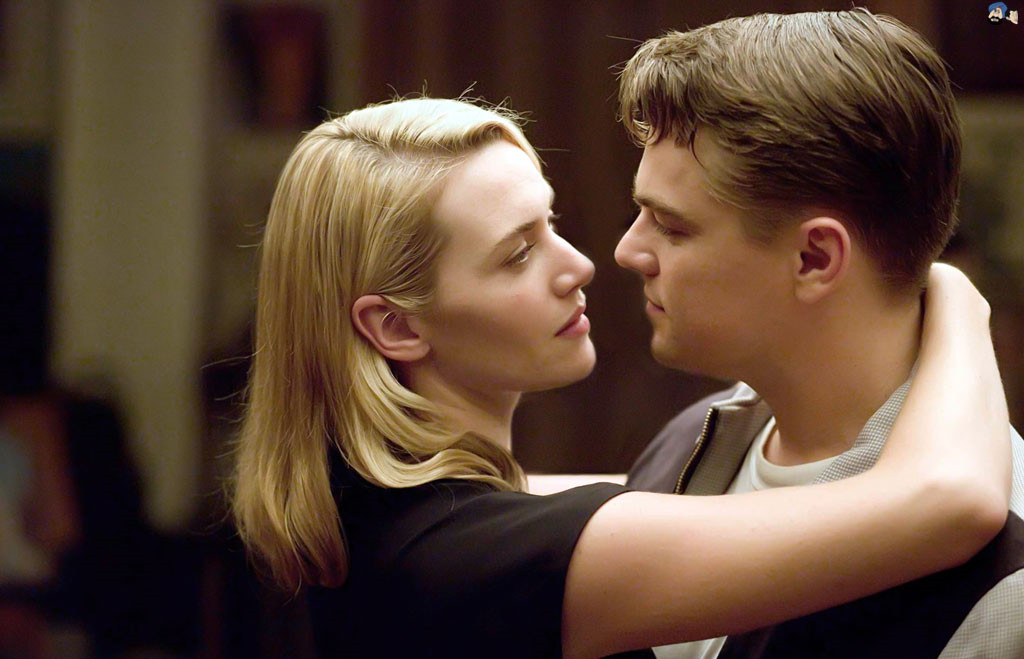

4. Revolutionary Road

Mendes returned to the suburban home front to critique the American dream once more in an adaptation of the celebrated Richard Yates novel. Removed of the irony and multiple interpretations of American Beauty, Revolutionary Road examines the disarray of the nuclear family for the own personal hell it can always become.

As much of an Oscar grab as Revolutionary Road was from the offset, the film doesn’t wallow in melodrama, but it still milks the flaring emotions of the story for all they’re worth. If it weren’t for a generic score by Thomas Newman – far too reminiscent of his contribution to American Beauty – and performances that make the film feel more like polished theater, the film would be something close to a masterpiece.

Directly contrasting the escape to better living that American Beauty showcases, Revolutionary Road heartbreakingly demonstrates how easy it is to naïvely aim to radically shift your life only to end up right where you started.

The geyser of emotions that well up from the strained marriage of Frank and April Wheeler is full of gravitas. If only Mendes could have properly directed his then-wife Kate Winslet to a more subtle final performance and helped Leo look less like he was playing dress-up.

Winslet won an Oscar the same year for The Reader after winning a Golden Globe for the performance in question, but honestly her skills have never served her better than in Heavenly Creatures so many years ago. Michael Shannon is the real revelation of acting in Revolutionary Road – he is absolutely brilliant in his two scenes.

Looking the sheer torture of love gone seriously sour right in the face, Mendes’ fourth film was a return to form and yet pales in comparison to what American Beauty accomplished with much less screaming. Revolutionary Road may bear blistering truths, but its ideas have been dissected before and better.

3. Skyfall

After Quantum of Solace disrupted the straight and narrow reboot path set by the virtuosity of Casino Royale, Mendes corrected James Bond’s 21st century course with Skyfall – only to ironically create Spectre, which would disrupt the continuation once again.

But as the 50th anniversary of the series, there was nothing more refreshing than an epically mounted, beautifully photographed and proficiently paced chapter in the franchise. Skyfall was its own contained story and yet miraculously closed a kind of narrative loop of the entire 23-part series as a whole in stirring, stimulating fashion.

Sequences like the opening chase in Turkey, sleuthing in Shanghai and the final shootout at Bond Manor stand with some of the best moments of the franchise, and Mendes and Deakins alike prove their capabilities with the fast-moving, elaborate action.

Deakins – in the best of three consecutive collaborations with Mendes – also makes the most of every set piece, landscape and exchange of dialogue with his masterful compositions. Mendes extracts excellent performances that make the one-liners glisten, and of course every actor looks damn good under Deakin’s rich lighting that accents contrasting colors.

Skillfully weaving fresh portrayals of M, Q and Moneypenny (Ralph Fiennes, Ben Wishaw and Naomi Harris respectively) into the new canon, Skyfall rebooted the series for good with a strong mainstay cast. There’s no telling where the characters of Craig’s fifth and final film – directed by Danny Boyle in a change of pace – will be by its conclusion.

Thomas Newman’s score is also uncharacteristically good for a blockbuster spectacle. Rather than blending into the background when things get loud, Newman’s future-edged score has the fury and atmosphere to elevate many scenes. The exact opposite of Quantum, every action release has plenty of delicate build-up, and this is where Newman’s music is most beneficial.

Most importantly, Mendes’ Bond film was a showman-like homecoming for the British director and a more than suitable celebration of cinema’s most iconic spy.

2. American Beauty

The Best Picture winner that put Mendes on the map from day one has aged curiously.

First off and most recently, there are the aspects of Kevin Spacey’s personal life that can make his sexually driven spiritual awakening in the film feel even more uncomfortable than it did nearly twenty years ago. But what a wide-ranging, invigorating performance from Spacey, his talents met equally by Annette Benning. Side by side the two make the Titanic reunion of Revolutionary Road look like a school play.

Of course, any talk of the film’s actual profundity is countered by those cringe-inducing speeches by the drug-dealing voyeur Ricky. In fact, the script has so much pontificating schmaltz and just plain bad writing mixed with genuine insight, social satire and convincing drama that Alan Boll’s prickly script manages to be unassumingly textured, encouraging discussion more than the film necessarily deserves.

Should we be laughing at Ricky when he shows Jane his home video of a plastic bag caught in the wind or be raptured by his every word? American Beauty covers numerous perspectives without subscribing to one entirely, making it easy to dismiss the film but much more difficult to summarize its true thematic intentions.

Boll’s first film script went through many changes and Mendes’ final product is an improvement upon the initial story. When Mendes had completed the film and it wasn’t quite what he imagined, his alterations left more optimism and ambiguity to soften the film’s cynical edge. Like Fight Club, Office Space and similarly minded movies of its time, American Beauty cleverly revels in breaking from the conformity of prescribed working class/suburban norms and expectations.

Much of American Beauty’s sharpest humor comes from Lester’s transition to a man who lives exactly as he’d like to. While the script seems to relish the kind of liberation he steadily attains, the audience can stand back – perhaps more useful than looking closer as the tagline suggests – and can see a selfish piece of shit just as easily as an average 40-something in a full-fledged mid-life crisis.

You should stand back too, because then the film’s flaws seem more insignificant. Some of the dialogue, particularly when Boll pretends to know how teenage girls speak to each other, is atrocious. Some characters are simplistic enough to make you wonder if they’re clichéd on purpose or just written flatly. Either way, Mendes manages tonal acrobatics between murder, satire, melodrama, comedy, and surrealism and gets the best from a sizable and talented cast.

As one of the better Best Picture winners of the ‘90s, American Beauty’s quality will be forever up for debate, but its attributes in several individual cases – particularly in direction and performances – will not be in question.

1. Road to Perdition

The knack for violence and atmospheric gravitas Mendes offered in this film likely lead him down the path to doubling up on James Bond. Regardless, Road to Perdition is the most distinct film of Mendes’ filmography, a stark neo-noir crime thriller that succeeds in period authenticity, palpable suspense and masterly performances, all in service of one of the most riveting gangster films that we’ve been blessed with in recent decades.

Populated with the likes of Tom Hanks (at his least cuddly), Paul Newman, Daniel Craig, Jude Law and Cirián Hinds, the original graphic novel’s trench-coated characters and gothic elements leap off the page to they’re own shadowy, beautifully grim realization onscreen.

Mendes’ film, the only one he’s both directed and produced, cinematically echoes the look of a graphic novel without resorting to the soulless style of Sin City or a Zack Snyder movie. Conrad L. Hall’s photography is extraordinary and his execution along with Mendes’ direction fulfills the dynamics of the source material’s potential to its zenith.

Amidst an uncomplicated plot clouded by double crossings, Road to Perdition’s strength is in its simplicity. A father and son relationship is set against Depression-era gangster trappings, and this solid emotional core renders the film’s implementation of refined style that much more effective.

Told from the son’s perspective, our view of father Hanks is first obscured before a superlative first-person shot shows us a glimpse Sullivan Jr.’s first exposure to his father’s real profession in visceral fashion. The film’s climax is also an impeccable display of light and shadow – the film’s rain-soaked ambiance and mise-en-scene across the board is flawless everywhere, but this scene in particular.

There’s not much to defend about Road to Perdition because there’s so little wrong with it. The film has so much to offer anyone at all engrossed by visual craft, production value, expert performances, thrilling genre moments and dramatic weight. With only his second film, Sam Mendes had established himself as an assured and capable director and Road to Perdition has aged finely enough to justify his entire career even if he sticks with the stage for good.