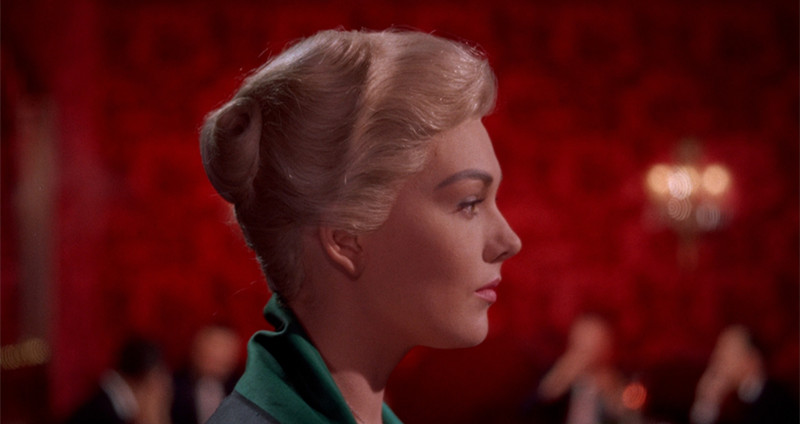

5. Vertigo

Alfred Hitchcock is known for his universally distinctive “hitchcockian” style. Hitchcock has always bellied his films with a sense of mood –especially within the mise-en-scène. Never has he done this more colorfully than in the 1958 thriller Vertigo.

Set in stunning San Francisco, the film follows an ex-police officer played by James Stewart with a debilitating fear of heights attributed by a trauma he experienced on the job. He reluctantly accepts a job as a private investigator for an old friend where he is hired to follow the man’s wife. However, the job becomes increasingly complicated as he descends down the maelstrom of self degradation.

The film’s setting of San Francisco is inherently quite generous in Hitchcock’s endeavor to establish the atmosphere’s presence. The city, in all its undulating glory, already gives the film a great deal of character.

However, what is special about the way San Francisco is framed in the context of Vertigo is how it is construed to be a terrain of inexplicable mystery. Through the unreliable eyes of the unhinged police officer, “Fog City” seems significantly more foggy. Furthermore, the film makes great use of vibrant lighting.

This is especially apparent in the scenes with Scottie in Judy’s apartment. Bright green lighting emits from the neon sign outside the window. The mood in these scenes is in stark contrast with the more idyllic and romantic scenes between Scottie and Madeleine -at the flower shop, the art museum, or where the sun made the waters under the Golden Gate bridge sparkle. In this way, the atmosphere of Hitchcock’s Vertigo experiences the undulation characteristic of San Francisco –rising and falling in and out of decadence.

4. The Mirror

Andrei Tarkovsky’s 1975 drama and semi-biography The Mirror has an impeccable sense of atmosphere due to Tarkovsky’s tactile sensibility, as well as the film’s evocative tone of remembrance.

In The Mirror, Andrei Tarkovsky uses objects as a means of psychoscopy in the film. To clarify, “Psychoscopy” is a term used to describe a psychic ability used to perceive a range of paranormal associations through the touch of an object.

Psychoscopic mediums are frequently called upon to relay the past by holding onto objects and describing the object’s memory. The literary motif has a similar symbology to psychoscopy in the sense that one subject can be used to activate a mythos of meaning.

In film, the editing used to establish the theme within a montage sequence can be used to impose meaning through artful placement of the object within a series of juxtaposing images.

This film serves as a sort of visual memoriam for the life of the character Alexei. The film is a rather literal depiction of life flashing before the eyes of a dying man. Alexei’s memories interlace in a nonlinear narrative where people and places often blend together, coinciding with the omnipresent subjectivity of human memory.

In all of this, specific visual motifs are apparent. For instance, the hair of Margarita Terekhova –as both wife and mother –is given special attention. In service to the film’s overall sense of atmosphere, the ending sequence is certainly most poignant. The timelessness of Maria alongside the preservation of the cabin and field, help realize immortality in the face of Alexie’s mortality. The sounds in this scene contribute to the immersive experience of the film by instilling a moment of realization.

Tarkovsky believed that the aim of art should be to prepare a person for death, “to plough and harrow his soul, rendering it capable of turning to good” (Sculpting in Time). This ideology is exemplified in this final sequence. Soundtrack is also an integral constituent of the closing sequence. The succession of sound, followed by silence, brings about this idea of resurrection or rebirth. Many feel that we cannot return to the places of the past.

Tarkovsky, having to spend the last years of his life in exile, was no stranger to this feeling of estrangement. Cinema, works to grapple with this feeling through its quality of immersion, preservation of memory, and manipulation of time. Ultimately, it is this notion of nostalgia which makes The Mirror particularly atmospheric.

3. Suspiria

As Luca Guadagnino’s 2018 Suspiria adaptation heads to theaters this upcoming November, one can see from the promotional stills that it was the visual reverie of the 1977 Italian Horror film that essentially prompts such a continued interest. Dario Argento, a director fundamental to the Italian giallo genre within Euro Horror, is widely acclaimed for having made the world’s most aesthetically pleasing horror films.

Specifically, his film Suspiria seems to serve as regent amongst his most visceral movies. Set in a beautiful ballet school in Germany, the story follows Suzy Bannion (Jessica Harper) who gets propelled into an atmosphere of ghoulish mystery, mayhem, and murder. Something intrinsic to the film’s character is its very singular setting, as well as its quintessential art design.

Most notably, the film is easily recognized by its gaudy valentine color palette, neon lighting, and hypnagogic infrastructure. A lot of the hypnagogic infrastructure is inspired by the key exterior setting of the Whale House in Freiburg Germany. A gothic bourgeois house in old town, the building imposes the same duality of alienation and beguilement as the film’s art design. Vibrant colors and sharp ornation make the mansion appear like it has been poisoned by lunacy.

Stylistically, the atmosphere poses a threat like any house of mirrors. The carnivalistic dandyism of Suspiria is classic for the Italian giallo genre, based off of cheap yellow paperback mystery novels. Another classic trope of Italian giallo is its aural displacement. Typically these films will employ either soothing lounge music or bouncy synth pop to overpower acts of bloody monstrocity.

In Suspiria, the score is laid out by the prog-rock band Goblin –and it is astounding. The central theme is incredibly unsettling, but also very magical and inviting. The score does a fantastic job of energizing the sense of panic throughout the film, and also coincides with the slasher chase scenes quite nicely. Highly atmospherical, Dario Argento’s Suspiria is a beautiful nightmare to get lost in.

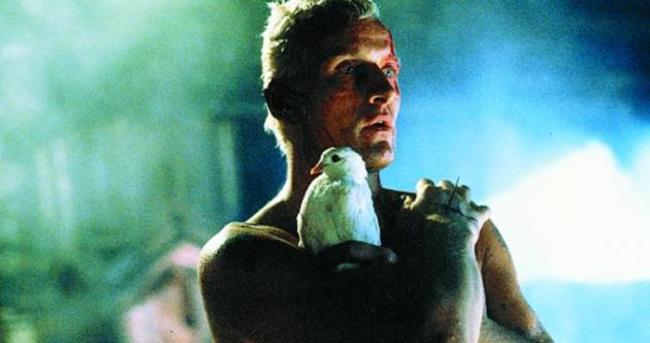

2. Blade Runner

Ridley Scott’s 1982 Blade Runner is set in a dystopic 2019 and is exceedingly atmospheric. Starring Harison Ford, Sean Young, and Rutger Hauer, the story follows Replicant Hunter Deckard (Ford) who is assigned to find and kill four Replicants. Complicating his mission is Deckard’s developing feelings for a Replicant girl named Rachel. Soon Deckard begins to question the moral and ethical ambiguity inherent to his work, as the film considers metaphysical issues of death, souls, and humanity.

Something especially impressive in Blade Runner is the setting. Neon lights blurred by a ceaseless rain, to flying cars which share the sky with smiling holograms –Blade Runner takes you away to a world of technological and capitalistic excess. A world where replicants walk amongst us –more human than human.

Blade Runner has come to define the atmospheric standard of neo noir, tech noir and cyberpunk fiction. It possesses a contemplative atmosphere with dialogue winks to philosophers like Descartes (“I think therefore I am”), while also maintaining a sad sort of nostalgia for a past that we have not lived. This sits in contrast to the ascetic aesthetics that is typical for the dystopian genre (George Lucas’ THX 1138 being a good example of this).

The film also sports a sort of techno-orientalism and an amalgamation of cultures. You’ll see neon mandarin besides a blinking hangul sign, across from some other sign written in Hungarian. The many people all pushed together in a crowd (speaking different languages and seeming culturally severed) creates this feeling of estrangement that allows us to fall right into Decker’s lonely gumshoe detective lifestyle.

The fusion of noir and cyberpunk can be seen in the film’s soundtrack, reference “Tales of the Future” and “One More Kiss Dear”. Blade Runner hosts an atmosphere that feels technologically cutting edge and cosmopolitan, but also has an air of nostalgic sentimentality which breathes life into what could have been another sterile dystopia.

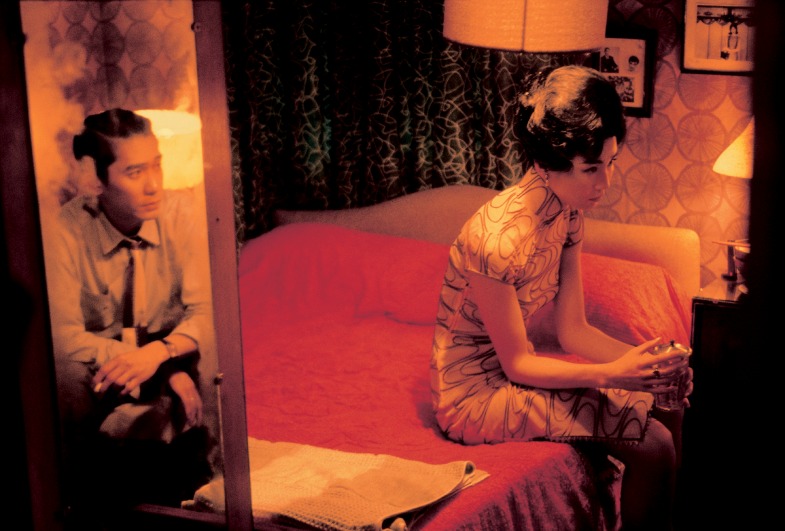

1. In the Mood for Love

Wong Kar-wai’s 2000 romance drama In the Mood for Love is a film with a stunning sense of atmosphere. Set in Hong Kong during the 1960s, the story follows the burgeoning romance between a man and woman who have discovered their spouses having an affair together. The romance is complicated by prying neighbors, as well as their moral and personal repulse for infidelity. Provided this premise, it would seem that the film should be more subdued and introspective. However, In the Mood for Love has a sense of body that feels archly palatial.

The film is heavy with atmosphere, and this is made evident by its visual motifs and soundtrack. For one thing, there is a theme of confinement within the mise-en-scène working to match the suffocating repression of the film’s central romance. The space and shadow in the frames pushes the characters closer and closer together, even though the force is something that the characters are constantly rejecting.

Everything about the film is tight knit, from the apartment interior space, to the community amongst impertinent neighbors. However, the suppression of space doesn’t detract from the texture in the setting.

For instance, fashion also contributes to the notion of atmosphere in the film. Mrs Chan, played by Maggie Cheung, has a wardrobe of qipaos (cheongsams) which are often emphasized in a way that provides a romantic tactile sensibility to the frame. The sharp wardrobe is often juxtaposed with the sooty humdrum of urban nightlife.

Furthermore, the film is also bolstered by a moving and grandiose score –by virtue of Christopher Doyle and Mark Lee Ping Bin. The soundtrack consists of traditional opera, as well as the theme songs from the 1950s serials of Hong Kong. The music, sentimental to the zeitgeists of its time, also informs the eclectic feeling of the film.

As the film closes with an image of the shambolic journalist (Tony Leung), far removed from the bustling streets of Hong Kong, whispering a secret into a hole in one of the stone walls at the ruins of Angkor Wat in Cambodia –the sense of melding between ancient and industrial impulse is apparent. Ultimately, the atmosphere is one that will certainly put one in the mood for love.