Houston, Texas native Richard Linklater, founder of the Austin Film Society in 1985, embodies the best aspects of the American filmmaker and their relevance to current film culture. Throughout nearly all of his work, his films communicate humanistic, naturalist and existential concerns and draw from influences ranging from Robert Bresson to Martin Scorsese.

Since his humble beginnings in the late 80s and early 90s to his comfortable prominence on the domestic filmmaking stage throughout the 21st century, Linklater is a self-made director who wears his attitudes and ideologies on his characters via his frequently flawlessly penned dialogue.

His newest film Where’d You Go Bernadette – adapted from the 2012 Maria Semple novel starring Cate Blanchett, Kristen Wiig and Billy Crudup – is set for wide release this October. It’s prime time for Linklater to return to recognition as a wunderkind filmmaker whose talents have not diminished over the course of a thirty-year career, but just in case his efforts are once again overlooked, let’s rank his 19 films thus far.

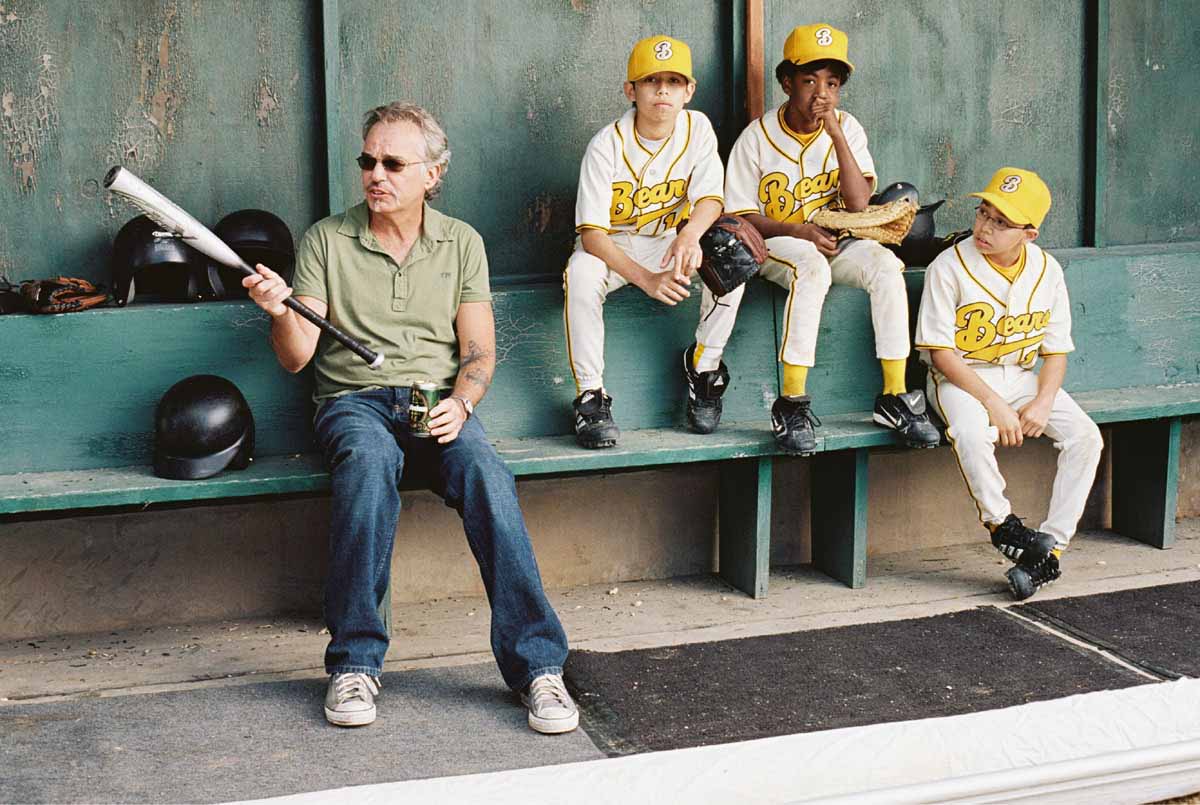

19. Bad News Bears

Written by Cats & Dogs and Bad Santa writers Glenn Ficarra and John Requa, Linklater’s tediously faithful revamp of the 1976 The Bad News Bears struggles to find a reason to exist over the course of its generous runtime.

The few original laughs of this Bad News Bears aren’t drawn from any kind of inspiration, but by sheer luck that Billy Bob Thorton – who could never hold a candle to Walter Matthau’s original Morris Buttermaker – says something nasty in the right way. Most everything in the film functions as heartless and wearying remake material. If these story elements weren’t completely cliché 40 years prior, they certainly were by 2005.

The 1976 film is no classic, but that doesn’t make the 2005 version worth any more – every kid in the dugout is a pale imitation of the original lineup. The film is the only one of Linklater’s not worth much at all, which he paid for at the box office.

18. Fast Food Nation

Known to be a voracious reader as opposed to the typical super-8-wielding young filmmaker, Linklater was fascinated enough by Eric Schlosser’s 2001 non-fiction book Fast Food Nation to loosely adapt it into his own narrative film.

Schlosser helped Linklater write the film, which debuted at the 2006 Cannes festival without making many waves. Fast Food Nation aims for comedy-drama territory but ultimately ends up being one of Linklater’s few films without much sense of conceptual cohesion or tonal consistency.

A hodgepodge of political and ethical issues and a huge helping of sanctimony make up the lacking ingredients of Fast Food Nation – the film’s ideas would have been much better served in a documentary.

17. The Newton Boys

Based on the true story of the Newton Gang, Linklater’s historical comedy-drama found him uniquely relishing in an earlier period setting and reuniting with Matthew McConaughey and mainstay Ethan Hawke.

The Newton Boys, while noble in essence, was a rare misstep in the early career of Linklater – the story of four brothers with an affinity for robbing banks between 1919 and 1924 was a box office flop and furthermore incapable of exploiting the real life tale for anything particularly thrilling or funny.

With a budget bigger than all his previous films combined, it’s ironic that Linklater was only able to offer a film as middling as The Newton Boys. Like McConaughey’s Willis losing nearly all his money on fruitless oil wells, Linklater hedged the wrong bet with this one – but some of his greatest films were just ahead.

16. SubUrbia

Adapting his own stage play, Eric Bogosian created the foundation of perhaps Linklater’s most cynical film. Giovanni Ribisi stars as the ringleader of a friend group searching for meaning while bumming around the concrete confines of a Texan suburb. His character Jeff becomes swept up in jealousy when an old friend Pony (Jayce Bartok), since turned rock star, comes back home as part of his band’s stadium tour.

Despite its darker edge, this is somehow one of the more dated of Linklater’s films. The 90s never felt so 80s, and the drama played out against the hair gel, bright colors, lack of sleeves and dated discourse place SubUrbia right in its time and place for the worst. Bogosian’s screenplay and the few revelations therein are but morsels compared to the lines Linklater can usually feed his actors.

15. Me and Orson Welles

Decent enough to recommend offhandedly, the pleasant and whimsical Me and Orson Welles finds the best in a young Zac Efron fresh off High School Musical and provides a fine platform for Christian McKay’s bravura performance as Orson Welles, if not much else.

In this adaptation of the 2003 Robert Kaplow novel, Welles recruits Efron’s young Richard Samuels to star in his famous 1937 staging of Julius Caesar – from there Samuels and Welles engage in a struggle over production assistant Sonja (Claire Danes), whom they both fancy. It’s the kind of film fit for Woody Allen on an off year, surviving by wit and romantic intrigue alone.

Embracing period whimsy with greater conviction than Newton Boys, Me and Orson Welles is about as minor a work as you’ll find in Linklater’s catalogue, yet it still aligns with his traits of optimism and thoughtful dialogue.

14. It’s Impossible to Learn to Plow by Reading Books

Exceedingly minimalist in its form, It’s Impossible to Learn to Plow by Reading Books was Linklater’s bare bones debut directed, written, produced (for a whopping $3,000) and starring the fresh filmmaker himself.

Thus marked the beginning of his days as a spokesman for slackers everywhere. The film find’s Linklater in a silent drift, simply travelling to meet up with his friend, travelling back, and appearing basically aimless in the self-directed performance.

Biographical in its nature, It’s Impossible is concerned with communicating the isolation and solace of modern day voyages – sleeping on buses, killing time in terminals. Linklater places us in many moments where dialogue is short in supply.

Mumblecore in its essence, It’s Impossible to Learn to Plow by Reading Books isn’t necessarily invigorating or exemplary of the breadth of Linklater’s talents, but it showcases a confident young filmmaker with potential to spare.