The Cannes Film Festival has just ended, the awards had been given, and here we go with the reviews about the movies that premiered there, in competition or in one of the numerous screenings in the most important film festival of the planet.

First of all, let’s define the research fields: the outcome is based on film reviews of English language media (Hollywood Reporter, Indiewire, Variety and others) that were on the internet before the end of the festival and the awarding of the films. In that sense, it is quite interesting to watch whether, and in what point, the critics matched with the jury’s decisions.

The Cannes 2018 Jury was a much discussed one. In a list I edited three weeks ago, there were some the films refused by the Jury. The cinematic community was both astonished and shocked as ‘heavy’ film industry names such as Malick, Leigh, Assayas and Reygadas found themselves out of the competition section.

However, it is commonplace that a glorious past doesn’t necessarily mean a challenging present. Many highly expected movies that premiered in Cannes were not up to the hopes they had raised. Farhadi’s latest movie, with first-rate stars as leads, left a rather sour taste in the opening of the festival. The Iranian director seems to perform much finer when he works with his own people in his own society. Terry Gilliam’s “Quijote” and its stretches by Amazon and its request for legal rights was rather disappointing. Maybe it was because of overly high expectations.

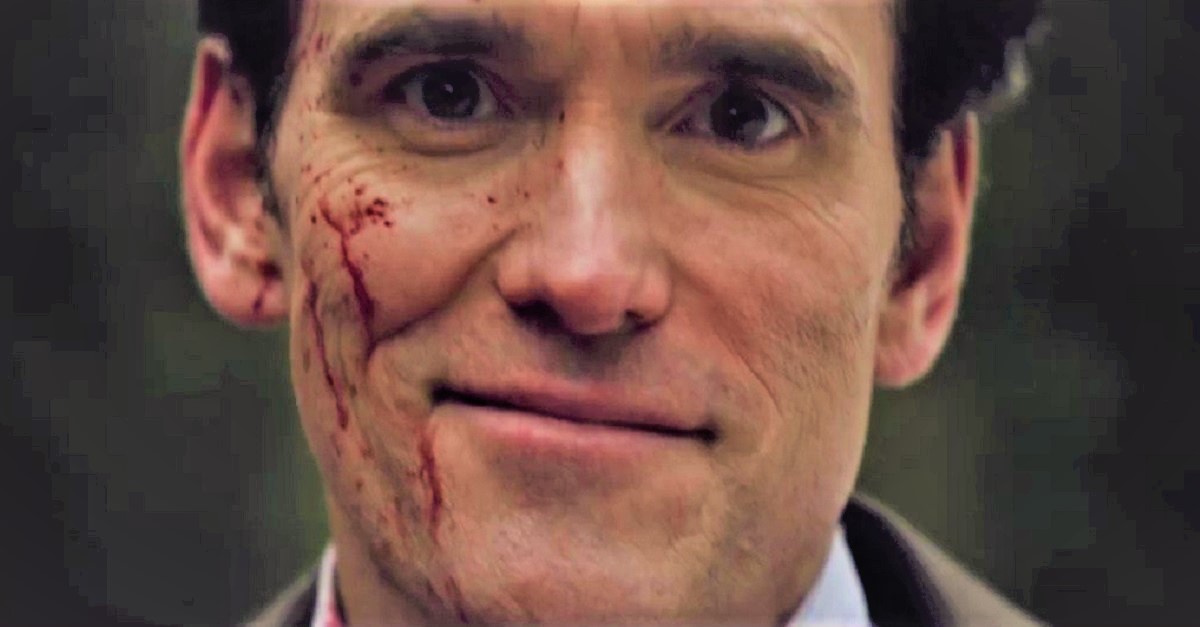

Though most critics believed that Lebanese filmmaker Labaki’s “Cafarnaứm” was the odds-on for the Palme d’Or – mostly due to the longest standing ovation in Cannes 2018 – the reviews varied from a C- in Indiewire to four stars. The same goes for “Under the Silver Lake,” with critics that varied from five stars to below zero. Let’s not speak about ‘The House That Jack Built,” von Triers’ last provocative work on a serial killer that astounded and divided the critics with its outspoken violence against women.

So after a lot of indexing and some algorithms that helped the calculation, I came up with the following list. It is obviously Asian-dominated, and I hope it will be of use for our imminent cinematic perspectives.

1. Shoplifters by Hirokazu Koreeda

What a happy coincidence between critics and the festival’s Jury! This is a heartwarming family drama by the Japanese director of small-scale, everyday stories, a Cannes regular with six nominations and three wins.

“A director who whispers instead of shouts, captures contradictions and issues through a subtle, unforced style of storytelling surprised critics (Hollywood Reporter), the Jury and the audience by the tale of a family of small-time crooks who live in penury and, nevertheless, take a child they find abandoned in the street.

“A mature and heart-wrenching return to his (Koreeda’s) socially-conscious dramas” (Variety) the film depicts the life in Tokyo’s outskirts, a 21st century Dodesukaden that highlights small hopes and dreams and casts a friendly look to petty crimes such as theft, considering it a necessity to survive and of minor importance next to the emotions’ grandiosity of the heroes.

I guess that Mike Leigh, definitely resentful after his historic epic “Peterloo” was turned down for competition, would smirk that evening at the award ceremony: a Japanese “Life is Sweet” won the Palme d’Or! His cinema, the low-profile narratives of the insignificant important ones, has triumphed in Cannes.

2. Cold War by Pawel Pawlikowski

His first time in Cannes, Pawlikowski left with the Best Director award for a passionate love story that thrilled critics and audience. “Cold War” is the story of two very different people, two artists that meet, fall in love and travel along a wounded and divided continent. The film is the story of the Europe that lived during three decades divided in two; it is the story of its people, its musics, its airs.

Wiktor works in the folk music Academy in Warsaw and sets off for a talent search in the endless flat Polish mainland. There he finds Zulu, a woman much younger than him, and together they travel in eastern and western Europe in search of music and happiness. “Their love affair seems as fractured as Europe” (Cinevue) as they go to and forth Warsaw Pact countries and experience the versatility of Cold Ear’s Europe politics and culture.

“A broken love story about broken people in a broken country” (Indiewire) on a continent that seeks to heal its traumas from World War II, omnipresent everywhere. Warsaw, Berlin, Belgrade, Paris. Cities of light and cities of darkness. In more contrasted black and white than “Ida,” Pawlikowski tries in less than 90 minutes to summarize a stiff yet hard to forget story of the struggle of Soviet socialism versus the free market economy, without giving credit to any of them.

3. The Wild Pear Tree by Nuri Bilge Ceylan

Nobody was really bothered that Ceylan’s film was more than three hours long. his longest film, together with “Winter Sleep.” On the contrary, almost everybody praised “a delicious, humane tableau” (The Guardian) with “190 minutes worth of rich material” (Thrillist Entertainment), “a visually rich chamber piece that builds elaborate rhetorical set pieces of astonishing density” (Variety). They all praised both the scenery and the photography, the vivacity of colors and shapes that is so familiar in Ceylan’s work, and the content and script of the movie.

Ceylan narrates the story of a would-be writer who goes back to his hometown – which happens to be Ceylan’s fatherland, too – with his diploma and no job and has to decide whether to take the exams to be a teacher following his father’s life, or try to pursue his dreams. The paternal figure stands between himself and his perspectives for life, which are not really settled: a gambling addict, a human wreck of frustrated goals. He walks with his son through the wild pear fields and tries to understand and advise his son, who has to take capital decisions for his life.

With just eight features, Ceylan has won eight awards at Cannes (a Palme d’Or among them for “Winter Sleep,” his previous movie). Nevertheless, this year he left with no prize other than the boffo critics on his work.

4. Burning by Chang-dong Lee

“A mesmerizing tale of working class frustrations” (Indiewire) and “a beautiful crafted film loaded with glancing insights and observations into an understated triangular relationship” (Hollywood Reporter), the sixth feature of the Korean director and writer was enchanted with his simplicity and gained the FIPRESCI award.

Vaguely based on a Faulkner story back in 1939, the film follows Jong-soo, a young boy from a peasant family somewhere around the border between North and South Korea, who works as a delivery boy. When he meets Haemi, one of his classmates in school, they have a very short and passionate affair and then she leaves in search for adventure in Africa, leaving him her house key to look after her cat.

When she returns from Africa with a new boyfriend, the rich, well-dressed Ben, Jong-soo realizes that he is the loser and has to give up. But he doesn’t. What starts as a inner look in a love triangle, in the second part of the film becomes an intriguing thriller, as Ben goes missing.

Little everyday stories that may turn to dramas, the personal style Lee has to watch the world around him through the eyes of his heroes.

5. BlacKkKlansman by Spike Lee

Spike Lee is back to let us know he can really shake ‘em down! A film that is admitted to be “one of the summer’s breakout hits” (Variety) is Lee’s own cinematic testimony and contribution to the fight against racism, for equal rights for all American citizens. A story from the 70s which, in Spike’s skillful hands, becomes very present.

It is about the unbelievable true story of a black officer in Colorado Springs (played by John David Washington, Denzel’s son) who makes contact with the local chapter of Ku Klux Klan and a Jew unaware of the race hatred that surrounds him. Extremely political, drawing lines between 19th, 20th and 21st century racism, it will surely be the topic of many heated conversations in cinematic milieu and out of it. Lee in this movie, according to the critics, tries to film the “Birth of a Nation” for the American black community, while at the same time he articulates a fierce anti-Trump rhetoric.