In April of this year, animation director and pioneer Isao Takahata passed away at the age of 82. This news may have gone over the heads even of casual anime viewers in America, who predominantly associate Studio Ghibli with the elegant fantasy films of Hayao Miyazaki.

Although Miyazaki does have a movie slated for a 2021 release, Takahata’s death marks a turning point for the renowned Japanese studio, which has arguably done more than anyone to validate and popularize anime in the west. With one of its co-founders deceased and several employees breaking off to form a new Studio Ponoc, now is a better time than ever to look back on the filmography of Studio Ghibli and consider how well they’ve implemented their core ideas over the decades.

For anyone remotely familiar with the studio and discussion surrounding it, categorically ranking the Ghibli movies from worst to best will seem a futile or innately subjective endeavor. Ghibli fans tend to latch on to their favorites for deeply personal reasons, and any attempt to explain their comparative worth is bound to alienate somebody.

The following effort to order the films is based on such criteria as their ambition, the depth of what they say, and how effectively they say it compared to other movies in their respective genres.

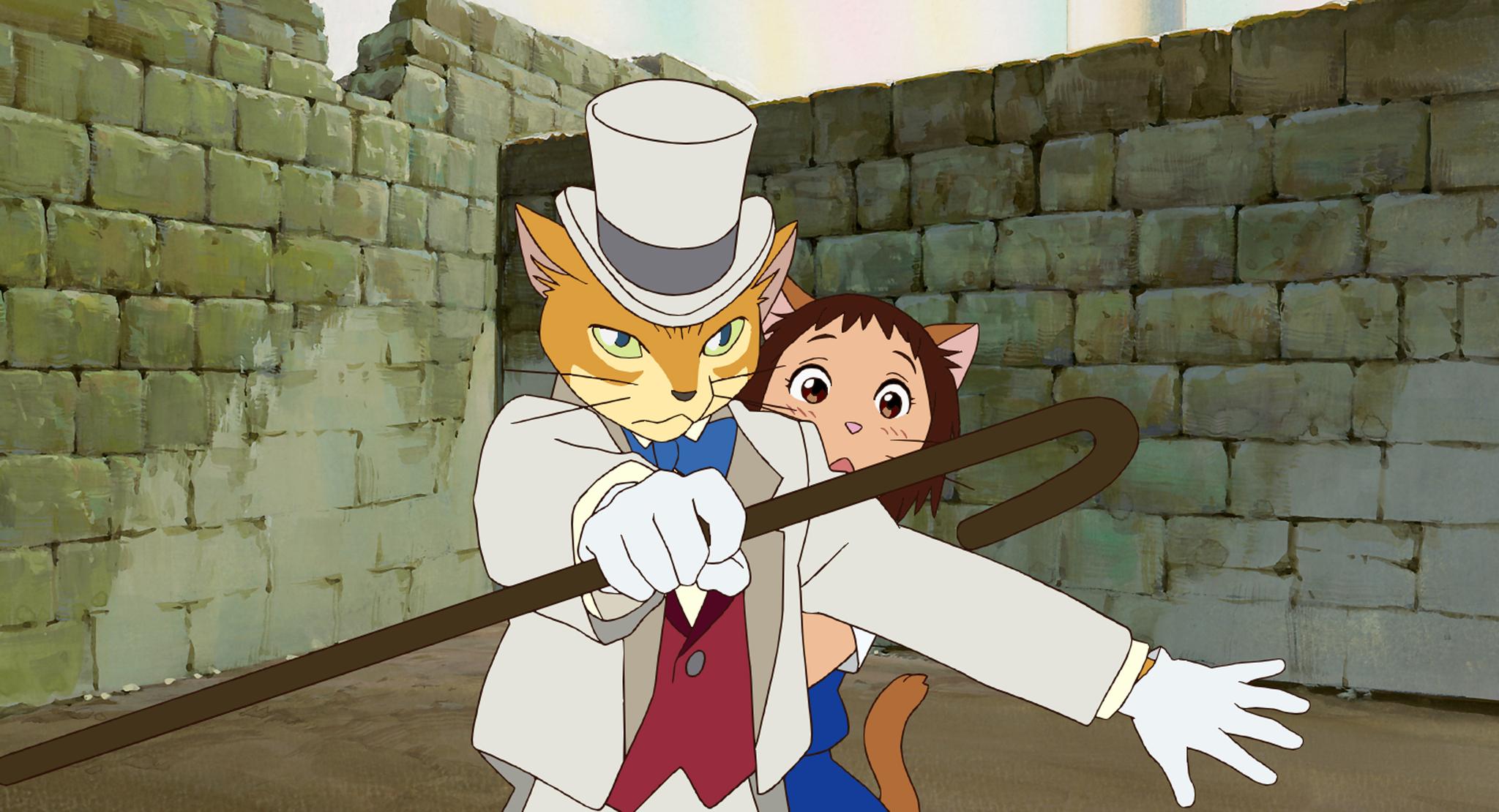

21. The Cat Returns (Hiroyuki Morita, 2002)

The Cat Returns is the Rogue One of the Ghibli Cinematic Universe, an inconsequential and flimsy elaboration on a marginal aspect of a previous film (Whisper of the Heart) for which nobody was clamoring. Its art style veers detrimentally away from Ghibli’s standard, trading in the detailed shadows and realistic character proportions of its predecessors for an overlit, cartoony aesthetic resembling a derivative TV anime.

The movie exists to gratify three niche groups: the very young, cat lovers, and Ghibli completionists who will forfeit 75 minutes of their time in the pursuit of expertise or bragging rights. Perhaps it will bring some fleeting gratification to such viewers, but for most everyone else, it is a chore with nothing to say except kiddy movie platitudes about believing in yourself.

20. The Secret World of Arrietty (Hiromasa Yonebayashi, 2010)

Of all the fantasy Ghibli movies, Arrietty takes place in a world least removed from our own, and so it suffers from the most familiarity and tedium. Whereas Miyazaki populates his directed works in large part with fantastical creatures, his Borrowers-adapted script contents itself with magnifying ordinary household- and garden-dwellers.

Hirosama Yonebayashi has the least discernible style of the studio’s recurring directors, and here he is saddled with weak source material that takes seemingly forever to go nowhere significant. The turning point of the movie takes twenty minutes to play out, as Arrietty and her mentor scale furniture in real-time to steal some sugar cubes; nothing is learned over the course of the film, and the protagonist is a bore.

If, after Stuart Little, Downsizing, Ant-Man, and multiple Pixar movies, one still hasn’t felt the onset of tiny people burnout, then the meticulous care of Ghibli’s animators may just salvage Arrietty’s thin character development. Otherwise, it’s hard to recommend the film to anyone.

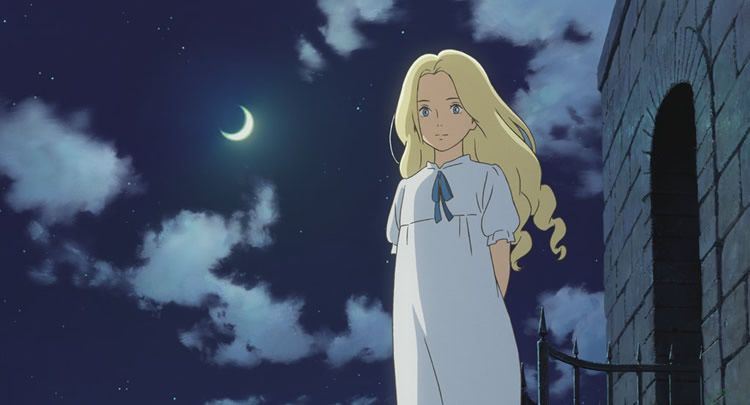

19. When Marnie Was There (Hirosama Yonebayashi, 2014)

The last confirmed movie from Ghibli until Miyazaki revoked his retirement in 2016, When Marnie Was There offers sporadic amusement if one watches it as an implied lesbian ghost romance, yet struggles to come up with any interesting visual motifs or sense of urgency, relating most of the plot in flashbacks.

The mystery feels needlessly opaque in order to inflate the runtime, with most of Marnie’s history being dispensed in a monologue towards the end rather than revealed physically.

Admittedly, the coastal setting is much better realized than the confined home of Arrietty, and some of the boating and storm scenes are pleasing to the eye. Unfortunately, the soundtrack is generic and overwrought by Ghibli standards, and Marnie isn’t differentiated enough as a white girl, her blue eyes creating an uncanny valley effect next to other Ghibli faces that don’t really look Japanese.

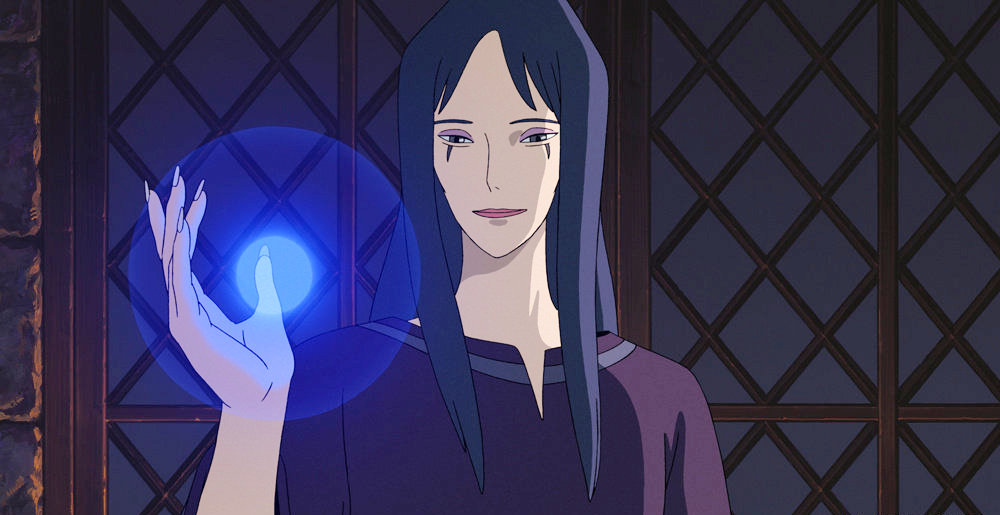

18. Tales From Earthsea (Goro Miyazaki, 2006)

Broadly written off as the studio’s only major stumble, Tales from Earthsea wants for even a hint of originality. Miyazaki’s and Takahata’s imaginations have always formed the cornerstone of their films’ success, from giant space bugs and feline buses to shape-shifting raccoons and all the specters of Spirited Away.

By contrast, Miyazaki’s son Gore looked to a western children’s fantasy series for his first feature, and failed to translate whatever made Ursula K. Le Guin’s books distinctive or popular in the first place. His Earthsea is an amalgamation of banal high fantasy tropes and images, and its presentation pales even next to Takahata’s Horus: Prince of the Sun, which came out almost 40 years prior.

In spite of its generic and tedious plot, Goro Miyazaki’s debut does have some suitably violent and grandiose sequences involving dragons, so if one can stay awake for them, it’s not the worst Studio Ghibli film by default.

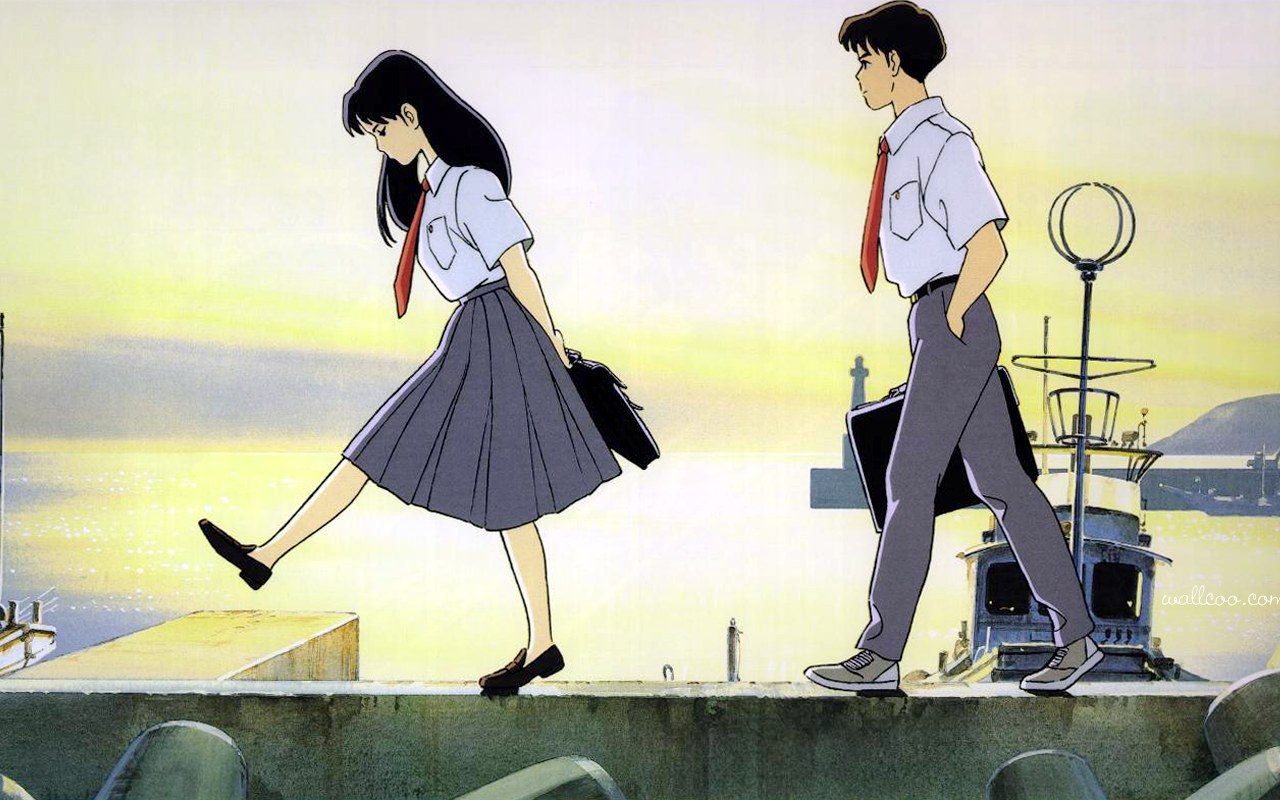

17. Ocean Waves (Tomomi Mochizuki, 1993)

As a movie made for television, Ocean Waves has indisputably the cheapest animation of any Ghibli feature, although its relatively plain and unadorned aesthetic makes it more watchable than the garish, wide-eyed characters of The Cat Returns. It has somewhat more mature content than the Ghibli movies formerly distributed by Disney, showing teenagers drinking and fooling around in frank detail.

Director Tomomi Mochizuki imbues the film with a relaxed pace and realism similar to that of a Wong Kar-Wai picture, and the marginally different focus pushes Ocean Waves to the front of the lesser Ghibli pack.

16. Whisper of the Heart (Yoshifumi Kondō, 1995)

Whisper of the Heart is beloved by many Ghibli devotees, but time and Hollywood’s lazy inertness have not been kind to it. “Take Me Home, Country Roads” by John Denver served an integral plot function in no fewer than three 2017 movies, and so it will likely strike many Ghibli latecomers with an irritating sense of déjà vu. Even if one doesn’t mind some overplayed American country, Yoshifumi Kondō’s sole feature still fails to find a satisfying balance for the multiple stories that it’s tackling.

Most of Ghibli’s female protagonists are aloof and independent children, or at least childlike in their innocence, so Whisper of the Heart comes as a bit of an anomaly in the studio’s catalogue, dealing extensively with adolescent crushes and awkwardness.

That’s not inherently to be denigrated, but Miyazaki’s screenplay bungles the romance, unable to capture a natural conversation or anything that attracts Shizuku and Seiji to each other. The middle-schoolers often verbalize exactly what they’re feeling and desire, instead of beating around the bush, nor does Kondō manage to find a more compelling visual for their affection than a glossy coat of anime blushing.

The film occasionally wanders into a fantasy world of talking cats, written by the heroine, but spends more time watching her toil away at her desk, never making clear the correlation of the two stories. The 111-minute runtime feels wasted on too many scenes of musical practice, and the ending demands the audience buy into a relationship that has been largely implied, not shown.

The art still overflows with realistic touches, boasting some of the best background paintings in Ghibli’s slice-of-life films, although nothing really necessitates that the movie be animated. The score also has some beautiful moments, though it unfortunately takes a backseat to the Denver theme.

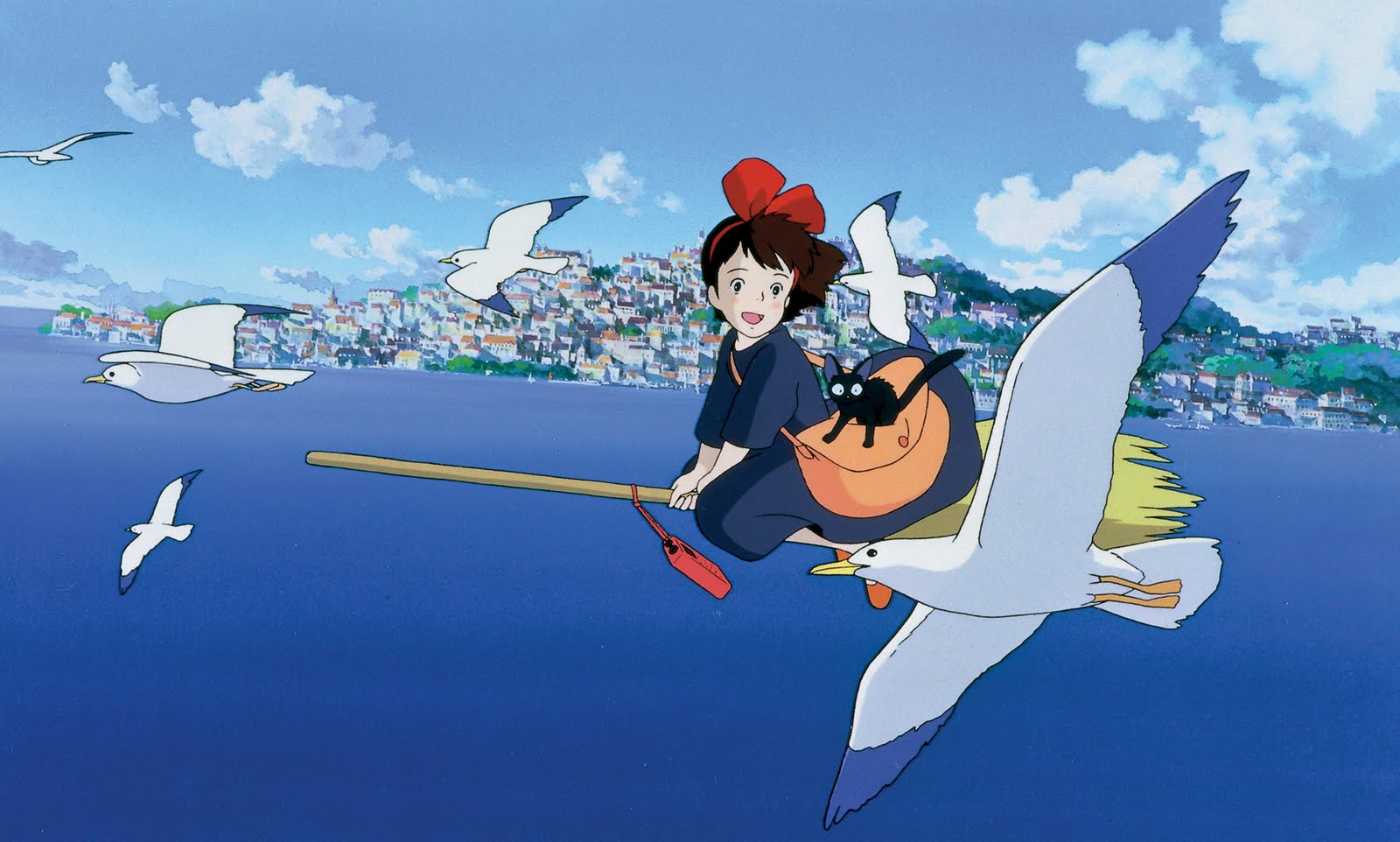

15. Kiki’s Delivery Service (Hayao Miyazaki, 1989)

Most of Miyazaki’s works center upon child or teenage protagonists, but the brilliance of his better films is that they hold appeal for both adults and children. Kiki’s Delivery Service does not excel in this department, coming out like a less effective, less concise rehash of My Neighbor Totoro.

Ghibli aficionados have often framed it as a story about adolescence and awakening to one’s vocation, but Kiki neither faces much adversity nor undergoes much growth throughout the course of the film. She starts out as a naturally benevolent neighbor, eager to use her power for delivering things, and ends up in much the same place, only she has a little more confidence around boys and is using her powers to rescue people from great heights.

Fans may dispute this complaint as nitpicking, but watching someone sit statically on a broomstick as it moves across background paintings doesn’t really summon the same emotion or excitement as the amble or run of a vivid, made-up character, a la Totoro or the Forest Spirit.