Was there ever a title list that so rapidly elicited scorn, anger and even hatred? I think it’s possible, but highly unlikely. Even so, one must stay true to one’s own convictions and intentions or, at the very least, remain open to discussions and opposing arguments (or even an insult here and there but, as Tommy Wiseau would put it, “that’s just life, huh”).

Stating a movie is overrated is an entirely subjective experience, there’s no objective or contestable truth to it, it’s an opinion, like it or not. But don’t get me wrong before starting the list. Saying a movie is overrated if far from saying it is bad.

As a matter of fact, there are several films in this list which are really good, and incredibly important to the history of cinema. They’re just not the almighty second coming of Christ people claim they be. At least not in the writer’s opinion, that is.

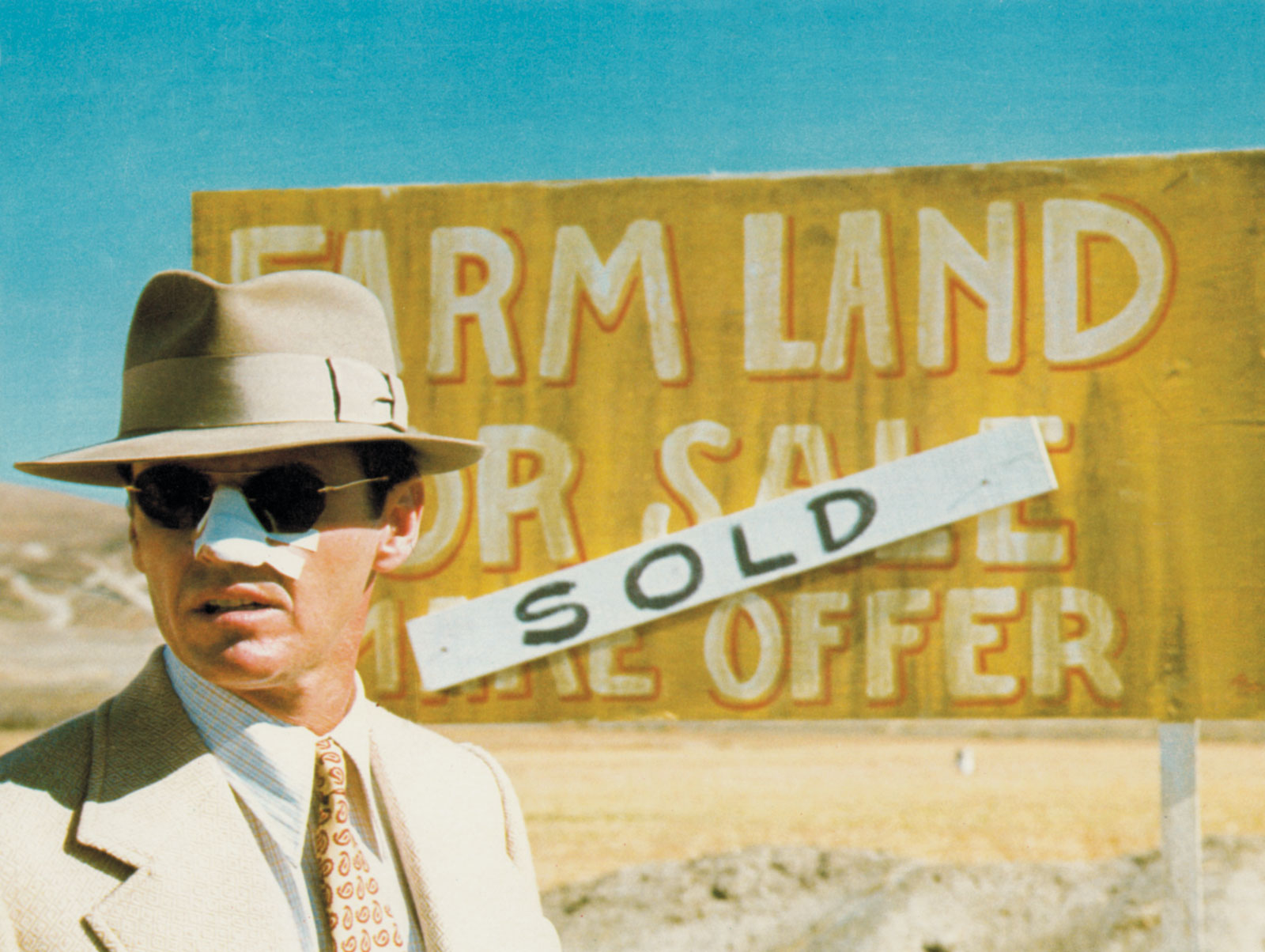

10. Chinatown

Starting the list off with a bang is Roman Polanski’s incredibly lauded “Chinatown”, released to near universal acclaim in 1976. The film chronicles the procedurals of PI Jake Gittes, hired by one Mrs Mulwray to investigate her husband, an executive deeply involved with Californian water reserves. When another woman shows up and claims to be the real Mrs Mulwray, Jake realizes he’s been set up and goes further down the rabbit hole to finish the case.

Sounds like a fascinating plot, right? Who’d have expected the movie would turn out to be the tonally mismatched bore fest it is? But perhaps I’m judging it a bit too harshly. There are a lot of great things in “Chinatown”. From Robert Towne’s remarkable dialogues to the amazing production values, which effortlessly recreates a 1930’s Los Angeles, without mentioning Jack Nicholson’s wonderful performance (the same cannot be said for Faye Dunaway), “Chinatown” is a very admirable film.

But at closer inspection one sees that a lot of characters motivations are so incredibly muddy and borderline bizarre that it draws weight away from the human drama being presented. Characters constantly withhold important information from one another to the point where everyone seems so duplicitous that it’s hard to actually care about any of the protagonists, or about the story which grows more boring by the minute.

Furthermore, while many claim it to be one of Polanski’s greater efforts, his directing is far from memorable here. There’s a distinct clash between his modernist sensibilities and his very honorable attempt at crafting a classic noir film, but it all kind of backfires.

Polanski is a non-classical director trying to shoot a classic movie, and the resulting film suffers from severe identity crisis because of that, as he has no apparent regard for the classic style. Polanski as an auteur never shines through in “Chinatown”, his sensitivity (which would gratefully return in “The Tenant”, a far superior film) is lost throughout much of this contrived story.

The ending is great, though.

9. La La Land

La La Land is a pseudo-musical with uninteresting characters, showy camera work and a screenplay we’ve seen a hundred times too many. Although the film has confirmed everyone’s suspicions that Damien Chazelle is a far better director than he is a writer, he’s still not that wonderful a filmmaker either.

It seems that Chazelle’s proclivity for constantly moving the camera around stems from the fact that his leading actors aren’t really great performers. I mean, look at Ginger Rogers’ and Fred Astaire’s classic routine from “Swing Time”. It’s lovely, elegant and thoroughly impressive. Now look at the camera work therein: it’s simple, it shows what it needs to show and nothing more.

Chazelle constantly does unnecessary camera movements (think the dolly in to see a sunset to immediately dolly out again, or a tilt to show palm trees for the camera to instantly fall back down two seconds later) that makes you wonder just what is he trying to show.

At the end of the day it feels like Chazelle dances with the camera to hide the fact that his actors can’t dance, so instead of making the scene more interesting otherwise he just amps up the Steadicam to 11 and there you go. That’s not to mention the asinine story of a couple who falls apart because of the man’s ambitions getting in the way of love and then the woman gets her break and come on, gimme a break already.

It’s a sugary and showy movie with bland characters and unoriginal story. Fair to say if falls in line with its Hollywood-loving/idolizing concept, but even that – while charming and dreamy – doesn’t quite excuse its excesses

Linus Sandgren’s cinematography is something to behold, however.

8. Moonlight

“Well, if you don’t like La La Land then you definitely like Moonlight, right?”. Yeah, no. Although at first glance it does look like Barry Jenkins will one up Chazelle in terms of wildly inappropriate camera movements (just what is that opening shot), he does take it down a little and is very gracious with his framing and directing, for the most part.

Where “Moonlight” really falls apart, though, is at its screenplay, and especially at its portrayal of Chiron, the lead character. Let’s start with the scripts structure, which looks straight out of a not so great 2-week screenwriting workshop.

The intention in structuring the story about a young boy’s life in three sections (childhood, adolescence, and adulthood) is all very honorable and filled with good intentions, but it’s also quite an obvious and infantile way to architect a plot. The fact that the screenplay pretty much only focuses on the same recurring characters prevents it from developing the story in an unexpected way. It falls prey to its own structure.

But the biggest point of contention to be found regards the constant victimization of its lead character. There’s no effective strength or potency in Chiron, the audience is invited to feel sorry for him all the time. When we’re not pitying him to death, we’re admiring the supporting characters that anchor his life, that keep him going. The character is so impotent it’s infuriating, he has no resolve of his own, no inner fortitude whatsoever.

For how sensitive and careful the movie is in presenting its themes and realities, it’s quite a shame that it all ends up feeling smothered and tame.

7. The Revenant

Man oh man, what to say about Iñarrítu and his penchant for self-importance? Starting from “Birdman” (more on which later), his movies have grown increasingly pretentious and grandiose but without fulfilling its director’s pretentions neither having anything impressive to say/show apart from their undeniable imagistic qualities. But let’s talk about “The Revenant”.

One could make a convincing point for Iñarrítu’s overly long shots and random frames of nature, or even for his heavy-handed comments on the essence of man and his connection with Mother Nature (hi there, Malick) but no one has thus far.

There are no observations (at least not that I’m aware of) on the philosophical ruminations of “The Revenant” or on the concept behind the aesthetical approach to the story, there’s just this overt idolatry of the film’s directing and cinematography (directing, of course, being used only in an imagistic perspective). But most of the aesthetic, albeit certainly incredible and eye-popping, doesn’t feel warranted, it mostly – although there are some exceptions – just looks like overkill. It’s Iñarrítu’s and cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki’s (don’t think DPs can’t get egocentric) onanistic attempt to one up on Birdman and deliver a visually impressive that’s not saying much.

Hey, that’s kinda like Birdman!

6. Birdman

Oh hi, Birdman!

Courtesy of Iñarrítu once again, here comes a story set in the confines of the theater community of New York that attempts to discuss ego, criticism, creative control, narcissism, bad parenting, and a whole other myriad of themes all summed up in one meta-movie told in a single take

Although there is a lot to admire in “Birdman” – some performances are quite good, and there’s an undeniable flair to the aesthetics -, it falls under the weight of its pretentions. Now let’s get one thing out the way. A movie being pretentious isn’t necessarily a bad thing. All movies need to be pretentious to some degree because every film has the pretention of saying or showing something. As matter of fact, all works of art have such pretentions.

We only ever call a movie pretentious when it doesn’t come close to discussing or fleshing out the deeper implications it is presenting. And that’s an opinion regularly leveled against “Birdman”; it has this greater than life approach to art, theatre and cinema (indeed the single shot is used to mirror the continuity of a play, although little attention is given to the fact that the perspective from which we watch a play is a key factor in how we relate to it) and in the end much is left to be properly discussed in an interesting manner. Making your protagonist lash out on a supposedly cynical bitch of a theatre critic might not seem as edgy and analytical as one thinks, it might just turn out to be rather silly and vapid.