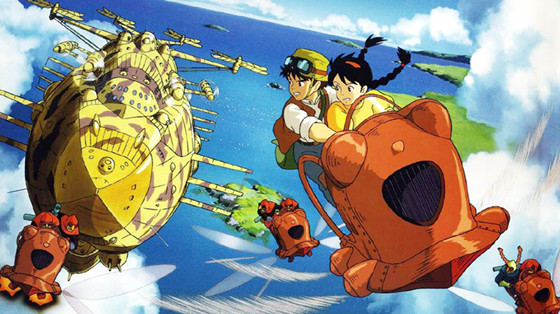

14. Castle in the Sky (Hayao Miyazaki, 1986)

Castle in the Sky, also known as Laputa in Japan, is the earliest and most westernized of Ghibli’s films, to which it may owe its enduring popularity in spite of its more mediocre and mundane elements. It doesn’t execute sci-fi fantasy as well as Nausicaa, action-adventure as well as Porco Rosso or Castle of Cagliostro (Miyazaki’s debut), light left-wing commentary as well as Princess Mononoke, or exuberant, carefree youth as well as My Neighbor Totoro.

The shrill voice acting has the potential to grate in both the original language and in the terrible Disney dub, more so than the squealing in Ponyo or Totoro, which are more lighthearted and aimed at children.

More egregiously, the diabolical Colonel Muska can only come as a disappointment, since most Ghibli movies prudently avoid a clear-cut, irredeemable villain. It’s easy to see why people remain nostalgic over Castle in the Sky, given its brisk adventure and creative confluence of medieval and steampunk art styles. The film just pales next to later, more mature achievements by its creator.

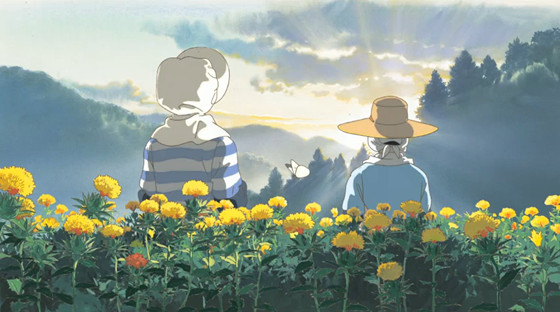

13. Only Yesterday (Isao Takahata, 1991)

Takahata’s adaptation of a manga is perhaps best known by foreign Ghibli fans for taking 25 years to get a U.S. release, long kept in limbo by puritanical Disney executives because of several scenes pertaining to menstruation. It’s a shame that this is the most memorable aspect of Only Yesterday, since its framework is ripe with potential.

The movie alternates between scenes from protagonist Taeko’s present and memories of her 10-year-old schoolgirl days. The former parts are drawn in a naturalistic way and paced very slowly, often resembling a Richard Linklater movie in their ploy to capture unfiltered human conversation. A driving scene in a traditional movie works as a transitional ligament, binding two more vital scenes and ideally cut for efficiency.

Takahata, however, follows the opposite tact, choosing to hold on mundane car rides long after his audience’s patience has walked out the door. The flashback scenes, in contrast to the present ones, have a noticeably stripped-back and impressionist style, whereby primary colors are pronounced and backgrounds faded to visualize the selective retention of Taeko’s memory. At the time, this effect made for one of Ghibli’s bolder artistic flourishes, and the film drags whenever it isn’t being implemented.

12. My Neighbor Totoro (Hayao Miyazaki, 1988)

If someone were to compile a scientific rundown of the cutest films ever made, My Neighbor Totoro would definitely be in contention. Whether big sister Satsuki is offering amiable furball Totoro an umbrella at a bus stop or the girls and their forest friends are magically raising a colossal tree into the skies, Miyazaki’s second film with Ghibli overruns with adorable scenes reveling in the spirit and imagination of childhood.

The movie is mainly designed to capture the fearlessness and innocence of its young subjects, who rush headlong into the woods without a care, driven by an irrepressible desire to explore the surrounding land. Whereas most Miyazaki films depict humans in conflict with the rest of nature, My Neighbor Totoro shows his environmentalist leanings in a more optimistic and idealized manner. The playful union of the girls and the creatures differs starkly from the dynamics of Princess Mononoke, which ends with the implication that friction will always persist between mankind and the wild.

Whether Totoro is a satisfying movie experience hinges largely on personal preference. Foregoing an antagonist, a moral, time-keeping devices, and almost any conflict besides a temporary illness in the family, Miyazaki breaks virtually all the rules of narrative filmmaking, especially pertaining to movies aimed at children. If all stories can be broken down into ones that console and ones that challenge, then My Neighbor Totoro perfectly represents the former, and given its quality, that’s quite acceptable.

11. Howl’s Moving Castle (Hayao Miyazaki, 2004)

Amply demonstrating that even an ungainly Ghibli film can be bursting with creativity, Howl’s Moving Castle aims to recapture Spirited Away’s lightning-in-a-bottle reception via aggressive eccentricity and randomness.

Miyazaki claimed the movie was “profoundly affected by the war in Iraq” and his “rage” over it, but whatever he meant to get across is buried in an incomprehensible narrative, crammed with steampunk spectacles and contrasting bright colors to distract the viewer from the absence of a central theme. While there is an ongoing conflict in the background of Howl’s Moving Castle, the basis for it and participating factions are kept nebulous.

At the end of the movie, an arcane political advisor watches the band of heroes in her crystal ball and arbitrarily says, “Let’s finally put an end to this foolish war.” Miyazaki doubtless aimed to paint the Iraq War as fundamentally pointless, but doing so through a fictional war with no clear motives, stakes, or structure doesn’t make for a compelling argument or drama.

In fact, the more one looks into the stated intentions of Miyazaki, the more the movie stands out as an inept and confused mess. The director reportedly wanted to make a film that would irk U.S. audiences, and while Howl is likely Miyazaki’s most divisive project, it still supersedes most modern Disney films in critical acclaim.

Another supposed theme permeating the film is that of old age and its blessings, but the happy resolution all but restores Sophie’s youthful beauty, leaving only her white hair as a remnant of the curse imposed on her. For an ostensibly anti-war artwork, it also spares no pains rendering the most brilliant and aesthetically pleasing explosions in the Studio Ghibli canon.

With all that said, it’s easier on second viewing to appreciate the sheer audacity of Miyazaki’s M.O., boldly disregarding a straightforward, legible plot in favor of disconnected, emotionally heightened visuals. The avian wizard Howl himself is a spectacular character, kind of like a more expressive Beast, each of his close-ups drawn impeccably.

Even if the movie mystifies as a whole, the moment-to-moment scenes of Howl’s flight, sweeping romance, and rugged mountain terrain make it worthwhile for the hardcore Ghibli fan.

10. Spirited Away (Hayao Miyazaki, 2001)

One can only wonder why Spirited Away has become the standard-bearer of Studio Ghibli internationally, having been spoofed on The Simpsons and claimed some very valuable real-estate on the IMDb Top 250. It arguably eschews a narrative more than any other Miyazaki film, and with a tone more akin to Eraserhead than to Beauty and the Beast, it doesn’t exactly cut the figure of a Disney classic or serious Oscar contender.

As a playground for the creator’s dreams to contort and run wild, Spirited Away is unimpeachable, but Ghibli has produced a half-dozen more engaging movies without skimping on bright colors and soooo weird scenarios.

Miyazaki clearly wanted to imitate the illogic and freeform nature of dreams, and for the most part he can count himself successful. Young protagonist Chihiro’s motivations are never really delineated, and she often acts contrary to what the audience would expect.

Her first impulse after recovering from the sight of her parents transformed into pigs is to seek a job in a murky factory, and once she’s subsumed into the ghost town’s workforce, she rises to increasingly perilous, altruistic causes that promise no foreseeable benefit to her. At no point does she attempt to flee the village as a normal, distraught child should, which entices the audience to gape at surreal visuals while never fully believing the direness of her predicament.

As far as treks into Wonderland go, one can do worse than Spirited Away, but the general inscrutability of the film makes it a rocky entry point into Ghibliland.

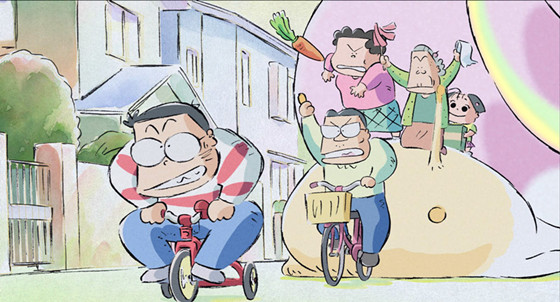

9. My Neighbors the Yamadas (Isao Takahata, 1999)

My Neighbors the Yamadas deviates drastically from the Ghibli mode, both in narrative and aesthetic; ironically, it also qualifies as the most accessible Takahata movie for western audiences. A newspaper comic strip come to life, it doesn’t resemble any other cartoon besides maybe the Peanuts TV specials, though it takes its visual design to an even further extreme, employing white space and exaggerated facial expressions to memorable effect.

Despite emulating panels that are drawn with daily time constraints, Yamadas isn’t at all restricted by its sparse, digital style, which it harnesses to create some awe-inspiring vignettes. Within the first few minutes, a bobsled ride down a wedding cake transitions into a storm at sea evoking a woodblock painting, and the scene keeps getting more strange from there.

Takahata takes an honest look at the dynamics of a crowded, intergenerational household, yet makes sure to pack the movie with enough funny and farcical moments that foreigners can relate to it. The episodic nature of Yamadas necessarily causes it to fall in the middle of the Ghibli chain; nonetheless, it’s well worth seeking out for those who’ve only encountered a few Miyazaki movies.

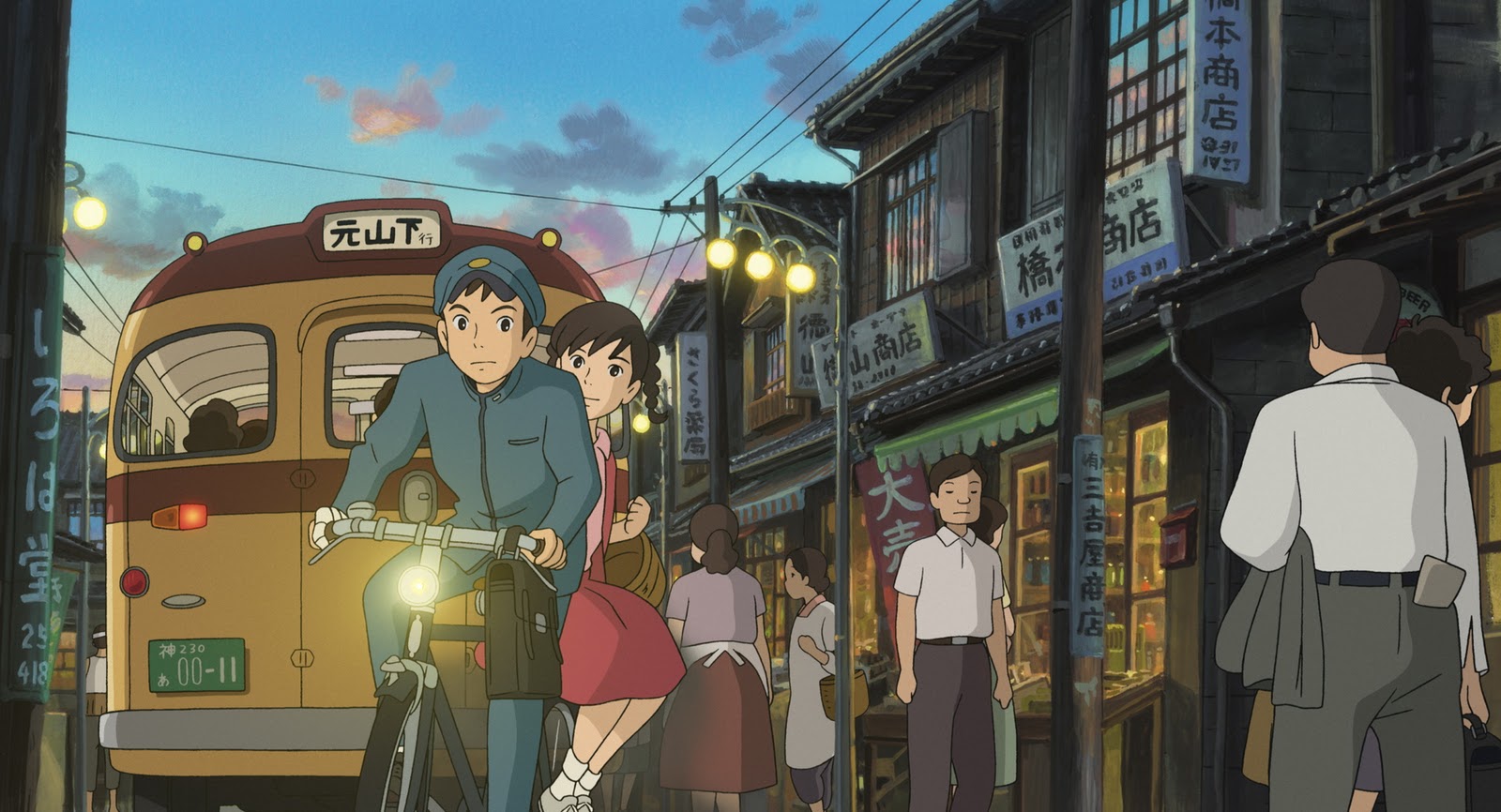

8. From Up On Poppy Hill (Goro Miyazaki, 2011)

An immeasurable improvement upon Tales From Earthsea, Goro Miyazaki’s follow-up is the most endearing of Ghibli’s slice-of-life films. Set in the lead-up to the 1964 Olympic Games, it has a peaceful tone short of being devoid of conflict, and feels like an immaculate recreation of its setting.

Whereas many Ghibli movies lament the sorrows of war and the damage it wreaks on human society, From Up On Poppy Hill serves as a welcome and positive flip side, romanticizing the reconstruction of Japan and the blooming of first love. Its closest live-action analogue might be a Yazujiro Ozu film, given that it exudes authenticity and an acute appreciation of Japanese domesticity. Meeting and exceeding pretty much every goal attempted by Whisper of the Heart, Poppy Hill exceptionally balances coming-of-age and historical storytelling.