5. The Last Laugh – F. W. Murnau

“Der letzte Mann,” released in 1924, was a transitional film in the outstanding career of one of Germany’s greatest directors, Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau, and also a transitional film from the cinema that was learning its potential to the great masterpieces of the late 1920s.

The film is touched by the stylist traits of German Expressionism, with elements such as the shadows taking an important narrative and aesthetic role, but it also has the powerful camera treatment that characterized the films of Murnau. This is a silent film that managed to express the struggle of an old man who is losing the place he used to have in the world.

“The Last Laugh” displays a doorman whose name we never learn, being stripped from his job and his uniform. He’s an old and proud man; the former doorman sees his uniform as the symbol of his honor and decides to keep using the uniform in secret.

Displaying the great understanding he had on film form and his empathy, Murnau created a film in which the psychology and struggles of the characters is revealed not through dialogues or interties, but through visual elements, such as the movement of the camera. “The Last Laugh” is an outstanding film on the suffering of desolation and the passing of time.

4. The 400 Blows – Francois Truffaut

The first film of French New Wave legend Francois Truffaut is also his most acclaimed film. In “The 400 Blows,” Truffaut not only displays his very personal viewpoint on the city of Paris, but also toward childhood and its end.

Introducing Truffaut’s counterpart, Antoine Doinel (a character who would lead several of Truffaut’s film) played by Jean-Pierre Léaud, the film creates a complex portrait of childhood that involves oppressive teachers, ambiguous parental figures, and innocent crimes that lead the path to the freedom of youth. The film, giving continuity to Italian neorealism, introduced to the world a new way of making films – independent filmmaking.

The production scheme of independent filmmaking allowed Truffaut to make the film with a degree of artistic freedom that was needed to create the personal portrait of youth that he wanted. This portrait displays the city of Paris in a much more realistic and less romantic way than previous films, helping to create the bittersweet youth of Antoine Doinel.

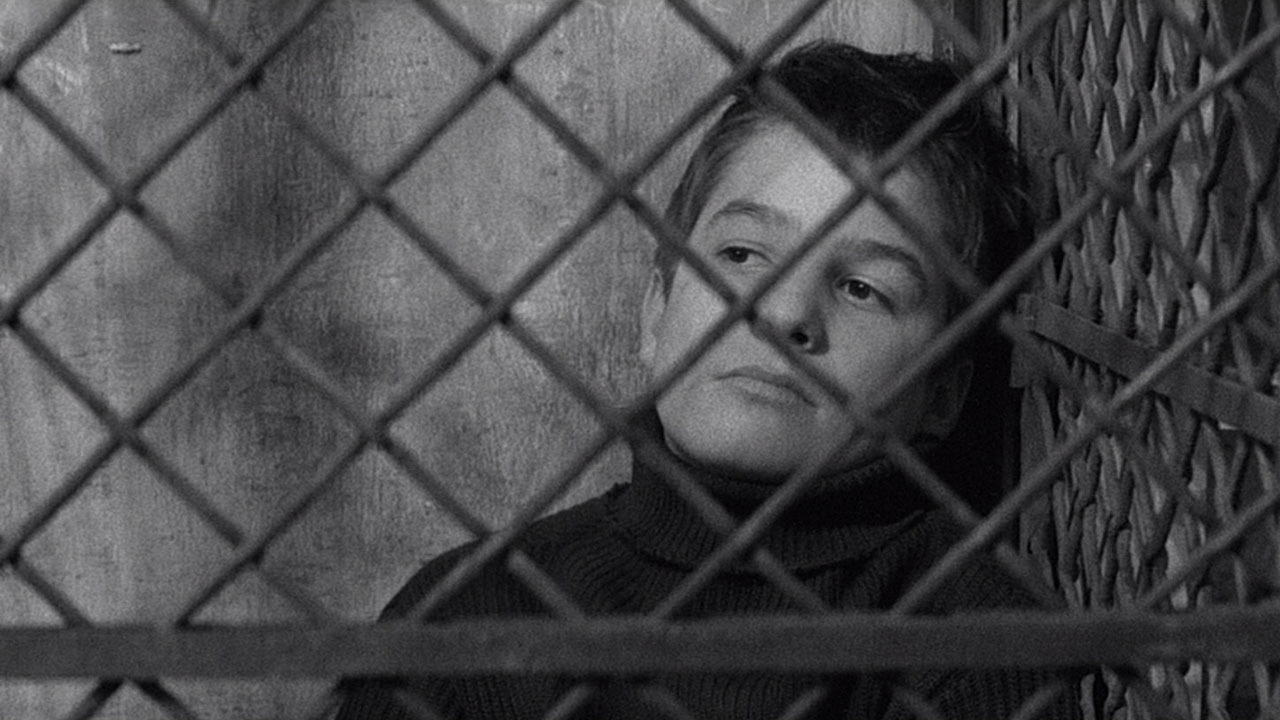

The film displays with a high degree of honesty and complexity the and importance of coming of age. The last scene of the film deserves special treatment due the way it portrays the continuous run of Leaud, becoming a reflection of the whole film, which ends in the freeze frame of Leaud looking at the camera. Freezing the anguish and uncertainty that growing up means for a child.

3. Bicycle Thieves – Vittorio De Sica

In the aftermath of the Second World War, a new kind of filmmaking started in Italy, a country that apart from World War II also experienced the rise and fall of fascism. A cinema focused on complex and real day-to-day characters instead of idealized bourgeois, that treated reality with a more documentary and realistic manner instead of unreal transformations, started with three great filmmakers: Luchino Visconti, Roberto Rossellini and Vittorio De Sica. The three made some of the most moving and humane films in history during the 1940s, and one of these films is “Bicycle Thieves,” released in 1948.

This film displays the struggles of an unemployed man who must find a way to sustain his wife and young kid. He finds a job that requires him to spend the last cash he has on a bicycle, which is stolen on the first day of work. This leads the man to wander around the city with his son in search for the lost bicycle.

Through the journey, the impotence of the father and the implication of this impotence in his relationship with his son is devastatingly portrayed, building up to one of the most moving and harsh endings in film history.

2. Tokyo Story – Yasujiro Ozu

Released in 1953 as “Tōkyō monogatari,” this masterpiece of world cinema by legendary Japanese director Yasujirō Ozu is one of the most beautiful portraits made on the passing of time and its effects on humanity.

This film marks the highpoint of Ozu’s career, when his style was fully defined and when he worked with his great collaborators such as Kogo Noda, Yuharu Atsuta, Chishu Ryu, Chieko Higashiyama, Setsuko Hara and Haruko Sugimura. The film displays an old couple who visit their offspring in the city of Tokyo, where they find that their kids have built their own lives in a changing world that is no longer the one they knew.

The film displays several episodes in the very personal and ascetic style of Ozu, in which the expressive elements are reduced to the minimum while creating moving interactions. The mix of poetic dialogues and contemplation with the moments of kindness allows Ozu to display the humanity of his characters. But as a filmmaker focused on complex character building, Ozu is interested in showing the conflictive nature of human relationships, and in this way the film develops organically and with a conscious perspective toward the human condition.

1. The Grand Illusion – Jean Renoir

Released in 1937, “The Grand Illusion” displays the deep humanism of Jean Renoir and his creative approach toward cinema, for which he became one of the greatest masters in this art. The nostalgic and melancholic portrait of the lives of several French officers while they are prisoners to the German army displays several interactions exploring the humanity in them.

Through the several episodes of the film, we see the prisoners interact with each other in moving moments of frank understanding and kindness. The film has an unusual approach toward war that does not focus on violence, but in the effects of it in human relationships.

The leitmotif of the film is frontiers and thresholds, whether they are due to the national identity of the characters or their condition of prisoners; there is a constant dialectic between alienation and communication.

The film is several episodes in which different people overcome their differences, such as a conversation between captains Boeldieu (Pierre Fresnay) and Rauffenstein (Erich von Stroheim), who build one of the most endearing friendships in film history.

There is also one of the most beautiful romances between a French man who does not speak German (Jean Gabin) and a German woman who does not speak French (Dita Parlo), but who overcome the boundaries of language and fall in love. This is a film that stands as one of the most beautiful relations on human relationships and the frontiers that we built between one another.