7. Grave of the Fireflies (Isao Takahata, 1988)

One of the Ghibli Big Five and the most recognized creation of Isao Takahata by a wide margin, Grave of the Fireflies frequently stakes a claim in countdowns of the saddest stories committed to film. This reoccurring status is altogether predictable, but Fireflies’ patent determination to elicit weeping weakens it as a whole, since those who aren’t moved to tears may feel cheated and inordinately jerked-around, let down by inflated hype from sources that don’t have a wide frame of reference for anime.

From the opening scene in a desolate train station, it’s clear that the threat of death will loom over the remainder of the events, which drains the brother and sister’s struggle for survival of any tension. The viewer awaits a miserable and inevitable conclusion, and by the end has little to mull over besides the obvious deprivation of civilians in war-ravaged areas. Takahata said he adopted this structure to lessen the audience’s pain; western critics have uniformly overlooked his pity, insisting ad nauseum, “I can only bring myself to watch it once!”

Though his film is often characterized as an anti-war statement, Takahata himself has rebuffed the anti-war label several times, saying his art has no potential to avert future wars. Similarly to Christopher Nolan’s Dunkirk, Grave of the Fireflies portrays the air raids on Japanese soil like a tumultuous force of nature, and the real drama proceeds from watching how people reckon with it.

The tragedy of the film is not that death overtakes the children, but that their deaths could have been prevented if not for pride and obstinacy. Grave of the Fireflies plays out like the prodigal son parable against a wartime backdrop, only conjecturing what would happen if the son never desired to humble himself.

Takahata walked away from the bombing of his hometown at the age of 9, and the images he recalls—landscapes strewn with rubble and bodies, skies streaked with smoke—provide some of the most harrowing and vivid scenes in the Ghibli filmography.

Its reputation as the quintessential war anime is specious, especially when held up against Barefoot Gen, In This Corner of the World, or another movie on this list, but it should certainly be touted as one of the finer films from the studio.

6. Ponyo (Hayao Miyazaki, 2008)

Ponyo will never have the misfortune of bearing a fatuous label like “more for adults than for children”, that ever popular fallback of parents and older moviegoers who feel insecure in their enjoyment of Pixar movies. This is Baby Mozart for animation aesthetes, though that doesn’t at all preclude adults from falling under its spell.

Awash in beautiful compositions of blue and salmon and coral, Ponyo delivers wonder and catharsis in equal measure, and may constitute the zenith of Ghibli’s traditionally-animated films in sheer beauty. Miyazaki famously does not wait on a finished script before he starts storyboarding, and here his improvisational method reveals itself to fullest success.

Ponyo may not have the somber, high-minded themes of war and man’s place in nature that pervade Miyazaki’s career, but it aptly fulfills its calling as a whimsical and vivacious celebration of friendship, teeming with rolling waves and bounding fish.

5. Princess Mononoke (Hayao Miyazaki, 1997)

Princess Mononoke outlasts all but one other Ghibli movie at a hefty two hours and 15 minutes—a conservative length for a live-action fantasy romp, but practically too much for an animated one to bear. Legend holds that Miyazaki staved off the scalpel of Harvey Weinstein, then-head of Miramax who had reputedly tinkered with several movies for the worse.

Princess Mononoke thus came to America with all of its original baggage intact, and it certainly feels the length. The first hour of the film is methodically paced, to say the least, since it has the burden of introducing four or five parties who will converge in a final race against time.

Though many have praised Mononoke as an epic encapsulation of all the ideas that preoccupy its progenitor, the story doesn’t prop up the movie so much as its breathtaking animation. Miyazaki realizes a world that’s awesome in scope and dichotomy, prone to violence and disease as well as startling beauty.

Humans and nature share a tenuous co-existence, and when some individual actors strain that co-existence, nature lashes out in ways that earn the movie’s PG-13 rating. The fights with the spirit-possessed boars, writhing with hundreds of detailed tentacles, comprise the most enthralling and frightening sequences in Miyazaki’s career, yet he also finds profound serenity in the softly-lit glades and pools of the woods.

Miyazaki doesn’t care much about the subtlety of his messaging, and Mononoke inadvertently reveals a blatant favoritism by American critics towards Japanese imports. The story bears many overt similarities to Avatar, another technically groundbreaking film, but one is universally heralded as a masterpiece while the other reaps gleeful scorn and mockery. Regardless, Princess Mononoke still retains its enchanting power thanks to top-notch action, a majestic score, and distinctive, imperfect characters.

4. Pom Poko (Isao Takahata, 1994)

Though western media almost universally favor the works of Hayao Miyazaki, there’s a strong case to be made for the ambiguity implicit in a Takahata film. Pom Poko exemplifies his attraction to mature and complex tales where no one character dominates the moral right of way.

This decidedly off-kilter fable follows a pack of intelligent shape-shifting tanuki (Japanese raccoon dogs) that, distraught about humans developing their land, take both uproarious and troubling measures in the name of self-defense.

Pom Poko bears striking similarities to George Orwell’s allegorical Animal Farm, focusing on the conflict between moderates and radicals in a democratic society and how the latter stoke emotional unrest to curry favor for violent solutions. The tanuki even refer to the humans as “two-legs”, lending further evidence for the framework in which Takahata was working.

Pom Poko often receives flack for its supposedly onerous length, but such problems seem disingenuous considering the widespread reverence for Kiki and Totoro, which don’t even have plots in the conventional sense.

Although it doesn’t experiment as much with the animated medium as some later Takahata films, Pom Poko still provides a feast for the eyes. The tanuki take on three different forms, in addition to impersonating humans, and the animators find no shortage of ways for the creatures to utilize their magical testicles (by no means should anyone be tempted to view it through the sanitized Disney dub). A tactical ghost parade orchestrated by the animals easily compares to any scene in Spirited Away for ingenuity and other-worldly splendor.

The movie unfortunately squanders some of its nuance with a 4th-wall-breaking ending, which reduces a riveting tale of tribalism to an environmental PSA. Nonetheless, Pom Poko showcases Studio Ghibli at their most bizarre and political, and deserves to be discovered by more western viewers.

3. Porco Rosso (Hayao Miyazaki, 1992)

Short, sweet, and refreshingly to the point, Porco Rosso inverts many Miyazaki staples and tropes. Gone is the strong-willed and independent heroine, replaced with a cocksure, literal pig of a man, whose cheesy chauvinism and cool demeanor recall an old Hollywood star like Humphrey Bogart.

Porco and other characters make objectifying remarks on the beauty of his redhead sidekick, which accentuates the rough and brutish world as one cleaving more closely to historical reality, though Flo is hardly a weak or passive character.

Gone also is the vilification of technology as an inherent adversary of the environment; on the contrary, Porco Rosso celebrates exploration and flight, as a means to see the world and a symbol of man’s achievement. One of the film’s most evocative images memorializes pilots who died in combat by gazing up at their airplanes rising into the heavens.

Miyazaki’s love of aviation permeates Porco Rosso, resulting in his most comedic and purely entertaining movie since The Castle of Cagliostro. Look no further than the opening set piece, when air pirates try in vain to keep a gaggle of little girls hostage and simultaneously fight off Porco. Some critics have tried to extrapolate an anti-fascist or pacifist message from the post-WW1, Italian backdrop, but the movie is largely apolitical by Ghibli standards, which works to its benefit and distinguishes the tone from Miyazaki’s largely somber filmography.

If anything, it’s a rare tribute to freedom and political independence by the stoutly leftist director, seeing as it glorifies a drifting bounty hunter who has been released from military service. Porco Rosso may not offer the most comprehensive portrait of Studio Ghibli, but it comes closer to a decent Indiana Jones cartoon than anything else, and merits more praise than it usually receives.

2. The Tale of the Princess Kaguya (Isao Takahata, 2013)

The differences between Miyazaki and Takahata number many, though most of them can be simplified to a difference of intent with animation. Miyazaki has drawn much acclaim for making the extraordinary and fantastical look tangible and real, stating that too many animators don’t spend enough time observing other people. Takahata conversely strived to depict the ordinary as surreal, and gave up traditional cel animation after Pom Poko. Nowhere is his commitment to experimentation more highlighted than in his final film—also his magnum opus.

While Ghibli filmmakers have gradually been incorporating more CG elements in their films, Takahata and his team went decidedly old-school with The Tale of the Princess Kaguya, which is composed almost wholly of pencil sketches and watercolor paints (a climactic flying scene was digitally manipulated from background paintings). Unlike Miyazaki, Takahata did not draw anything beyond some crude storyboards, transmitting his vision orally to his collaborators.

The production documentary on Kaguya reveals that he aimed to animate drawings in a rudimentary, unpolished state. “When you’re drawing fast there’s passion,” he once said. “With a carefully finished product that passion gets lost.”

Every cut of Princess Kaguya is infused with the aesthetic concept of wabi-sabi, or the beauty in imperfection. Replete with stunning and expressionistic sequences—witness the dream where Kaguya flees the court and the world blurs around her—, the work by Kazuo Oga, Osamu Tanabe, and others marks the artistic pinnacle not only of Ghibli’s oeuvre but also of hand-drawn animation in the 2010s. Joe Hisaishi deserves credit as well for the most distinctive score of his career.

Princess Kaguya is arguably the most Japanese of Studio Ghibli’s films, being adapted from the ubiquitous story of the Bamboo Cutter. The movie follows the source’s structure to a fault, so that even an uneducated viewer can surmise that it’s based on a folk tale. E.g., the middle portion chiefly concerns Kaguya outwitting five arrogant suitors, and Takahata presents each of their failures in detail, much like a written fairy tale.

Regardless, all of the suitor vignettes are richly animated, so criticizing the movie’s length is like bemoaning too much of a good thing. Princess Kaguya focuses sympathetically on the historical position of women in Japanese society, demonstrating in uncomfortable detail the practice of blackening teeth, arranged marriages, and, most crucially, the greater freedom women enjoyed in the countryside than in a noble house.

Although the film starts off as a fantasy, for long periods it grounds itself in the female experience, such that the ultimate reversion to Buddhist lore feels like an abrupt and merciful reprieve from a stark reality.

1. The Wind Rises (Hayao Miyazaki, 2013)

Miyazaki has retired and returned from retirement several times, a process that thankfully begot The Wind Rises. In a way it’s a shame that he’s done the same thing yet again, since he’ll be hard pressed to conceive a film that better summarizes and presents the themes that have dominated his career.

Like Howard Roark of The Fountainhead, young engineer Jiro Horikoshi is driven to create objects of beauty, and he must contend with people who would pervert that beauty for ugly or destructive ends.

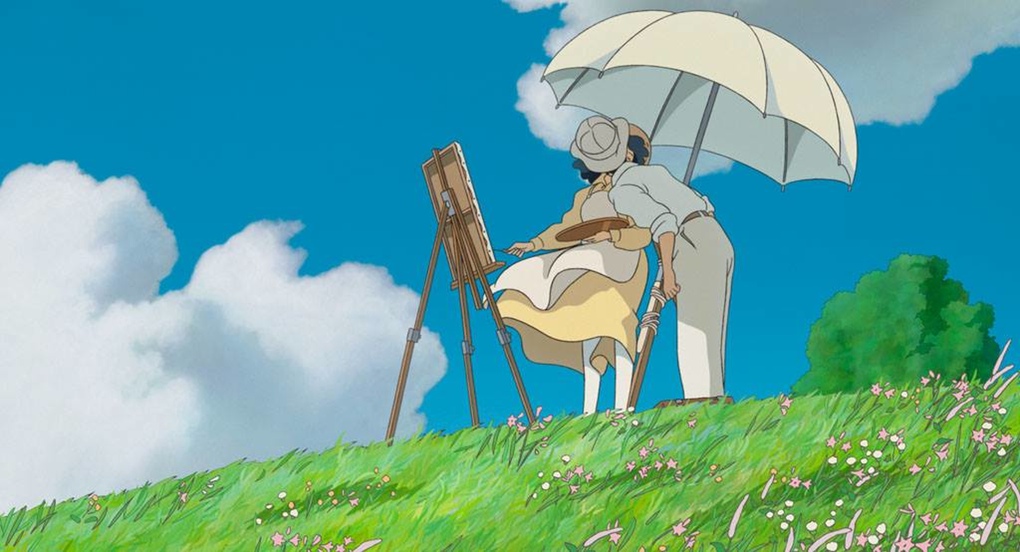

It’s fitting then that The Wind Rises should challenge Ponyo and Howl for the title of Miyazaki’s most beautiful film, being elevated by its verdant landscapes and striking use of color. True to the title, the weather effects are phenomenal, from the sight of planes cutting through cloud formations to the bending of innumerable reeds of grass and, early on, the cataclysmic force of the Great Kantō Earthquake.

More critically, though, Miyazaki has never communicated his ideology with so much pathos and sophistication. It may have little competition in the field, but The Wind Rises contains the best of Studio Ghibli’s love stories, one that doesn’t withhold physical intimacy or feel like an afterthought, as in Whisper of the Heart. It also works as a powerful vessel for its creator’s anti-war worldview, which films like Nausicaa and Howl’s Moving Castle bluntly pronounced through dialogue.

In The Wind Rises, Miyazaki trusts his visuals to convey the bleak essence of combat, which he alludes to through several eerie dream sequences. His latest film may not be a perfect one, burdened as it is with a repetitive soundtrack, but it does represent Studio Ghibli in the fullest, most definitive fashion, masterfully combining romance and historical drama, incredible machinery and untouched rural beauty.

Author Bio: Cote Keller is a recent graduate, editor, and freelance writer who is supplementing his job hunt by working at the local multiplex, which he ruthlessly exploits to see almost every domestic release. He enjoys combing through daunting, lengthy filmographies by the likes of Allen, Von Trier, or Hitchcock, and has set a personal goal to broaden his film knowledge by matching every new movie he sees with a pre-1970s one. Although his education has intervened at times, he has long maintained a media-focused website, where he writes satirical fake news in addition to analyzing entertainment, politics, culture, and the intersections among them.