There was a time, not all that long ago, when films, or “movies”, were not taken too seriously, certainly not as an art form. Perhaps cinema, as a viable art form, can thank television for coming along and taking the place at the bottom of the cultural arts heap. (However, artistically, TV is coming into its own, perhaps because such new video mediums as YouTube can now take TV’s old position.)

There was definitely a time when the only thing a college or university might have to do with a film was the showing of some foreign, classic or avant-garde film as a student cultural event. Most certainly, there were no courses about film. When those did start, they mostly concerned film history. Only slowly and at certain institution’s was film taught as a viable career choice and a topic worthy of in depth study.

One of the things that changed how film was viewed, at least in certain circles, was the pioneering work of the writers of the French periodical Cahiers du Cinema and those of the British periodical Sight and Sound. Added to these important voices were some excellent US writers such as James Agee, Andrew Sarris, and Pauline Kael.

All of those who contributed helped to waken people to the idea that when a film was past its box office “sell-by” date, it didn’t at all have to be just an “old movie”. (However, the fact that the US was undergoing a profound wave of interest in recent past decades, the “Nostalgia Boom”, didn’t hurt, since many older films were rediscovered and championed during that time.)

In the odd way the pendulum has of swinging wildly from one extreme to another, where many films had been overlooked and superficially judged, now many of the same films were subjected to virtual frame by frame analysis, often from many sources.

Many films, including the ones discussed on this list, are, to this day, still being written about in articles and books (several with whole books devoted to them). One hesitates to say that too much is too much, especially where there was once a dearth, but sometimes the multitude of words surrounding a film threatens to obscure the film itself.

The following list doesn’t plan to add to the theories concerning these films but to discuss why they are among the ones written about and written about and written about….

1. Persona (1966)

First of all, it must be stated that Persona could well be the stand-in for just about every film ever made by the much acclaimed Swedish film maker Ingmar Bergman. Bergman had his lighter side (see, for example, 1955’s The Smiles of a Summer Night, which hasn’t been given extensive coverage) but his heavy, often symbolic, dramas are the real focus of critical interest (and, famously, that of US film maker Woody Allen).

Part of this is the fact that Bergman liked to deal in big issues, ranging from the complicated relationships between the sexes, interior psychological conflicts, right up to man’s relationship with God or the lack thereof.

Added to this is the fact that Bergman always seemed very much a man in control of his films. His actors were always superb. His writing always highly professional (even if one didn’t like the film, one had to agree that it was what Bergman had wanted to make). He knew what to do with a camera.

The big thing after that was that he never seemed to completely spell things out. He also had an uncanny feeling for female characters, something that pleased many women and mystified several men.

Persona is a perfect film to illustrate all of this. It focuses on just two characters: an actress who has been left mute following a nervous breakdown and her increasingly chatty nurse, who is trying to bring the woman back to mental health as the two co-inhabit an isolated beach house.

The drama takes a mystical term as the roles of the woman somehow shift in a dreamlike manner (emphasized by a controversial moment where the same scene is staged twice in succession, only shot with different perspectives).

Added to this is a most unusual framing device at the opening filled with religious and sexual imagery and the presence of a young boy who might be remembering or dreaming the whole thing.

Bergman wasn’t about to explain any of this (and it might have a personal explanation, especially since he had been/was involved with the two actresses, Bibi Andersson and Liv Ullman). However, many a film journalist was happy to take up the slack. US Amazon lists some 600 (!) books under the subject of Ingmar Bergman and, of those, some two dozen deal with Persona directly.

This isn’t even taking into consideration the literally thousands of results an internet search engine will bring up, not just on Persona as a film per se, but on the explanation of the film! What does it all mean? If you can’t decide for yourself, there are many who will help you in that regard.

2. Vertigo (1958)

If a film maker has to be analyzed to a fare-thee-well, it makes sense that it would be an overtly cerebral one like Bergman. However, if this were a contest, the next two film makers on this list could more than give him a run for his money.

For many years, quite a few of them during the years he was actively working, Alfred Hitchcock was patronizingly thought of as “that funny looking little fat man who makes the mystery (sic) movies where he always plays a little part”.

That kind of thinking might well account for why one of the most studied and influential film makers of all time was never, despite five (mostly wrong) nominations, awarded an Oscar (and those were given out quite sparsely to the people and films on this list).

Once the kids who loved Hitchcock growing up took over, boy, did things change! Bergman may have some 600 books listed on US Amazon but Hitchcock has over 3000! Is there any aspect of his films or life (way too much on that in recent years) left unexplored? If so, future books and articles will surely address it (and the many websites devoted to Hitchcock will keep the faithful up to date). It’s a sign of something that Hitchcock needs two entries on this list.

The first of his much, much discussed films is one whose current prominence would have surprised many half a century ago. In 1958 Vertigo, taken loosely (as was Hitchcock’s custom) from a French novel, arrived after a difficult birth to what was, for a Hitchcock film, indifferent business and some bad reviews (Time infamously called it “another Hitchcock and bull story”).

Since it was one of the five films Hitchcock ended up owning after the initial run was finished, Vertigo, like the other four, vanished for decades, save for a couple of showings on network television (and many who saw it those times retained vivid memories of it).

Nothing seems to excite a film goer more than the news that a film is unavailable for some (usually legal) reason and then to have it return. However, the film must then live up to expectation.

When the five Hitchcocks were brought back after their maker’s death (he shrewdly left them and their disposal as a last gift to his heirs), 1954’s Rear Window was rightly hailed as the return of a major work but 1956’s The Man Who Knew Too Much, 1955’s black comic The Trouble with Harry, and 1948’s infamously experimental Rope didn’t generate all that much enthusiasm. However, even the reception of Rear Window (much written about in its own right) paled in comparison to that accorded Vertigo.

Much of this rapturous acclaimed had started during the years of the film’s absence mainly due to two writers of early scholarly works on Hitchcock, Robin Wood in his seminal 1965 book Hitchcock’s Films (which he significantly revised before his death) and Donald Spoto’s The Art of Alfred Hitchcock in 1976 (though Spoto in now in the doghouse among many of Hitchcock’s faithful for his books on the film maker’s personal life). Both, particularly Spoto, wrote in the most glowing terms about this film.

The fact that if would be also another decade after even the later book was published before many would be able to see the film (or see it again) made many a Hitchcock, or just plain film, fan pine all the more for it.

Thankfully, it didn’t disappoint. In fact, the controversial plot twist that Hitchcock used two-thirds of the way through the film now seemed the work of a real artist. (The authors of the novel had also written the book French director Henri-Georges Clouzot had based his 1955 Les Diaboliques upon and he had filmed it as written. Though that film was a hit and is still remembered, it doesn’t repay return visits in the manner of Vertigo.) Once the film was back in circulation, the literary title wave commenced.

Vertigo, for the uninitiated, is the story of a private detective (James Stewart), who has had a bad shock which left him with a pronounced case of vertigo. This plays into a strange case in which a long ago acquaintance asks him to follow his wife (Kim Novak), who seems to be the victim of a mental illness in which a long dead ancestor is willing her to her own death.

After that takes place in the middle of the film, with the detective’s vertigo preventing him from saving her, the mentally broken man is himself obsessed with the past until happening upon a rather common shop girl (Novak again) who bears a striking resemblance to the first woman.

The film is done is an ostensibly realistic but also dreamlike style. This was enough for many, many writers to pen concerning Hitchcock’s exploration of identity, obsession, the male gaze (a phrase which seemed to be invented for Hitchcock studies), gender relations, particularly domination and submission, the role of women in his films, films in general, and in society, and any number of stylistic observations. (The fact that Hitchcock infamously replaced one-time protegee Vera Miles when she became pregnant and was none too kind to Novak, also caused a lot of feminist oriented articles to appear).

US Amazon lists some 60 books alone that touch on Vertigo and the crowing achievement of it all was when Sight and Sound’s once a decade list of the greatest films of all time appeared in 2012 and, for the first time in decades, Orson Welles Citizen Kane (discussed later) was not number one. That honor went to Vertigo, not even on the version of the list that appeared in the 1980s. Those betting that event didn’t inspire lots of writing obviously don’t read film journalism.

3. Psycho (1960)

Now, as the second part of the Hitchcock entries, comes a film which was, in many ways, at the opposite end of the spectrum from Vertigo. Both were from undistinguished novels (Paramount hadn’t even done a reader’s evaluation for Robert Bloch’s novel when Hitchcock first inquired about it). Both had trouble with the critics (though, in Psycho’s case, there was a sharp turn around within the first year of its release).

However, whereas Vertigo was one of those films left high and dry at the box office due to being too far ahead of its time, Psycho caught the changing moment of its time and was the biggest financial success of Hitchcock’s career. (And, sadly, seemed to be the pinnacle, with things going downhill from there.).

Usually big hits don’t end up being the films written about but Psycho was an odd case (and about an odd case). Even the critics who originally changed their tunes about it did so rather grudgingly. The notoriously old-school British critic Leslie Halliwell gave it a high rating in his annual guide but also called the plot “childish” and the production “something of a con job” (having something to do with the film being shot cheaply by the crew of Hitchcock’s TV show). Many of the younger film writers who came after felt the need to redeem the film from those old left-handed views.

Those writers wanted the readers to know that Psycho was more than a film which cleverly misdirected the viewer (the plot famously starts off being about a put-upon secretary’s stealing her employer’s money in a moment of weakness, then veers into a story of murder and insanity involving the inhabitants of a run-down motel and the creepy house standing behind it).

It was to be understood that this was one of the great works of macabre fiction and that Hitchcock’s genius not only dressed up a routine novel (which was told in a straightforward fashion) but deepened it considerably.

US Amazon list over a hundred books relating to this film. In fact, the film’s famed shower scene, one of the most famous in film history, has one scholarly book devoted to it alone! Past that there are more books and articles on gender (again), identity (again), male gaze (again), male-female relations (again) and many more subjects the legion of Hitchcock writers love to discuss.

Is it all overkill? Maybe and maybe not, since this writing has helped to bring some of the best films cinematic history has to offer to something like their rightful place. In the end, what’s written can be accepted or taken with a grain of salt but the films will always be there.

4. 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)

Though the films they made and their public personas were little alike, Alfred Hitchcock and Stanley Kubrick did share a thing or two in common. Both were men at the top of their professions and both respected even after their box office heydays were over (though neither much admitted to knowing the fact that the glory days were over). Both controlled every aspect of their films (which drove Kubrick to create in isolation by working in England for the bulk of his career). Both also made films that were, for the most part, financially successful, a fact which gave both a lot of clout for a lot of years.

More importantly, those films were built on complex and sophisticated ideas that, if overtly stated, might have kept the crowds away but both had good track records for bringing those crowds in. No film illustrates that point better than the one under discussion.

Kubrick made great strides with every film from his amateurish self-financed feature debut, 1953’s Fear and Desire, up through 2001 at the very least. He established himself as a major force in the film world with 1958’s Paths of Glory, 1960’s Spartacus (though he always despised the film since he had so little control over its making), and 1962’s Lolita (though censorship defeated him at certain points in the making).

However, Kubrick as a cultural giant started with 1964’s Dr. Strangelove, or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb. That sharp witted Cold War satire (on a subject few were finding funny) put him in another league entirely (though the Academy thought My Fair Lady more important). It was obvious that Kubrick was a sophisticated film maker whose content matched his composed, controlled, elegant visuals. That film’s success set the stage for the one that, to many, put him among the all time greats.

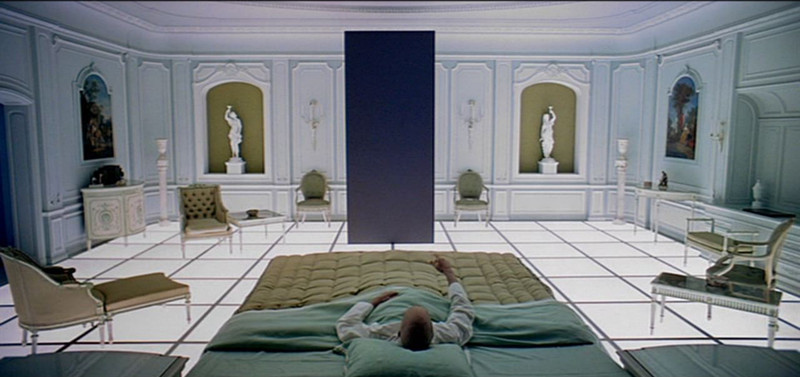

2001 was taken from a short story entitled The Sentinel by famed science fiction author Arthur C. Clarke. The basic story takes mankind from the prehistoric days (with trained dancers in very convincing ape-like costumes) to the title year (which seemed a very long time away when the film was being made).

In each of the film’s episodes mankind encounters objects, messages, spectacles engineered by a higher and remotely alien intelligence, always pulling man forward. The big motif that made this film so much more intriguing than most of the sci-fi films which came before is that Kubrick put in virtually no exposition and no explanation. No actors with speaking roles appear until the film is almost half over and, at that, they speak rather little for the rest of the film. Such speech as there is explains nothing.

In fact, one reason the film has always attracted so much attention is that the point of view is comparable to creatures studying lesser beings (mankind, in this case) and watching how these beings behave when confronted by a superior intelligence.

Truth to be told, much of the writing on this film seems to be trying to live up to that intelligence. One may formulate the meaning of this films to one’s heart’s content but, as long as there are films, it’s a safe bet that someone will be writing something that claims to get to the bottom of this one.

5. L’Avventura (1960)

While Italy’s Michelangelo Antonioni shares the sort of iron autonomy which marks the works of Hitchcock and Kubrick, there much of the similarity ends. While both were long considered commercial film makers (and rather reliable ones for a long stretch of time in both careers), Antonioni pretty much always made the type of films which fairly screamed “analyze me!” and which, if they made money, did so purely accidentally (the fact that 1967’s Blow-Up was such a big hit was jaw dropping, especially in light of its troubled production).

However, much like Kubrick, Antonioni didn’t like exposition, only to an even greater degree. He would show and allow to be heard only what would go on in the time span of the film’s plot with no elaboration or any of the characters spouting dialog which sounded if it was written just to let the viewer in on a fact or two. This is a very sophisticated approach, but it sometimes made audiences crazy, never more than in the film that paved the way for his decade and half in the international spotlight.

At the 1960 Cannes Film Festival, L’Avventura was roundly booed by the festival’s attendees, yet it was given a special award at the Festival’s end for “the beauty of its images and for helping to create a new international film style”. The ever predictable Bosley Crowther said it played like a film missing several reels (though he later included it in one of his books on the great films of cinema history), while Pauline Kael praised it for bringing a new feeling to the cinema (and she cared little for the types of films which followed in its wake).

L’Avventura is truly the sort of film to provoke mixed responses. The first time a viewer sees it, the film can be slow and frustrating but it tends to come back in the mind and reveal itself more and more in hindsight. One big reason for this is that the those coming to the film might reasonably expect it to tell a conventional story (the style doesn’t at all look avant garde) and that leads to disappointment.

Upon reflection, its easier to see that the film is really a study of the human condition, modern era, seen through the prism of Italy’s bored and shallow jet set (and between the films of Antononi and Fellini commenting on this group, they must have been the next best thing to plastic).

The film opens with a lovely but most unhappy upper class young woman named Anna (Lea Masari) who is embarking on a long weekend yacht trip around some barren and rocky little islands off Italy’s coast with, among others, her best friend Claudia (Monica Vitti) and Sandro (Gabriele Ferzetti), the architect with whom she having a going-nowhere relationship, one of the root causes of her moroseness.

While the group is exploring one of the islands, Anna vanishes. At first everyone is concerned but after a day or so passes, the friend and lover simply enter into a complicated romantic relationship of their own! Those wondering about the fate of Anna, as it happens, are the wrong audience for this film, for that is never even remotely addressed again. Therein lies so much of the reason for all the writing about this film.

Antonioni wasn’t being conventional and it took a bit to get a lot of viewers up to speed. (The fact that so many viewers cared about Anna and those in the film drifted away is, in fact, a major point of the film.) With much time elapsed and many of the ideas of this and Antonioni’s subsequent films incorporated into many film makers creations, the bulk of the writing about this film may be over now but a lot of ink got used up for a lot of years back in the day.