It goes without saying that a list of only 10 directors couldn’t contain all the great directors that every student or person interested in cinema must take into account so as to have a wider knowledge about cinema, so it’s understandable that there’d discrepancies.

Great directors such as Abel Gance, David W. Griffith, Sergei Eisenstein, Murnau, John Ford, Yasujiro Ozu, Rossellini, Godard, and Howard Hawks haven’t been omitted for their quality or for being considered inferior to the ones in the list, but just to offer to everyone a simplified overview of 10 essential directors that have been always admired and studied.

The reader may realize that the directors included in the list have made their greatest films in the 20th century. We haven’t forgotten directors such as Quentin Tarantino, who is the most-studied director in the UK, neither Paul Thomas Anderson, However, they haven’t been included because when starting to study cinema, we mainly need to go back to the classics.

We’ve decided to include directors who are almost compulsory to study, and, despite the disagreements, have made great contributions not only to cinema but to humanity, giving us authentic masterpieces that have made a great impact on cinema history.

10. Andrei Tarkovsky

Cinematic beauty and poetry are two words that are bound to appear when talking about Tarkovsky. His films are the proof that cinema is art, and art was for this perfectionist director a craving to achieve the paragon. He believed that the aim of art was not to be consumed but to explain by itself the meaning of life and human existence.

That is to say, make people face to the big question: what is the meaning of life? If you want to delve into Tarkovsky’s philosophy, you should read his book “Sculpting in Time” (1986), one of the best-known monographs on filmmaking by a major director.

This beautiful metaphor of “sculpting in time” makes reference to filming; in Tarkovsky’s words, “Film is able to seize and render the passage of time, to stop it, almost to possess it in infinity. I’d say that film is the sculpting of time.”

Tarkovsky is the most important director in postwar Soviet art cinema and one of the most influential auteurs of the 1960s to the 1980s. His cinema is characterized by the metaphysical themes, beautiful and meditative long takes which have been considered by many to be of exceptional beauty, the tendency of framing with doorways, and the great capacity of the director for layering a scene. Since he was a photographer – take a look at his Polaroids collection, “Instant Light” (2004) – we can see he paid too much attention to composition, which is one the most captivating features of his films.

With his films, the director intended to make people find meaning for themselves. Instead of using specific symbols as an object or character, he used the entire atmosphere of which viewers give an immediate response. Here’s a director who masterfully displays the past, the present, the reality, and the dreams creating a magical word, sculpting in time.

RECOMMENDED VIEWING: Ivan’s Childhood (1962), Andrei Rublev (1966), Mirror (1975), Solaris (1982), and Nostalgia (1983).

9. Stanley Kubrick

Stanley Kubrick, one of greatest American directors, masterfully dominated the tracking shot, the reverse zoom, and one-point perspective as no one has ever dominated before. His films are the work of a real genius who wanted to show everything about human facets: love, obsession, history, war, crime, space traveling, social conditioning, science, and technology.

The great diversity of themes could be unified in one single philosophical idea: existentialism. Kubrick used his philosophical ideas, influenced by great philosophers such as Søren Kierkegaard, to create an entire cinematic existentialist universe with some elements of stoicism.

Without any doubt, Kubrick is one of the most studied directors since there’s a huge amounts of linguistic, semiotic issues of adaptation and philosophical approaches to his works. The notable works listed below only shows five of his most known films; however, films such as “Day of the Fight” (1951), “The Flying Padre” (1951) and “The Seafarers” (1953) shouldn’t be neglected if you want to delve into Kubrick’s formative years.

There are numerous studies about his body of work and adaptations from several novels to the big screen. If you’re interested in studying Kubrick’s cinema, get a copy of Gary D. Rhodes’ collection of “Stanley Kubrick: on His Films and Legacy” (2008) in which you’ll find almost everything you need to know about this great director.

RECOMMENDED VIEWING: Dr. Strangelove (1964), 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), Barry Lyndon (1975), The Shining (1980), and Full Metal Jacket (1987).

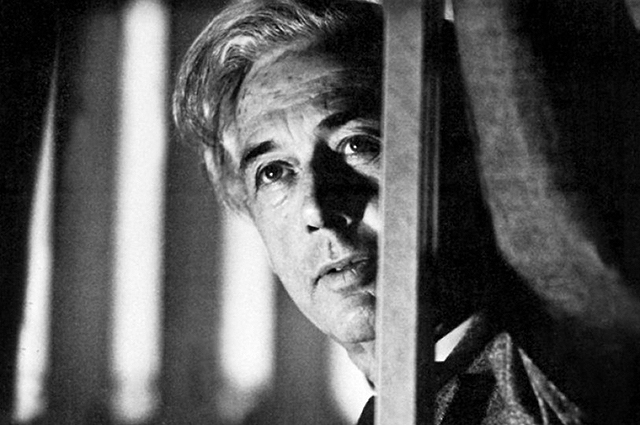

8. Robert Bresson

The well-known French poet and filmmaker, Jean Cocteau, claimed that Bresson was “a special figure in this terrible business of making movies … by his refinement, his senses of ellipsis, his rejection of all excessive effects, his desire to give a fundamental place to construction, he is a classic.”

Although he’s one the greatest directors of the 20th century, he has been overlooked by the majority of cinemagoers. The reason why it’s so is that his films haven’t been widely distributed in the past few years. However, Bresson’s popularity has been growing over the years.

In terms of storytelling, as Cocteau pointed out, he was a classic, and he was only interested in traditional storytelling. At this point, the reader may be wondering why such an unpopular director like Bresson has been included in this list. Lots of books has been written about him and it’s not difficult to find them.

Besides, it should be highlighted that certain aspects of Bresson’s technique put him on this list: his rigorous cutting, his deliberate omissions, his decision to place the effect before the cause, and the powerful idea of building a film “on white, on silence and stillness.”

Here goes an example of Bresson’s sublime technique used in “A Man Escaped” (1951), a film based on the true story of a French resistance fighter, André Devigny, who escapes from a German prison during World War II.

What may call your attention to this films is how the director manages to create a masterpiece out of noises and the absence of dialogue. Diegetic noises on and off camera is a key element on this film that heighten the sense of emotional impact. For instance, the nail-biting escape at the end of the film makes you sit on the edge of your seat with only the sound of crouching footsteps and the distant train. That deserves recognition.

RECOMMENDED VIEWING: Diary of a Country Priest (1951), A Man Escaped (1956), Pickpocket (1959), Au Hasard Balthazar (1966), and Mouchette (1967).

7. Michelangelo Antonioni

Michelangelo Antonioni is synonymous with the notion of art in cinema. When talking about Antonioni, we need to keep in mind that he’s one of cinema’s leading aesthetes, and that his films were a reaction against the reality displayed in the films that were considered to be the ideal. For this reason, instead of being a record of human experience, Antonioni’s films are a metaphor for the human experience.

Antonioni’s meanings hover between the observed reality and the proposed symbol. In “The Adventure,” the head of Anna’s father is linked with the dome of St. Peter’s. This metaphor associates the old man with the old-fashioned structure and tradition.

After watching one of his films, you’ll never watch the simple things of life; for instance, a water tower or plastic dump, with the same unappreciative eyes. If you’re tired of watching the same traditional plots, and you want to enjoy the overlooked beauty of Italy in the 20th century, you could watch, for instance, “Red Desert” (1964).

We could highlight his capacity to show uninterrupted conversations with his incredible long shots. Some may believe the cinematography will make for boring scenes, but Antonioni’s camera movements make him one of the masters of compositions between others like Mizoguchi and John Ford.

His films are very well known for their unconventional visual style, and the numerous and recurring motifs like looking through a window, seeing through fences, framing a character using doorways, and couples walking in the landscapes. Last but not least, another important feature of Antonioni is the use of geometric compositions using vertical, diagonal, converging lines of the setting or the triangular composition made out of three characters in the scene.

RECOMMENDED VIEWING: Story of a Love Affair (1950), The Adventure (1960), The Night (1961), The Eclipse (1962), and Blow-Up (1966)

6. François Truffaut

One of the founders of the French New Wave or Nouvelle Vague could not be missed in the list. He started writing for the magazine Cahiers du Cinéma, founded by Truffaut’s friend André Bazin, in which special attention was paid to great directors who were banned in France during the World War II such as Jean Renoir, Alfred Hitchcock, Orson Welles, Howard Hawks and John Ford.

Truffaut and his friends are known for coining the term auteur theory, in France les politiques des auteurs, a term that makes reference to a film that “has something to say or has certain ideas about life, or cinema or the world.”

Originally, les politiques des auteurs came from the French playwright Jean Giraudoux who said, “Il n’y a pas de pièce de théâtre, il n’y a que des auteurs.” Unlike German expressionism, they were interested in capturing real life, so special attention was paid to the mise-en-scène in order to show an objective view of the world.

“The 400 Blows,” Truffaut’s most known film, is one of the clearest proofs that you don’t need elaborate sets or expensive equipment to make a great film. In the final scene, Antoine Doinel escapes from the reformatory in which he was imprisoned. When he reaches the shoreline, Antoine runs into the sea while the beautiful soundtrack makes the scene even more perfect. The scene ends with a freeze-frame of Antoine, and a zoom in of his face, looking into the camera. What a way to end a film! This semi-autobiographical film, screened a year before Godard’s “Breathless” (1960), was a clear signal that cinema was about to change.

RECOMMENDED VIEWING: The 400 Blows (1959), Shoot the Piano Player (1960), Jules and Jim (1962), The Soft Skin (1964), and Day for Night (1973)