a personal wager for Day-Lewis – this cannot be done, so I will do it. He worked hard for it: he stayed for a long period in a center for paraplegic children, he sat in a wheelchair, and was fed throughout the shooting of the movie.

And he achieved a great goal: it was one of the few times in world cinema that a person with special needs is portrayed not as a caricature but as a living human being with thoughts and emotions. An unforgettable performance!

1. Daniel Plainview in There Will Be Blood – Paul Thomas Anderson, 2007

When he’s good, he’s excellent. When he’s evil, he’s divine.

Of all his great, iconic roles, this one is his best, because he manages not only to play a part but also perform an idea: Plainview embodies the forces that built the American economy by exploiting nature and the inhabitants of the western wild lands, the territory where personal ambition was the governing rule. Starting as an aspiring silver miner, he gets involved with oil drills and becomes one of the tycoons through felony and crime. He is juxtaposed to Eli, a preacher who incarnates the plunge of theistic morality in front of the oncoming force of capital.

The fight between Plainview and Eli, which transcends the movie, is literally the conflict between medieval religiousness and the slamming power of a newborn industry – through the exploitation of the new combustible, petroleum – and the ethics of the society that this drive for growth creates.

Day-Lewis plays with everything: his eyes, his facial muscles, his body, his voice, which he changed after listening extensively to recordings of stories of that time in the west. He studied the role for three years. Anderson confessed that the film would not have existed without him.

Really, who would have played Daniel Plainview other than Daniel Day-Lewis? Who else could incarnate the inner nature of American capitalism, its disastrous impulse that knows no ethical boundaries, than an actor of Day-Lewis’ range, an actor who, apart from his eminent talent, could stand critical against the role? Who else could reveal the wild beast behind the unscrupulous man?

It’s a performance highly praised by almost everybody, which led him to his second Oscar. It showed how Day-Lewis, in the mature state of his career, could turn, like Midas, everything he touched, every movie he participated in, into pure gold. And that, of course, was by no means a curse – it was a benediction.

Author Bio: Regina Zervou is cultural sociologist who took some fifteen years to move from carnival and popular culture studies to cinema theory. An afficionado of movies since she was twelve, she loves the way reality and ‘surreality’ is depicted on the screen. When not watching movies, she loves walking the dogs, swimming, cooking for her children or traveling someplace in Africa or South America to take some pictures.