“Philosophical” is a word used so commonly that its definition merits frequent reinforcement. The word philosophy itself is formed from two Greek words: philo, meaning “love” and sophia meaning “wisdom”. As the love of wisdom, philosophy encompasses far more than a collection of personal opinions and intricate mental gymnastics. Asking more questions than it answers, true philosophy is never pedantic and may not always seem profound.

In the same way, a film can be philosophical to the extent that it aspires toward a love of wisdom and inspires in us the same love. A blade of grass may point one toward philosophy as readily a solar system, and a film can do the same, provided that the medium never obscures its message. Many of the great filmmakers have been philosophers at heart who used their craft as a tool to further their own – and others’ – understanding of life.

This list considers ten of the most philosophical films, and suggests a corresponding philosopher whose worldview intersects at points with the movie’s message. Obviously most were not alive during the age of cinema, but if these philosophers had made films, perhaps they would have looked a little like these.

1. The Human Condition

Whose philosophy is best represented by this movie? Leo Tolstoy:

“As soon as men live entirely in accord with [the love] natural to their hearts…and therefore hold aloof from all participation in violence …not only will hundreds be unable to enslave millions, but not even millions will be able to enslave a single individual.”

This 9 ½ hour epic film trilogy by the inimitable Masaki Kobayashi stands as a monumental achievement of both filmmaking and philosophical inquiry. A piercing cry against all war and violence, The Human Condition follows a young Japanese pacifist named Kaji as he struggles to navigate his way through World War II while maintaining his ideals of nonviolence and equality.

Throughout the film’s three parts (No Greater Love, Road to Eternity, and A Soldier’s Prayer), Kaji faces ethical conflicts and harsh punishments due to his beliefs. His struggle to reconcile his philosophical ideals with his honor and duty as a soldier echoes the universal paradox faced by all who aspire to live authentically and consistently. It’s a timeless meditation on the nature of the human condition, and an eternal ode to peace.

Though many remember Tolstoy primarily for his epic novels “War and Peace” and “Anna Karenina”, fewer are aware that he spent the later years of his life as a die-hard pacifist. Though his unfashionable views led to his excommunication from the Russian Orthodox Church, his writings on pacifism had a profound effect on such historical figures as Mahatma Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr. Tolstoy surely would have admired the nonviolent principles of Kaji and supported the peaceful message of The Human Condition.

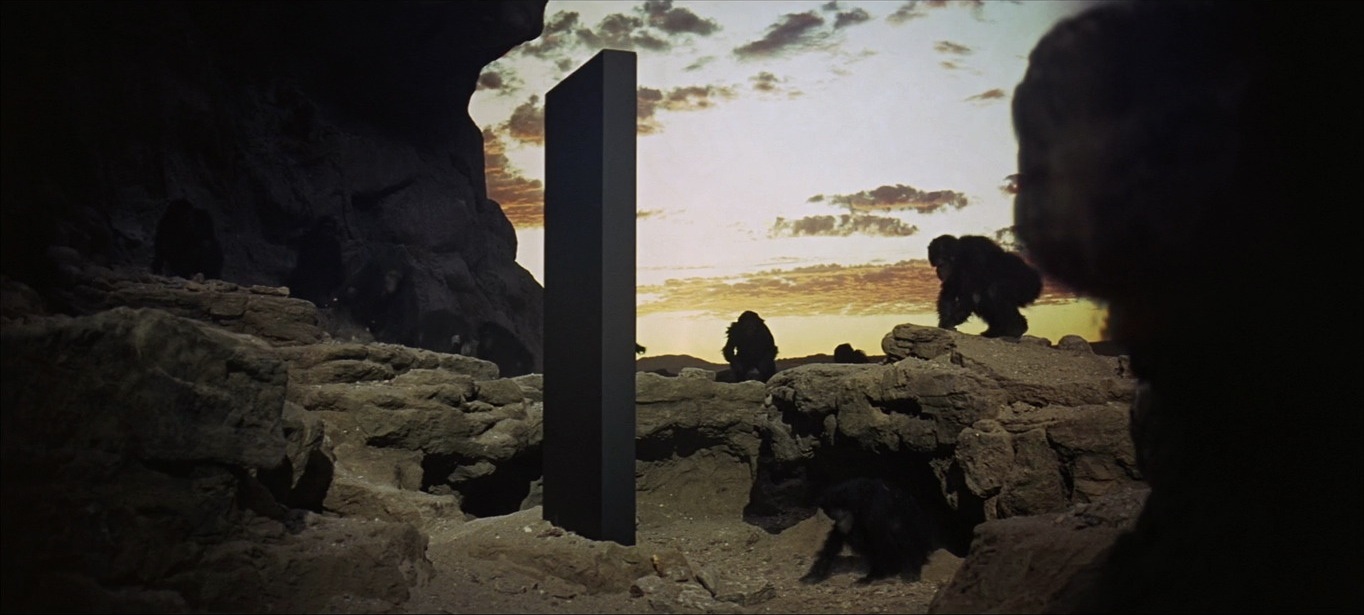

2. 2001: A Space Odyssey

Whose philosophy is best represented by this movie? Friedrich Nietzsche:

“What is the ape to man? A laughingstock or a painful embarrassment. And man shall be just that for the overman: a laughingstock or a painful embarrassment.” “Man is something that shall be overcome…. Man is a rope, tied between beast and overman — a rope over an abyss… What is great in man is that he is a bridge and not an end.”

Bookending this tale of space exploration is a reflection on what humans have been and a meditation on what they might yet become. Following the arc of physical evolution in the film is the evolution of human intelligence from within to without to beyond.

As the earliest primates once discovered the tools needed to survive, modern science has now projected its knowledge to highly intelligent machines independent of human consciousness; from that disassociation is prophesied the possibility that the same intelligence may one day transcend itself and become a truly superhuman entity.

2001: A Space Odyssey has left us with a profound cinematic statement that is at once esoteric and humanistic. The very nature of its vision is sure to keep it perennially relevant and inspiring to future generations.

Don’t let pop culture or superficial summaries convince you that Nietzsche was the patron saint of depression. Far from it – for him, acknowledging hopelessness and despair was only the first step along the road to overcoming those limitations with strength and joy. He surely would have delighted in 2001: A Space Odyssey’s journey from ape to astronaut, and thrilled over its final leap from spaceman to astral entity, with humans as merely the bridge between the extremes.

If further convincing of the parallels between film and philosopher is needed, remember that the movie’s musical theme is “Thus Spoke Zarathustra”, the title of Nietzsche’s magnum opus.

3. Solaris

Whose philosophy is best represented by this movie? Jiddu Krishnamurti:

“What one seeks is the projection of one’s own desire… To seek the proverbial needle in a haystack, there must already be knowledge of the needle… Finding is recognizing, and recognition is based on previous knowledge.” “What we can find by seeking is only the projection of the mind.”

Solaris is the name of a distant planet where psychologist Kris Kelvin has been sent on an urgent, mysterious mission to visit an existing space station. He arrives to find the small crew in a highly unstable state, with one member having committed suicide and the other two in emotional turmoil.

Kelvin begins to suspect strange happenings when he glimpses non-crew members aboard the station, but full panic erupts when his own deceased wife inexplicably appears in his interstellar sleeping quarters. His wife has no idea how she got there, and though Kelvin initially tries to get rid of her, in time he grows reattached to her presence and sets out to unravel the mystery.

Rarely, if ever, did Krishnamurti try to convince his audience of any positive truth; rather, he worked backwards by systematically exposing what was not true until all falseness was dissolved. Likewise, Solaris has no obvious statements to make, but many profound concepts to hint at.

The full nature of the planet Solaris is never revealed, and the puzzling phenomena experienced by the crew are left open to interpretation. But Krishnamurti was forever trying to help people understand how their own social and psychological conditioning colored their perceptions of reality, and he might have found commonality with Tarkovsky’s unflinching examination of the psyches of his characters. This philosopher was actually alive when Solaris was released, and while we may not know if he ever saw the film, one can dream…

4. The Serpent’s Egg

Whose philosophy is best represented by this movie? Hannah Arendt:

“When evil is allowed to compete with good, evil has an emotional populist appeal that wins out unless good men and women stand as a vanguard against abuse.” “The sad truth of the matter is that most evil is done by people who never made up their minds to be or do either evil or good.”

The only Hollywood film by the great Ingmar Bergman has sharply divided audiences ever since its release, but few would argue that its philosophical considerations are not profound. The Serpent’s Egg focuses on Abel Rosenberg, an American Jew living in 1920’s Germany who is struggling to navigate life in post-war Berlin.

As his own alcoholism wreaks havoc on his personal life, Rosenberg begins to suspect far more sinister circumstances unfolding around him in the form of systematic human experimentation and poisoning.

Through his drunken haze, he realizes that the dead bodies piling up around him are more than a coincidence. In fact, the film reveals to us that the secretive killings and torture were funded research by the same parties whose power and evil would explode into the travesties of the Holocaust.

Hannah Arendt lived through the time of the horrific events portrayed in The Serpent’s Egg. Her philosophy and the film’s message in fact go hand in hand as powerful rebukes to the rampant justification of evil and butchery that took place during the time after World War I and leading up to World War II.

Arendt’s writings on “the banality of evil” called attention to and lamented the fact that much of the killing and human experimentation that occurred was done by people who believed that they were doing the right thing, or serving a noble cause. The fact that such tragedy was not stopped in its earliest stages, but rather allowed to ripen into full maturity is a difficult truth examined and mourned by both Bergman and Arendt.

5. Au Hasard Balthazar

Whose philosophy is best represented by this movie? Arthur Schopenhauer:

“The assumption that animals are without rights, and the illusion that our treatment of them has no moral significance, is a positively outrageous example of Western crudity and barbarity. Universal compassion is the only guarantee of morality.” “Man is the only animal who causes pain to others with no other object than wanting to do so.”

Au Hasard Balthazar’s approach to its philosophical themes is brilliantly unique. Director Robert Bresson chose to cast a donkey as the main character, and to follow its life from youth until death. By considering a meek and passive animal, the film starkly highlights the intentional cruelty inflicted by humans on the beast Balthazar throughout his life.

As Balthazar is passed from owner to owner he is the subject of many beatings, and his inability to defend himself seems to draw out the worst impulses in the people who dominate his life. It’s a heartbreaking but enlightening saga that rings tragically true, and forces the viewer to weigh the ugliness of human behavior against that of the symbolically saintly Balthazar.

Few philosophers considered the nature and plight of helpless beasts more than Schopenhauer did, and few wrote forcefully about the morality manifested by one’s treatment of animals. He often compared the virtues of humans unfavorably to those of animals, and would no doubt have recognized Bresson’s’s examples of shameless human cruelty perpetrated upon the meek Balthazar.

In addition, Schopenhauer extolled the spirit of meekness as a trait in animals to which humans should aspire. Bresson’s film and Schopenhauer’s philosophy both point toward humility as a sign of maturity and a spiritual goal worth attaining and maintaining in spite of the personal hazards it may bring.