The Oxford online dictionary defines “stream of consciousness” as “a literary style in which a character’s thoughts, feelings, and reactions are depicted in a continuous flow uninterrupted by objective description or conventional dialogue.”

Cinema rarely engages with the stream-of-consciousness technique in the same way that literature does, since most films do not aspire to that level of abstraction and subjectivity. It is uncommon, for instance, to find a movie without “conventional dialogue,” unless there is no dialogue whatsoever.

However, many films do root themselves in an individual perspective so deeply that characters’ “thoughts, feelings, and reactions” take precedence over any objectivity or logical narrative progression. These sorts of films allow us to see the world how their characters see the world, and the plot often becomes nebulous or non-linear as we experience the subjective flow of a character’s thoughts or memories. This list collects ten of the best examples of this type of filmmaking.

10. Enter the Void (2009)

While other stream-of-consciousness films attempt to transcribe a thought process, Gaspar Noé’s “Enter the Void” simply follows a disembodied consciousness streaming through its surroundings and memories. It’s a first-person post-mortem DMT trip with a pulsing neon aesthetic that suits Noé’s vision of the hallucinated afterlife perfectly.

No, it’s not a masterpiece. Its pretensions and seedy preoccupations do distract from its loftier ambitions at times. But for better or worse, it’s an unforgettable visual experience. Noé represents the effects of DMT with luminescent, flowering patterns of light, shifting wholly into the abstract in order to capture the experience of the drug.

Noé insists that the film is not about literal reincarnation; rather, it is a dream of reincarnation, a case of human sentimentality stubbornly ignoring existential emptiness. As protagonist Oscar drifts around in spiritual form after his death, he enters the heads of other characters, participating in a strange sort of empathy that defies surrendering wholly to nihilism (though this is indeed a pretty nihilistic film overall).

“Enter the Void” should not be defended as any sort of flawless masterwork, but its commitment to portraying the subjective psychedelic experience of an individual mind makes it a good stream-of-consciousness film, and if nothing else, there is no other film out there that looks quite like it.

9. Inland Empire (2006)

As far as David Lynch’s filmography goes, “Eraserhead” or “Mulholland Drive” could be equally suitable choices here, but I chose “Inland Empire” because it tends to get less attention. Laura Dern stars as Nikki, a Hollywood actress who gets so immersed in one of her roles that the distinction between her true self and her character grows quite hazy.

Then again, in the world Lynch creates here, reality isn’t exactly normal to begin with. This is a reality defined by distorted camcorder cinematography, unnerving ambient music, and sitcoms starring anthropomorphic rabbits who speak enigmatic dialogue accompanied by an eerily out-of-place laugh track.

Nikki’s identity crisis and highly subjective experiences are the film’s main concern, far above any comprehensible plot structure. It’s kind of a drama and kind of a mystery-thriller, but it also dips wholeheartedly into horror at times, and it might be the closest thing Lynch has made to a pure nightmare (well, maybe excepting the final episode of “Twin Peaks: The Return”).

And yes, “Inland Empire” is an excellent example of stream-of-consciousness, as it wanders through Nikki’s hallucinations with no concern for plausibility or narrative logic, concerned only with representing Nikki’s own perceptions. At times, it’s more like word association than a story. The low-res DV cinematography gives the proceedings an everyday feel, as if Nikki’s visions are being documented rather than invented.

8. Dreams (1990)

If not for its title and backstory, Akira Kurosawa’s “Dreams” could simply be a series of eight unrelated vignettes. But because Kurosawa claimed that the vignettes are drawn from his own recurring dreams, we draw connections between them and begin to see the portrait of a single mind. The first three dreams are fable-like and quite open to interpretation, while the last five are more narratively direct while still highly surreal.

Although “Dreams” is more structured and straightforward than many entries on this list, it earns inclusion on account of its devotion to representing subjective images produced by a unique mind. The film’s purest moments of beauty lie in the first three dreams, two of which involve childhood.

A rainbow shining on the flowers in front of a dark mountain range, dancers representing the blooming of a barren peach orchard, a mystical woman luring a desperate mountaineer toward death – all these images set the first three dreams apart, imparting a beauty that transcends any overt message.

The last five dreams are just as visually pleasing, but some of the early promise is supplanted by didacticism. Kurosawa’s personal concerns begin to mingle with Japan’s national concerns; his emphasis on wartime guilt and nuclear paranoia seems to tap into the subconscious of his country.

A few of the later episodes contain horrors that directly contrast with the more peaceful early segments and the quiet last segment – exploding nuclear reactors, ghostly soldiers, weeping demons that wander among enormous mutated dandelions. Kurosawa does surrender to telling rather than showing, allowing his characters to bemoan the evils of mankind instead of letting the images themselves communicate the message.

That said, the images themselves are so extraordinary that the didacticism does not prevent “Dreams” from being a great film. If nothing else, Kurosawa allows us to watch Martin Scorsese play Vincent van Gogh.

7. The Tree of Life (2011)

Terrence Malick has made four stream-of-consciousness films now, and “The Tree of Life” is the only good one; everything since has fallen too far into pretentiousness and artificiality. But this one is damn good, striking a balance between abstract and concrete that Malick has not managed to recover in his subsequent films.

At the heart of the film is a family – a father, a mother, two boys – in 1950s Waco, Texas. But Malick also shows us the birth of the universe, dinosaurs, apocalypse, and a sandbar meant to be some sort of afterlife. He shows the whole scope of human existence and then refracts it all through the microcosm of one family and the beauties and pains of their everyday life.

I mentioned earlier that films with dialogue rarely forsake “conventional dialogue,” but “The Tree of Life” largely does just that. Malick employs a sizable amount of philosophizing voiceover, and even the onscreen dialogue often feels more like something people would think than something people would actually say.

Malick’s last few films make pompous claims to profundity without ever feeling genuinely profound. “The Tree of Life” is different. Sure, it’s been accused of being pretentious (and rightly so, to a certain degree), but there are times when it does feel genuinely profound.

Malick gives us a vision of human existence that is simultaneously vast and intimate, oscillating between sweeping images of the cosmos transforming and quiet scenes about growing up. And in the tradition of any Malick film, the cinematography is gorgeous.

6. Persona (1966)

The status of “Persona” as a stream-of-consciousness film depends partially on how literally you interpret the film’s narrative. Critics have advanced myriad interpretations, and there is no single prevalent reading of the film’s themes.

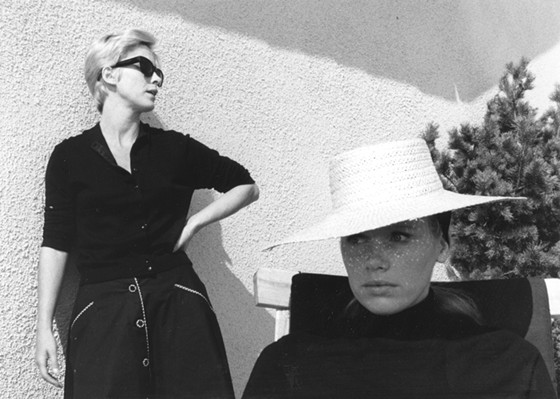

The premise is that a nurse named Alma is assigned to care for an actress named Elisabet who has stopped speaking. As the film progresses, the identities of the women begin to meld in strange ways, leading us to wonder if they might be two sides of the same consciousness.

Or perhaps they are not. Roger Ebert argued that the best approach to the film is a literal one, though his subsequent reading of the film does not feel entirely literal. Others would take a wholeheartedly abstract approach, and in this way, “Persona” has become one of the most debated films in the world of film criticism.

Is this a film about duality, about the fusion of two personalities, with one trying to devour the other? Is it about filmmaking itself, being as we see a film crew in the final scene? Is it about displacing guilt? Is it about the trauma of birth? Is it about vampirism? Schizophrenia? Lesbianism? There are no definitive answers. “Persona” could very easily be about all these things. But in any case, it is one of the densest and most compelling films ever made about the nature of consciousness and the personality.