To be perfect is to be without a flaw. It’s an old truism that nobody’s perfect (per “Some Like It Hot,” a pretty perfect film itself, though not one to be discussed here). Though there are very absolute standards for perfection in some areas, perfection can also be a subjective thing.

Are there films without flaws? This article hopes to provide an affirmative answer to that question. However, the reader should know that perfection can also relate to what a film’s ultimate idea or goal was, and how the elements put together all contributed to making the notion of perfection possible for these films. Film history is full of pictures that were compromised, flawed by miscalculation, or were the victims of caprices of fate.

The films appearing on this list, happily, were finished as their creators wished and those wishes, in the opinion of very many, were proven to be correct. Not all were big hits and many readers may argue about some components of some of these entries. However, in this quite subjective opinion (supported somewhat by facts), here are 10 choices for cinematic perfection.

1. The Rules of the Game (1939)

Many a film buff/scholar will crow about the cinematically triumphant year of 1939. This great year was a bit more true of Hollywood than a Europe that was then going to war, but that continent did have some superb moments as well. One of (if not THE) the best European films of the year came from the man who had been France’s leading filmmaker throughout the decade.

Jean Renoir was the son of the great post-Impressionist painter Pierre-Auguste Renoir and, thus, had some big shoes to fill and he filled them magnificently. Near the end of a platinum spell of filmmaking in the 1930s, he hit a high water mark both critically and with the public with 1938’s matchless war drama “Le Grande Illusion.” His next project was eagerly awaited, but the populace of France was not pleased with what they got.

“The Rules of the Game” (another enigmatic title indicating the richness of the drama) was taken from a play which was a classic of the French theater, “The Caprices of Marianne,” here updated to modern day. Renoir could see (as could many others) that Europe in general, and France in particular, was headed down a rabbit hole towards catastrophe.

Yes, the fascists were advancing, but too many people who might have made a difference were concerning themselves with social games, deceptions, triumphs and failures which were taking their minds off more important things. Renoir (who himself memorably plays one of the main characters in the film) grafted this theme onto the old play’s structure and, like an alchemist, turned it all into gold.

The lens of the past magnified the components of the present. The filmmaker masterfully started with a character who would seem to be the hero of the piece, uses him as an entrance into the exclusive world of those who populate the drama, and then flicks him away, only to bring him back to supply a powerfully ironic punchline.

Only a master could have done it so nimbly. Renoir was aided in no small measure by a magnificent cast, especially the great French actor Marcel Dalio, who gave an indelible performance as an aristocratic marquis who perfectly represents the hollowness and artificiality of the upper-crust French society of the era.

Littered throughout are marvelous touches, such as the automatons the marquis loves and the all too pertinent play being given during the weekend house party at the grand chateau, which provides the main setting for the film. Film scholars have been picking the film apart and putting it back together ever since.

However, the film hit too raw a nerve for its original audience, which literally tore the theater apart, after which it was cut to ribbons by the disapproving Germans after the invasion and played to less than great reviews outside France until a restoration in the 1950s once again revealed its perfection.

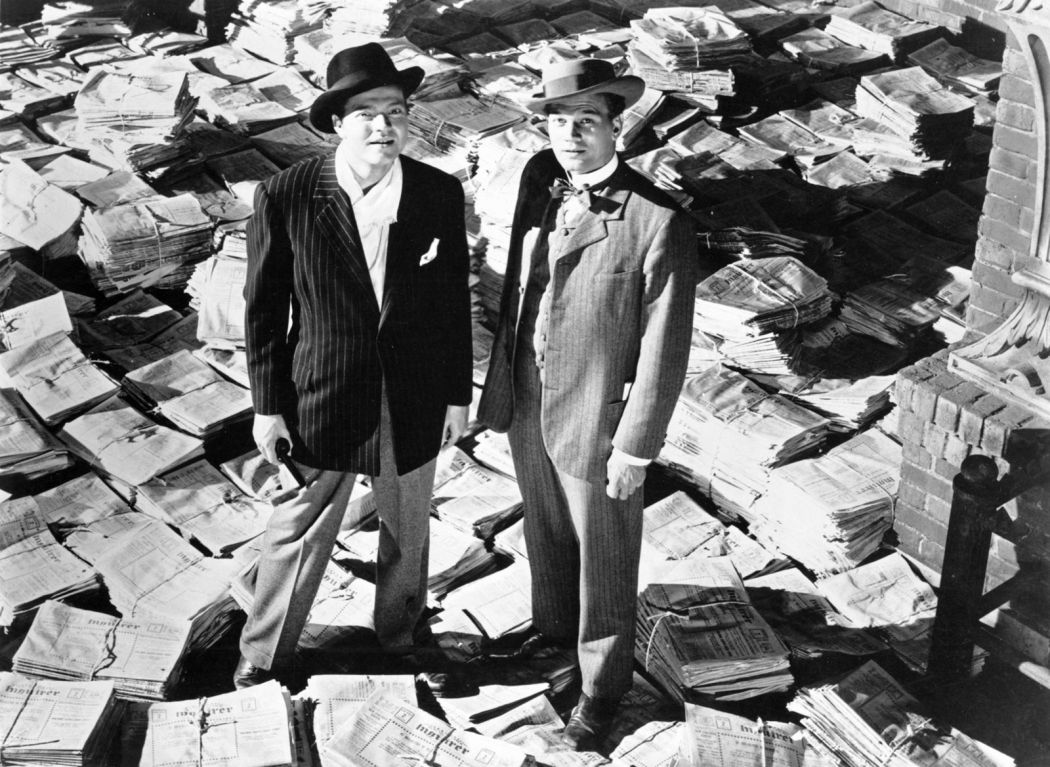

2. Citizen Kane (1941)

Critic Pauline Kael was thought of as an enemy of Orson Welles due to her “Raising Kane,” which threw doubt on the director’s contribution to the film’s script. However, she often praised his work and, in fact, in that very called Kane, “one of the few films of the classic Hollywood era made in freedom.”

This is true, for Welles had been given a Hollywood studio contract that was unprecedented for a rank newcomer (or much of anyone else), which guaranteed him total control over the making of the film and its final edit, provided he stay within a certain budget (sadly, he forgot to ask for this safeguard for his other Hollywood films).

Yes, Welles was full of great and innovative ideas (and some long forgotten ones he resurrected and improved upon), but a huge factor in the film’s making was the fact that no one could say “no, you can’t do that.”

First of all is the matter of the script by Herman Mankiewicz, which would not have been chosen by most of the Hollywood money people and powers that be, if only for fear of offending its inspiration, the daunting press mogul William Randolph Hearst.

Once it was chosen, it was rewritten and reshaped for months thereafter, losing some ideas (in one version, Kane’s son lived until adulthood, only to die leading a crypto-fascist gang in an anti-American raid) and finding others (such as the unforgettable breakfast table montage).

Welles then imported his crack Mercury Theater group (Joseph Cotten, Agnes Moorehead, George Coulouris, etc), each perfectly cast, adding unknown actress Dorothy Comingore (not a great thespian but perfect for the course), and the common but pitiful Susan Alexander, then, he partnered with the excellent and highly innovative cinematographer Gregg Toland, who was given the liberty to perfect his stunning deep focus technique.

Added to this, along with the top-notch craft departments of RKO Studios working at their best levels, was the nine-month editing work of future directors Robert Wise and Mark Robson, making sure that each shot was exactly as it should be. Many think that Welles went slowly downhill after this one, but who else has ever made a film quite like it?

3. Tokyo Story (1953)

If this were a list dedicated to “most perfect directors of all time,” then Japan’s supreme master Yasujiro Ozu would still be included. Not well known in the West during his own somewhat abbreviated lifetime, the discovery of his surprisingly large filmography (which stretched from the 1920s to the early 60s and comprises dozens of titles) has become one of the great delights for many modern film students and scholars.

Most often, Ozu’s great humanity and understanding of the workings of the human heart and the relationships between people takes pride of place in any discussion of his work, and rightfully so. His gifts along those lines are rare in any art form, much less cinema, but it is also noted that he was an excellent formal stylist.

His films, always shot from a low angle (which denotes a seeking of common ground and lack of pride in the culture of his homeland) show that he had a great understanding of artistic forms and compositions. Simply put, while his characters are being profound (though almost always in a realistically subdued way), they are doing so in a very structured (and always creatively appropriate) shot.

Looking over the treasures of Ozu’s oeuvre, it would seem plausible that many of his films could vie for a spot on this list. Oddly enough, though, for many there is only one real choice. When discussions of “the best film of all time” (which often involves the previous entry as well) comes up, the greatly moving “Tokyo Story” is a much noted standout. Cinema often seems to be a medium of youth and speed, so the very fact that this film is greatly concerned with the issues affecting late life is unusual from the start.

The deceptively simple plot focuses on an elderly couple journeying from their home in the country to the homes of their adult children in post-WWII Tokyo.

Though they are not making a point of it, there is a decided implication that this is their farewell visit. Sadly, and all too realistically, their busy children, with families of their own, have very little time for the couple and things of the past in general. Only the widow of their deceased son (a woman also consigned to the distant past by much of the family) welcomes them with genuine warmth.

Unlike most Hollywood films (save for the remarkable anomaly of 1937’s “Make Way For Tomorrow,” which bears many similarities to this film) there won’t be some deux ex machina to bring them all together for a happy ending.

The ending will be all too true to life with the wife/mother dying quietly and the saddened father/husband telling the loyal daughter-in-law to go back to the living while she still can. It’s all unbelievably moving and never feels false or forced. This material could be mawkish or phony but Ozu puts every element, all perfectly chosen and placed, into effect and ends up with a film great in its perfection.

4. The Night of the Hunter (1955)

Depending on how one might wish to view it, classic actor Charles Laughton’s effort to become a film director was either tragically truncated or, through a stroke of fate, short but perfect. After a bad lull in the quality of his films during the late 1940s/early 50s, Laughton was hot on the comeback trail by the middle of the later decade.

During the bad time, he had returned to the theater from which he had come, and not only acted but directed with success (notably the original production of “The Caine Mutiny Court-Martial,” in which he did not appear). He wanted to carry this newfound career over to film. Just as “Caine” was a project he could direct but not plausibly act in, he found a most unusual project for is film directorial debut without a role for himself.

Regional author Davis Grubb penned a most striking novel in “The Night of the Hunter.” The fable-like tale, set along the midwest region of the Mississippi during the Great Depression, involves a murderous psychotic who calls himself “Preacher” due to his religious mania and adoption of the guise of a man of the cloth. He does “the work of the Lord” by cozying up to women with a little bit of money, thereafter taking both the money and the women’s lives before journeying to his next stop.

He fools many adults (especially with the odd love/hate tattoos on his fingers), but his powers don’t work on children. Too bad that he has set his sights on the widow of a man who robbed a bank of $10,000 yet to be found money and, as it happens, the woman has no idea of the money’s whereabouts… but her young son and daughter do know.

This film admittedly does not sit well with everyone. Its story is highly unusual and its style is (not surprisingly) highly theatrical (though not stagey in any way). Laughton prepared very carefully when he took on the project, studying many films from the medium’s history (not something widely done at the time).

Not coincidentally, he chose Lillian Gish, the great star of the influential pioneer filmmaker D.W. Griffith, for the key supporting role of the saintly but pragmatic older woman who appears to protect the children. Gish had appeared quite sporadically in film since the end of the silent era, and it is highly doubtful that any other actress could have portrayed the character so effectively.

The same could truly also be said of Mitchum, a star who had the vibe of a great character actor (one specializing in charismatic villains) and look and charisma of a great star. He, too, was perfect and irreplaceable. In fact, all the roles are perfectly filled (and one may see the documentary “Charles Laughton Directs The Night of the Hunter” to know how carefully the director rehearsed the actors and what happened when they couldn’t come up to standard).

Added to that is the script, written by the superb American author/critic James Agee and adapted further by Laughton, which places everything thematically as precisely as a Swiss watch (the child is always the central image/force of the story). Topping this off are the uncanny visuals and imagery that Laughton puts into virtually every scene (the children’s nocturnal trip down the river is unforgettable).

The critics and public of the time did not appreciate this unusual film and Laughton never directed another. If things had gone differently, might have he been a one-shot wonder, or would the seven remaining years of his life have yielded a few more great films (his unfilmed script for Norman Mailer’s noted novel “The Naked and the Dead” was most promising)? The world will never know that with any certainty, but this one is a known and perfect quantity.

5. Pickpocket (1959)

France’s Robert Bresson was the cinematic equivalent of a fine craftsman who tools everything by hand and makes each piece individual. His films share themes and motifs and his basic, understated methods are alike from film to film, but their surfaces are often quite different.

Like most of the filmmakers represented on this list, it always had to be his way or no way at all. As a result, linking him also with many other great filmmakers, his filmography is small, numbering only about a dozen features (and financing was a major issue in causing this fact).

A Bresson film is intimate in scale, uses no professional actors (and the fact that a few of his “models,” such as Dominique Sanda, chose to become actors thereafter angered him greatly), requires his acting “models” to say their lines as devoid of emotion and bits of “business” as possible, and focuses on sad and brutal behavior with a cinematic “fish-eye,” though not devoid of compassion.

Not everyone loves Bresson films (to put it mildly). They simply drive many crazy (and action/adventure fans are advised to avoid at all costs), but for those who can invest in them, the emotional payoff can be enormous. Many Bresson films might fill this spot (and some may protest the non-choice of “Au Hasard Balthazar” or “Mouchette”), but “Pickpocket” seems to have a special cache.

Somewhat inspired by the great Dostoevsky novel “Crime and Punishment” (though without a murder), “Pickpocket” relates the tale of the title character, a young man named Michel (Martin LaSalle, a non-professional as usual) who is, well, a pickpocket. However, he seems both capable and intelligent in being able to make an honest living, but is also troubled due to a seemingly complex relationship with his dying mother.

There is also the matter of his enigmatic relationship with Jeanne (Marika Green), a young woman who cares for the mother and who seems to be Michel’s conscience. Joining Jeanne in this last matter is a police inspector (Jean Pelegri) who always has Michel’s number, but apparently no evidence in order to arrest him (and the two have a most civil relationship under the circumstances).

Michel lives not in fear of the inspector but with the burden of his own inner voice, which protests his increasingly successful life of crime. The war within builds to one of cinema’s most memorable finales (one which US filmmaker Paul Schrader openly stole, or “paid homage to,” twice).

Looking at the clear, clean black and white images of “Pickpocket,” one has no doubt that what is on the screen is exactly what Bresson wanted to be there. As always with Bresson, he says so little and therefore says so much. There are no big scenes of exposition or overt psychological insight.

There are many deliberate blanks in both the narrative and performances, just as there are blanks in real life. This gives the feeling that the film is showing only a part of a much more complicated whole, just as it often is in life. This and the non-acting work to tremendous effect. Every element seems correctly judged and placed and the end result is surely a perfect representation of what Bresson intended.