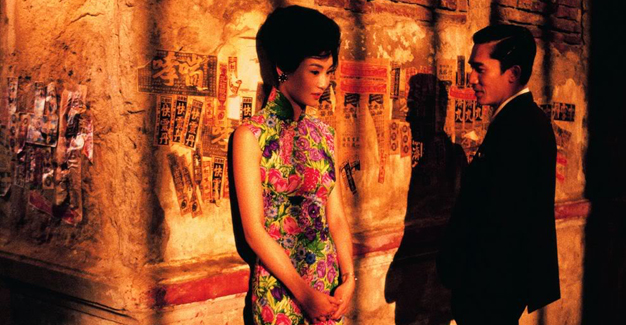

5. In the Mood for Love

Wong Kar-wai’s romantic drama has slowly gestated with us, likely because it is a film that lingers before it aims to punch. The sight of knots in a wall may haunt us, despite the fact that it is not our loss but that of a fictional character. In the Mood for Love is a very real experience that carries the anxiety of our loved ones cheating on us (all while sprinkling pixie dust on the two nervous people and connecting them more than they intended).

The film secretly comments on our double standards of cinematic adultery. We judge the possibility of the spouses having affairs, yet we feel something when the two leads begin to fall in love. How far can a director go with these kinds of characters until we feel ill will towards them? Luckily, Kar-wai goes just far enough, so his film remains as dazzling as can be.

4. Mulholland Drive

Like In the Mood for Love, David Lynch’s surreal masterpiece took a bit longer to become the beloved modern classic that it is today. For Mulholland Drive, the reason has more to do with how real the story becomes with multiple viewings.

We all can piece the story together with enough revisits to Club Silencio, the lot behind Winkie’s, and the audition for The Sylvia North Story. Some of us choose to make sense of this dream more than we do our own; perhaps it is because this cinematic world is available for us at any time.

Mulholland Drive brilliantly combines enough avant-garde elements with mainstream Hollywood tropes to be other worldly. It is a supremely layered neo-noir to the point that you solve the mystery yourself. All I know is that there still isn’t any film like it (not even by Lynch), because there may never be a film that confuses as much as it makes sense like this again.

3. Yi-Yi

What does the title to Edward Yang’s swansong represent? One and one equals two; in Chinese, two is literally one over one. You can see that the ones – on paper – remain separated despite the agreement that this pairing of lines equals two. Life is one continuous flow for billions of people, yet we all have our own pieces to the greater whole.

Following the Jian family (in the form of three different perspectives), we can acknowledge life and death in so many ways within the span of three hours already. The ambitions of one may not apply to another; does love come before work, or is it the other way around? Yi-Yi secretly injects three separate (and brilliant) stories into one picture through the amalgamation of these differing priorities.

It is one of the closest cinematic examples of how we all play different roles in the grander scheme of things. Yang’s final film before his unfortunate passing is a tome of wisdom that nourishes us to the core.

2. No Country for Old Men

It is definitely a topic of discussion when it comes to picking the best Coen Brothers effort. For some – including yours truly – No Country for Old Men may just take the cake. The darkest Coen Brothers film (yes, even more than something like Blood Simple or Miller’s Crossing) is a cat-and-mouse chase between life and death. Death (in the form of Anton Chigurh) chases after Llewelyn, because Llewelyn is a lone wolf that has run off with a briefcase of cash from a cartel crime scene.

Sheriff Bell is not the target of death, because he is a geriatric that has life slowing down for him. Death punishes the young and the old alike, whether it takes away from us too soon or too late. Death itself cannot be stopped, and Chigurh’s many miraculous escapes prove this. Cormac McCarthy’s gothic source material is a struggle with mortality, and the Coen Brothers adaptation is a cinematic marvel that leaves us with much to think about after the crazy chases.

1. There Will Be Blood

We are promised blood, and many of us waited very patiently during Paul Thomas Anderson’s opus (a designation that means a lot, considering his filmography). We become as greedy as Daniel Plainview, as we hope for some sort of large massacre. We get a conman that dupes an entire town into giving him the natural resources he so desires. He symbolically drinks our milkshakes until we are proverbial hollow glasses that are fragile to the touch.

Is there a greater anti-hero in the new millennium than Daniel Plainview? He is devilishly deceptive. We would hate anyone like Plainview in real life, yet here we are drawn to him and his malfeasance. We allow him to get worse and worse.

Sure, there eventually was blood, when the devil himself murdered a man of God, but wasn’t the trip down the well of sin worth it? As we learn from the oil drilling, one sometimes has to drop themselves so low in order to be blasted on top of the pack.