6. Pickpocket (1959)

Joining Antonioni in the realm of the art house film maker is another austere artist with a spare and sophisticated story style, France’s Robert Bresson. The two men both started their film making careers in the late 1940s (though it took many years for Antonioni to become internationally known) and both seemed devoted to an intellectual cinema, shorn of showy, crowd pleasing acting or clichéd scenes.

Antonioni said in interviews that the actors weren’t important and that he could achieve the same effect with amateurs (though the one time he really tried that, with 1970’s Zabriskie Point, the results didn’t bear him out). By contrast, after the beginning of Bresson’s career, by which time he had gained control over how his films were made, he always used non-professionals (though two later decided, to his chagrin, to become actors). He controversially instructed them to speak in the most inexpressive monotones while saying all lines and make as few gestures as possible.

Allied with this, the scripts always revealed virtually no details beyond what the viewer sees on the screen. Bresson resolutely kept outside of his subjects and at a distance. Somehow, this sometimes off-putting technique seemed to allow the viewer to feel the internal truth of the film’s Bresson created.

Nowhere was this more evident than in Pickpocket. The film focuses on a young man (Martin LaSalle), who is, as the title proclaims, a pickpocket. The reasons why he is one forms the crux of the film. He is intelligent and attractive and capable of making a decent place for himself in society but chooses not to.

This may have something to do with his relationship with his dying mother, which looks to be loving but conflicted, though the viewer only sees the very end of it and that is seen quite discreetly. He also looks to have feelings for the young woman who, out of sheer kindness, tended the mother when the son couldn’t bring himself to be near her. Also, though the young man gets progressively better at conducting his criminal activities, he feels no satisfaction from them.

The fact that the film contains the young man’s first person voice over narration gives little illumination since he is quite terse and not forthcoming about his motives or feelings. Incredibly this film, which operates at a remove like all Bresson films, manages convincingly to come to one of the most incredibly moving finales in film history.

How is this possible? Well, many a book and article would like to explain it for the viewer. Many film writers and makers are quite taken with Bresson’s work (Hollywood film writer and sometimes director Paul Shrader openly admitted stealing Pickpocket’s ending for two of his own films). How did he say so much by seemingly doing so little? Of course, the so little actually took a lot of doing and thought (and few seem to want to follow his actual path to get his results).

However, in addition to his effect on the cinematic world, Bresson in one of the greatest (and relatively few) moralist and philosophers to have worked in film. Much of the writing about him centers on the moral issues and questions his work raises and the way he looks at the world in a harshly realistic, yet never unkind or inhumane way.

It says much that Pickpocket, only 79 minutes and filmed in the most deceptively plain style imaginable, regularly tops the list of great French films, especially those made after the classic era of French cinema and is considered a world film treasure.

7. Belle de Jour (1967)

A cinematic world away from the very serious, very austere cinema of Antonioni and Bresson, the films of Spain’s Luis Bunuel, the screen’s foremost surrealist, are wild, colorful, excessive, yet every bit as mysterious as the films of the other two.

Due to a run-in with the Spanish government and the Catholic church in the early 1930’s, Bunuel wasn’t allowed to film (certainly not in Europe) for over two decades. Perhaps due to this, his career didn’t tail off as did many film makers. Instead, he created some of his very best films near the end of his creativity (and life).

Though many of those films, such as 1968’s Tristana or 1972’s The Phantom of Liberty, are as surreal and immaculate as the film under discussion (and equally good) for a number of reasons, Belle de Jour is the film which has always excited the most comment (and writings) among those films.

Belle, taken from a novel by Joseph Kessel very famous in France, centers on Severine (Catherine Denuve, giving one of her best performances), a very beautiful young wife whose husband is an up and coming and handsome young exec, who is already giving her a plushly comfortable life in an elegant home. The problem is that, well, having it all just isn’t enough.

By a chain of circumstance, Severine stumbles into the world of upper class prostitution, only during the daytime hours when her husband is working. The kinks and degradations of the various clients (some quite aristocratic) greatly stimulate the glacial beauty (with one surprising session matching her own fetishes exactly) but what good end can there be to all?

Since the film is full of surreal moments to complement the more realistic satire (though even those are filmed without visual exaggeration) , it also stimulates…mostly those with a need to interpret. Much like Severine, this film seems to keep some part of itself secret and mysterious. The main character is never an open book, though the viewer sees her shadowy moments and flights of fancy, and neither is the film.

Perhaps it’s human nature to always try to fathom the opaque and recessed. Back in the 70s and 80s, when film scholarship became a big cultural marker, exploring the films of the great and wonderfully eccentric Bunuel became a major part of the more advanced film writings.

Belle was a breakout film (though he had done some good films upon his return to Europe, this one seemed to be the film that put him firmly back in the big leagues) and a success de scandal and a celebration of a great emerging star (she had hits in Europe previously as well but this showed her to be a world class actress). Perhaps today Belle is more taken for granted as an established classic but it still inspires discussion and lots of ink.

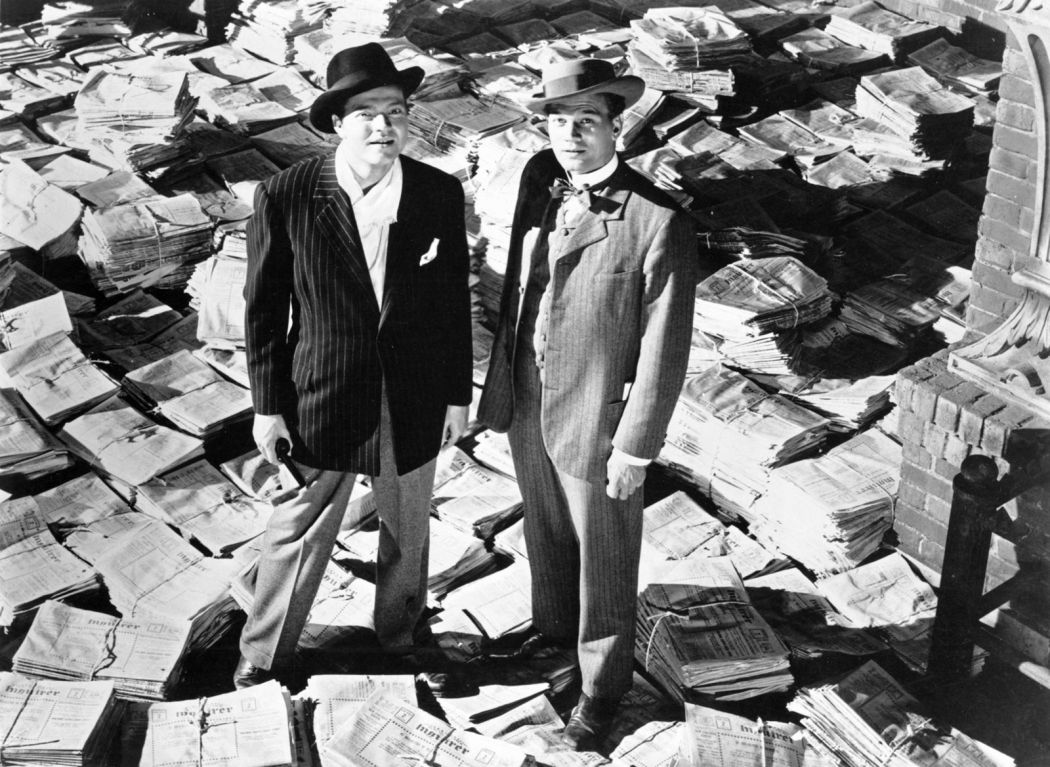

8. Citizen Kane (1941)

Yes, this is the film Vertigo knocked out of the number one position on Sight and Sound’s poll but it is doubtful that there will be any dearth on writing about this eternally famous film.

Kane is, of course, the creation of then stage and radio wunderkind Orson Welles, then only 26. As the many accounts of the making of the film relate, it was born in controversy, delivered to an initially indifferent public (account differ on the facts of the film’s profitability) and, after years of obscurity, emerging as “the greatest film of all time”.

Is there, in fact, such a thing? However, a case can be made for Kane, a treasure box of technical innovations and sophisticated storytelling, to be the most influential film ever (many film makers have listed it as the film which made them want to become filmmakers).

Kane is unusual in that much of the writing about it doesn’t explore themes and meaning but, rather, camera set-ups and complicated shots and devices, the nuts and bolts of the film, as it were. Also, as stated, the colorful events surrounding its production have been related in book after book, after book.

All of this surely started in the late 1960s and early 1970s when books such as Crowther’s The Great Films and William Bayer’s The Great Movies started proclaiming the film the best ever. However, the literary piece that caused reverberations still in motion was New Yorker critic Pauline Kael’s lengthy article “Raising Kane” which controversially claimed that billed co-author Herman Mankiewicz was really the sole writer of the film, despite Welles having himself listed as co-author.

Many Welles acolytes over the years have felt the need to write accounts defending the auteur, whose career either went steadily downhill or flourished amidst adversity, according to the writer’s sympathy or judgement (of course, there are also some tearing Welles down).

In the end, Welles was always a polarizing figure and it shouldn’t be surprising that that the one film in his cannon virtually everyone agrees was a major triumph would be controversial ever after. And, yes, there were many articles from the faithful lamenting the results of that poll and commenting on the unfairness of it all.

9. 8½ (1963)

Some twenty years after Kane came Italian film maker Federico Fellini’s 8½, another film destined to be a film maker’s favorite and one much commented upon and written about.

The film couldn’t be more autobiographical. Fellini had just had his biggest international hit with 1959’s La Dolce Vita, a film much acclaimed at the time and for years thereafter. After that he….didn’t know what to do, literally. Eventually, he came up with this film about a noted director who had just had a big hit and didn’t know how to follow it up.

Fellini not only put his professional crises on display but a big part of his personal life as well (probably more than the others involved might had liked). He also dramatized and illustrated his fears and fantasies which went along with his creativity. (Even the title was biographical, since this was his 81/2th feature, given that he co-directed his first film.)

Was he being daringly creative or self-indulgent or both? Well, a lot of print has tried to answer that question over the years. However, with the years, the film’s stock has gone up, especially among young film makers who note that it accurately captures their experiences in filmmaking (and even the fantastical moments caught the feelings of the film makers during the process).

A lot of ink has been spilled about the way Fellini allowed his creative process to be displayed and examined and a very lot of that ink concerned Fellini’s view of women and how they fit into the lives of men, especially artistically successful men (and the film is adorned with women of all types in both the director’s past and present and his own icon-like life is examined in great detail as well).

Many of those who write about the film feel it to be the best dramatization of how making a film works. Perhaps those not interested in the film business wouldn’t be receptive to the type of writing which surrounds this film but what passionate and discerning film watcher would that be?

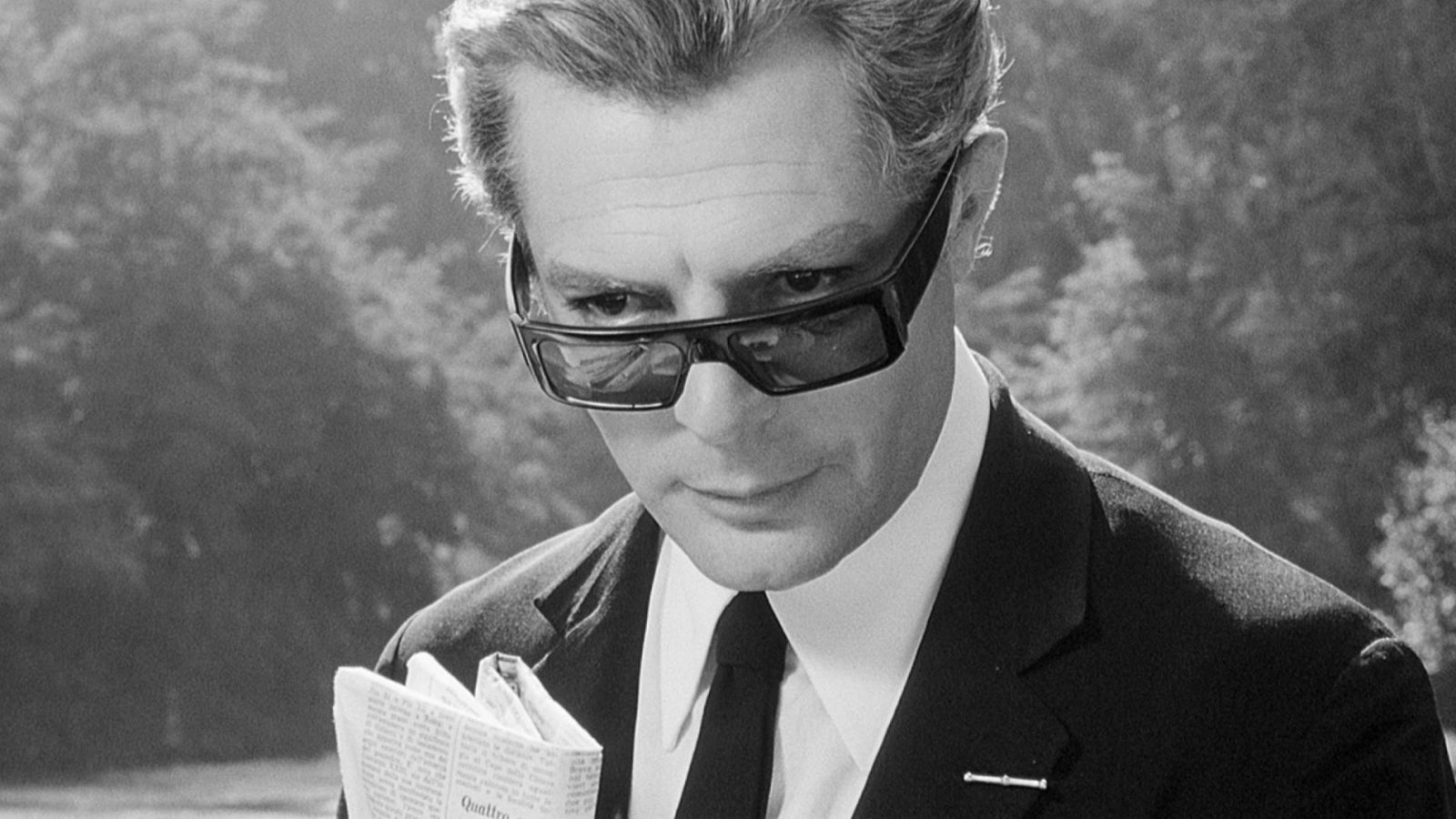

10. Last Year at Marienbad (1963)

Several of the films on this list have gotten analyzed a lot for whatever reason, as it so happens. On the other hand, it is hard to imagine Last Year at Marienbad without analysis and a lot of it.

Last Year was the notable follow-up to French director Alain Renais’ hugely respected international hit Hiroshima, Mon Amour (1959), a much written about film in its own right. Like that film, this one does not give up any secret easily. However, unlike that film with its realistic, rational surface, this one appears to have been designed to be some intellectual puzzle. Even the look of the film suggests some sort of sophisticated game, one hard to figure out.

The basic plot is simple enough. X (the characters have no real names) is sojourning at the elegant (if somnambulant) spa of Marienbad. There he encounters Y, a married woman he claims to have met and loved there the previous year. Y claims no knowledge of any such event, but she might be lying due to the presence of her corpse like husband. X won’t give up and pursues her, with many mind games issuing forth from him.

What does all of this mean? There are many, many writers attempting to answer that one. Is the glass here full to overflowing or has it artfully been created to look that way and, in fact, is completely empty? The film could not have a more composed, controlled look but some are still sure that this is an elite con game and that there is no there there (it was actually given an entry in The 50 Worst Movies of All Time, but that choice lead to much derision).

There was a time when more cerebral film goers gravitated to films designed to feel like a carefully created chess game. The creator of this film never stopped looking adventurous and never took the easy out in telling a story. His films are still being written about and none more so than this one.

Author Bio: Woodson Hughes is a long-time librarian and an even longer time student/fan of film, cinema and movies. He has supervised and been publicist for three different film socieities over the years. He is married to the lovely Natalie Holden-Hughes, his eternal inspiration and wife of nearly four years.