6. Psycho (1960)

Alfred Hitchcock was much like Chaplin in that he was great talent (a fact history has revealed to be a bit more than was obvious during most of his active career years) but not considered especially bold.

His films were studio film making at its best, purely cinematic with polished production values, top stars, and first rate professionals manning every department involved in putting the whole show together. However, a change seemed to be in the Hollywood air as the 1950s ended and that change involved Hitchcock, even if he hadn’t intended to be so revolutionary.

In 1959 Hitchcock had one his biggest all-around successes with the ultra-glossy and smooth chase thriller North by Northwest. It would seem logical that the film maker would follow it up with a similar film. He tried but two potentially promising projects (one intended for Audrey Hepburn) fell through at considerable cost to Hitchcock’s production company. He needed to recoup with a big hit and one that didn’t cost so much.

Looking over the then-current US film landscape, he noted the films of cheerfully schlocky producer William Castle, who married rather ridiculous horror/thriller plots to outrageous exhibition gimmicks used to lure the less sophisticated audience.

Hitchcock and his staff conceived the idea of taking similar material but applying a more discerning and serious touch to it. The vehicle to present this idea to the world was a then-recent novel entitled Psycho by horror genre staple Robert Bloch, which was based on the ghoulish exploits of Wisconsin serial killer Ed Gein, who had a macabre fascination with the mortal remains of his victims.

Anyone reading the novel will be struck with how much transformative work Hitchcock and crew performed on it. Most notable was a rearrangement of the novel’s structure so that an event the reader could spot coming a mile off is turned into the major surprise of the film (and one that still works to this day for anyone not knowing the plot beforehand). He and writer Joseph Stefano also reconceived a major character so that the film’s other major surprise would be exactly that (as it wasn’t in the novel).

Many over the years have noted that this films sports one of the most audacious structures in film history. The rug is constantly being pulled out from under the viewer. Also, far from Hitchcock’s usual gloss, the film was shot by the crew of the director/producer’s weekly TV shows in a professional (black and white) but rather utilitarian sort of way that fit the subject of the film quite well.

All of this was quite cutting edge enough but the final stroke of genius was a Castle-like exhibition gimmick/policy. Hitchcock decreed that no one would be permitted entrance to any screening once the film had started.

Younger viewers might not know that in earlier movie going times, the customer could enter the film program at any point and, since the showings were continuous during the theater’s business day, stay in the theatre through the subsequent showing until the point at which he/she had entered came around again. Where Castle’s tricks were just audience grabbers, this rule makes perfect sense, as anyone who has ever seen the film can attest.

This film was way too jolting for many of the mainstream critics (the New York Times’ infamously stodgy Bosley Crowther was born to hate it) but the audiences were lined up around the block everywhere and the critics eventually did a rare about face (and the film received five non-winning Oscar nominations, including always non-winning Hithcock’s last).

Though the decade following Psycho, Hitchcock’s last full decade in film, would be a difficult one for him, the huge success of the film (his greatest box office hit) and the film itself would change the face of its genre.

7. McCabe and Mrs. Miller (1971)

If the New Hollywood of the 1970s was the US answer to the French Nouvelle Vogue, then, in several ways, Robert Altman was the Goddard of that movement in film history. Like Goddard, Altman was constantly seeking to subvert old genres and, thus, bring new life to them.

One big difference is that, unlike the young and brash Goddard, Aldrich had been around a long time, first making industrial films in his native Kansas City, then becoming a top television director, and a film director in the last days of the studio system, where no one wanted to hear the innovative ideas which would mark his work in the later, more progressive era.

After years of relative obscurity, Altman broke through in a big way with the now-classic 1970 anti-war comedy M*A*S*H (a pretty bold film itself). This set him up to make a number of films which, like Goddard’s works, deconstructed long standing movie types. However, unlike Goddard, Altman’s work had much humor and delighted in the interaction of unusual characters.

He would take on movie types such as the mystery film (The Long Goodbye, 1974), the criminal lovers film (Thieves Like Us, 1973), and screwball comedy (Brewster McCloud, 1971). However, the best of them all may be his highly individualistic take on the Hollywood western, McCabe and Mrs. Miller.

Taken from an obscure novel by writer Edmund Naughton, the film (shot in the rugged wilds of Canada) takes a look at the old west as it actually might have been. Instead of the clean cut pioneers arriving at sun-kissed golden plains after difficult but successful journeys, the film, set in the dank Pacific Northwest (where it never seems to stop raining or snowing), is a much grittier affair. This western world is eternally filthy both outside and in.

Such outposts of civilization as exist never seem to have seen a clean day in their existence but this is appropriate since they are populated by every sorts of outcast and criminal type known to society. Those here have failed in proper society and have struck out for a new territory . (Those who romanticize the old west often ignore, with evidence staring them in the face, that such people actually did largely settle the area in its earlier times.)

One just place is the “settlement” (and that’s being charitable) of Presbyterian Church, a grimy place, largely an ultra rustic inn, peopled almost exclusively by seedy men. One rainy night a dandyish stranger named McCabe (Warren Beatty, giving one of his best performances, despite a terrible relationship with Altman) rides in.

McCabe, according to himself, could be the hero of a dime novel due to his many dashing exploits. Seemingly never having done a decent day’s work in his life, he had come to the forsaken place with an idea worthy of himself: he virtually buys a small group of pathetic women and turns them into prostitutes in low-down tents at the edge of town.

Then one day Mrs. Constance Miller (a superb Julie Christie), a hardened long time prostitute, comes to town to tell McCabe that he’s strictly small time but, if he joins forces with her, she, as the madam, could really make it all hum. He accepts and she does just that, making the bordello the first real touch of civilization the place has known.

Unfortunately, a large “syndicate”, really an early agency of organized crime, comes to admire the enterprise and aims to squeeze a defiant and willful McCabe out, with devastating consequences.

So many westerns in film history have been stilted and artificial but, even though the number of those genre films being made had dropped off drastically, the ones made in the New Hollywood era had a convincing life to them.

M&MM is a prime example of this, bursting with life thanks to its naturalistic sets and costumes, casually profane characters and their colorful language and Altman’s trademarks of hand-held, informal seeming cinematography (achieved with much effort by the great Vilmos Zigmond), and continuously overlapping dialog from a large cast seeming to improvise their interactions.

As with many films of any kind made during that era, it’s obvious that this piece is looking at the roots of modern life through the lens of the past and finding that human nature has, in fact, changed very little with the decades of history.

Sadly, the public didn’t take to what is now (and somewhat then) is considered one of Altman’s very best films. However, it has stood the test of time to take its place as one of the best of American New Hollywood films.

8. Deliverance (1972)

From a distance, before its making, Deliverance might not have seemed particularly bold. However, appearances can be deceiving since the very thought of a big studio film with profound commercial aspirations containing such potent content would be nearly unthinkable in the current cinematic world.

The film was taken from the acclaimed first novel by the distinguished poet James Dickey. Many noted film makers had expressed interest in making the film once screen rights were secured (Sam Peckinpaugh came close to getting the job).

Very many noted actors were considered as well (such as Marlon Brando, Lee Marvin, and Gene Hackman with Jon Voight, Burt Reynolds, Ned Beatty and Ronny Cox rightly winning out ) .

The object of all the attention was a story concerning four male friends, urban types all, though two of them have some outdoors experience, embarking on a canoeing weekend on a particularly rugged section of a wild Georgia river.

It would appear to be a man vs nature story (which, to an extent, it is) but it turns much more into a civilization vs savagery tale. As the men go past the last outpost of “civilized society” they are more than a bit condescending to the unlettered and inbred locals (a fact underlined by the famous “dueling banjos” scene where the musical member of the group engages in a spirited “battle of the banjos’ with a boy who proves to be otherwise mindless and quite creepy).

They aren’t far into the feral part of the river and woods before they encounter some even more basic inhabitants leading to a nightmare of rape, brutality, carnage and murder. Even the eventual survivors find themselves forever changed by their encounter with man’s primitive side.

This sounds like some sort of cheap thriller (and many a rip-off was) but this is a film far above such considerations thanks, in no small measure, to the undiluted power of the film making.

The eventual director was British John Boorman who was then best known for the raw and potent crime classic Point Blank (1967). Consciously or not, he caught a deep seated truth of US life, where even the most modern are a short distance away from rural (and inbred) roots.

This is a film that lodges in the viewer’s mind and no one who has ever seen it can forget the scene where two ferocious backwoodsmen (played by non-professional actors) attack two members of the party and rape one of them (with the infamous ad-libbed invective “squeal like a pig!”).

Dickey’s novel had been as strong but very many film makers (and studios) would never have dared to present it at full force. The result was a big gross at the box office, fine reviews, and several major awards and nominations. For film makers, there’s a lesson there.

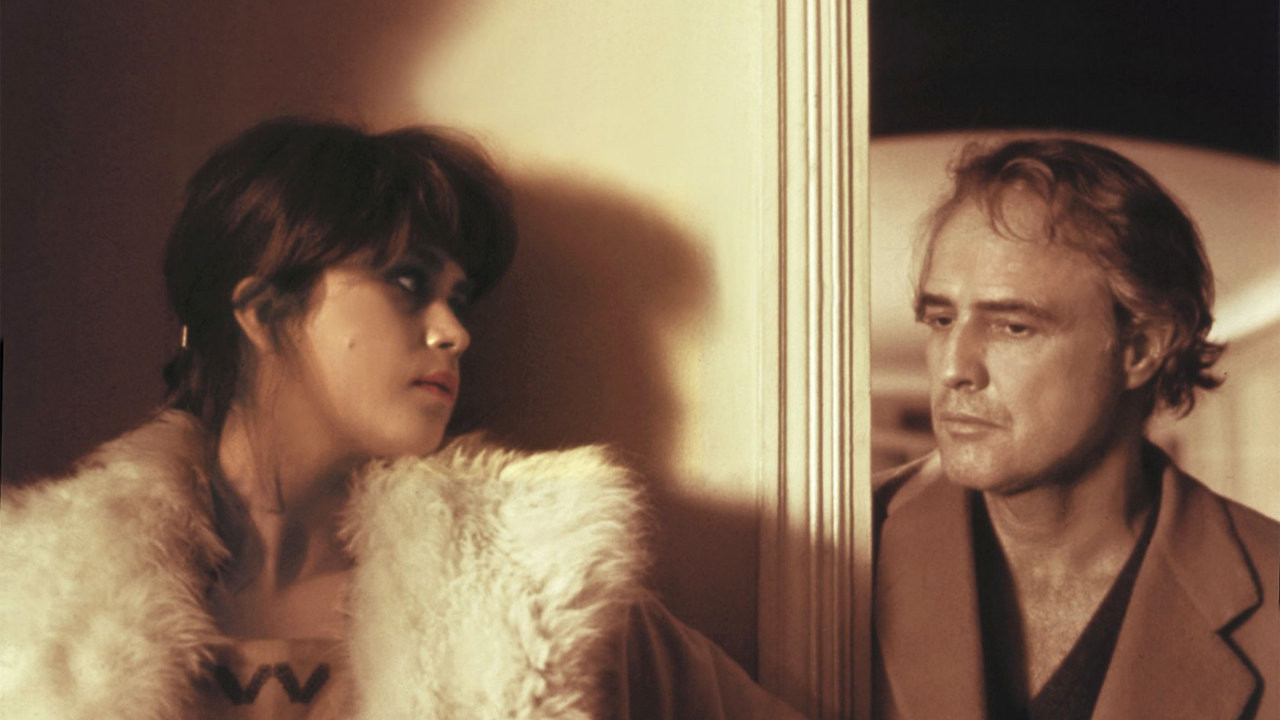

9. Last Tango in Paris (1973)

Something seemed to be in the cinematic air in the early 1970’s and not just in the New Hollywood. The late 1960s had been a time of tumultuous youthful rebellion and those youths had grown into restless and seeking young adulthood by the first half of the next decade and wished to explore adult themes in a mature and adventurous way.

This opened the door for film makers of many age group to create the kind of powerhouse films that previous cinematic mores and constraints had blocked. Surely no film blasted away at those barriers more violently than the unforgettable French production Last Tango in Paris.

The plot commences mere minutes after Paul (Marlon Brando), an American ex-patriate living in Paris, has discovered the dead body of his suicidal wife (her death occurring for reasons never really known).

He is first seen screaming with all his might on a street, then following a young woman looking for a new apartment into a rather dank building containing dwellings. He follows her into an empty apartment and has sex with her (which looks to be an act somewhere between rape and irrational mutual attraction).

The really wild thing that happens after this is that he commands her to keep returning to the apartment for more…which she does! The woman is named Jeanne (then-newcomer Maria Schneider), who was apartment hunting for a home for after her marriage to her budding film maker fiancée (iconic French star Jean-Pierre Leaud). Obviously, she is somewhat ambivalent concerning the relationship.

The disturbing thing is, that, per Paul’s edict, they tell each other neither their names nor the particulars of their present day lives (though both, particularly the man, dredge up a lot about their long-ago pasts).

This anonymity somehow liberates both of them both sexually and in expressing their unedited feelings. That sounds inspirational but, for two such troubled people, particularly the man, restraints might actually be a good thing.

Paul’s ultra-controlling sexual demands becoming increasingly extreme (as does his verbal abuse of Jeanne) climaxing in an infamous scene involving a stick of butter. Shake-ups in their lives outside of the apartment end with the pair having a chance meeting under different circumstances, which leads to a shattering climax.

The direction and script were courtesy of the noted Italian film maker Bernardo Bertolucci, who could never, even from the start, be labeled shy or retiring. However, he hit a real nerve with this one.

The central idea is that deferment of information involving identity in one aspect can lead to unfettered behavior in other, quite intimate areas of life. (Anyone who has ever chatted in an online room, especially a sexual one, where there are no real names, will understand this idea, and this film grasped the idea decades before such things existed.)

Even more controversially, the film draws a direct line between acts of sexual aggression and those with power issues (and any subsequent film pursuing this idea, to this very day, courts controversy).

Supplying a large part of the film’s forcefulness is Brando, here at his considerable best. Bertolucci skillfully persuaded the actor to improvise a number of scenes using his own past memories (and that fact is sometimes quite alarmingly apparent).

Brando ended up giving so much of himself to the film that he never quite forgave the film maker for causing him to expose so much on film for all the world to see. Schneider also gives an extreme amount to her role (and this, coming so early in her career, forever colored the world’s perceptions of her for the remainder of her rather short life).

Critical reaction was quite mixed with the great Pauline Kael (definitely no pushover) stating that the film’s opening date would go down as a historic one in the annals of the arts, while several old-line conservative critics denounced it more for content than any lack of skill in the film making.

The public? Well, it became rather fashionable so state that one had the daring to go see the X-rated film and it was a big moneymaker for a film so relatively few could see. That the picture was a genuine work of art wasn’t held against it.

10. Dogville (2003)

If there is one film maker on this list for whom boldness (whether rightly or wrong-headedly) is a given, its Danish director Lars Von Trier. Has there ever been a Von Trier film that hasn’t upset someone or failed to rub many the wrong way? (This is rhetorical question but the answer is no.)

A member of the back-to-basics Dogme school, Von Trier is also, well, to put it charitably, an original thinker. He has been noted as a harsh absolutist with many axes to grind and many issues such as misogyny (in fact, Icelandic pop singer Bjork, who made her acting debut in 1997’s Dancer in the Dark, has stated that the director’s treatment of her caused her to vow never to appear in another film, a vow she has, to date, kept).

Among his infamous hates is an almost hysterical fury towards the US (a country he has never visited, and which he vows he never will). The zenith of that hatred and near zenith of the formerly mentioned issue would have to be the truly one-of-a-kind Dogville.

Dogville, set during the Great Depression of the 1930s, details what happens when Grace (Nicole Kidman), the wide-eyed daughter of an infamous gangster (James Caan), escapes him and a violent situation caused by him by running away and, quite accidentally, stumbling upon the Rocky Mountain community of Dogville. The quite isolated place receives her quite warmly since it’s populated by kindly salt-of-the-earth types….or so they seem initially.

The longer Grace, who must survive by working for the citizens at large, stays the more the people of the town start to push their boundaries. Soon enough, Grace is literally turned into their (shackled) slave with degradation, humiliation and cruelty of all kinds heaped upon her. A twist of fate, though, puts an unforgiving Grace in the driver’s seat.

This hardly sounds sunny but the boldness lies in two elements. The first of these would be the film’s style. In keeping with the Dogme agenda, the form of the film is quite simple. Literally, there are no sets, only furniture and props with chalk lines draw on the wooden floor of the soundstage denoting one playing area from another.

Frankly, it comes across as a depraved version of the US stage classic Our Town, with Grover’s Corners gone completely rancid. (Populating the cast with familiar faces such as Lauren Bacall and Ben Gazzara increases the shock when the citizens of Dogville turn evil.)

This leads to the second, already referred to, element. This tale could, conceivably, take place almost anywhere in the world but Von Trier, setting it squarely in heartland US, tells the viewer that this deep down badness is, in fact, endemic to the US. (He underlines this with his use of David Bowie’s already jaundiced song “Young Americans” over the end titles, along with images of US failings not germane to the body of the film.)

Well, no one ever said that a Von Trier was for everybody. This one did get some rather respectable reviews, which was more than could be said about its follow-up, 2005’s Manderlay (with Bryce Dallas Howard now playing Grace), the failure of which seems to have derailed the projected third part of the USA-Grace trilogy. The film had decent enough box office returns in Europe but, wonder of wonders, failed dismally in the US. Who knew?

Author Bio: Woodson Hughes is a long-time librarian and an even longer time student/fan of film, cinema and movies. He has supervised and been publicist for three different film socieities over the years. He is married to the lovely Natalie Holden-Hughes, his eternal inspiration and wife of nearly four years.