8. Nightcrawler by Dan Gilroy – 2014

A thriller of a kind, Gilroy’s directorial debut was a film acclaimed by critics and adored by audiences as it let emerge a triumphant anti-hero driven by his profit and only that, revealing the razing ethics of new age.

Gilroy spent several years on the screenplay, which was inspired by the biography of the 1940’s photographer Weegee, but extending it to the world of stringers and the topics that prevailed in tabloids and local TV channels in Los Angeles. He was shocked by the fact that violence actually ‘sells.’

People love watching violence that they supposedly loathe. On that he ‘built’ the character of Lou Bloom, an unscrupulous journalist who seeks the most shocking news and will let nothing and no one get between himself and success. Or rather, he will use everything and everyone(‘s life) as a means to get higher.

Jake Gyllenhaal was Gilroy’s first and absolute choice for Lou. The actor was interested in the project from the beginning, and he left any other obligations to work with Gilroy on it. This resulted in a performance that was characterized by critics as tremendous, “A bravura, career-changing tour de force,” and was paralleled with Robert De Niro’s performances in “Taxi Driver” and the “The King of Comedy.”

The film is undeniably a fierce criticism of postmodern journalism, and the audience’s insatiable need for blood and violence that this kind of journalism serves. Gilroy pinpoints the responsibility that people bear in cultivating this kind of journalism. The film was nominated for an Oscar for Best Original Screenplay, and led to other directorial projects by Gilroy.

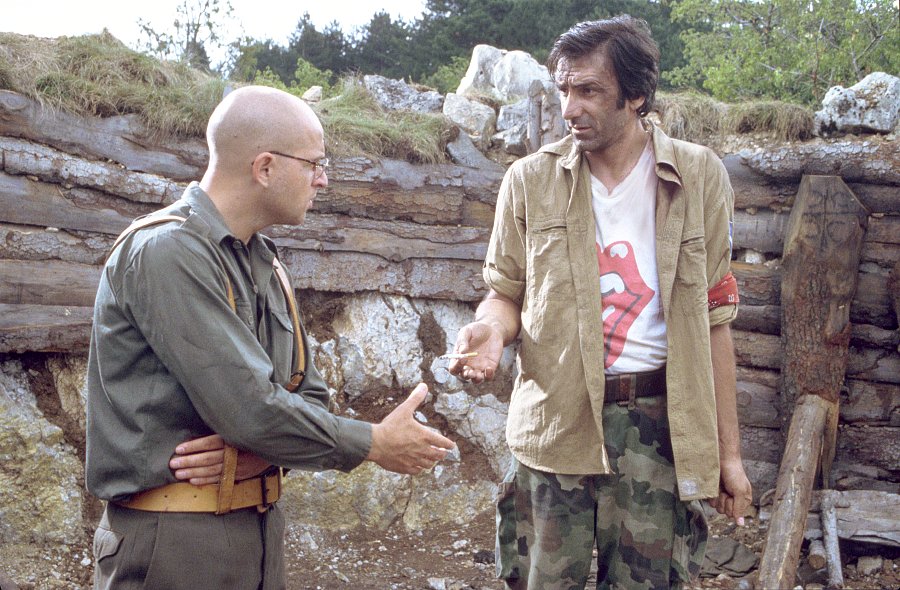

7. No Man’s Land by Danis Tanovic – 2001

The first Oscar win for Best Foreign Language Film for Bosnia and Herzegovina, less than 10 years after the foundation of this country that resulted from the split of Yugoslavia. Danis Tanovic wrote an inspired script and directed a movie that portrays the total absurdity of the Bosnian war – and war in general.

Ciki, a Bosnian soldier and Nino, a Serbian one, both wounded, are in a no man’s land in the frontline. While waiting for the dark, they find Cera, another wounded Bosnian soldier who has fallen over a land mine and cannot move or he will be blown to pieces. The two men wave white flags so that the UN officials would come and help them while an English reporter found on scene brings international coverage to the event.

Small scale stories tell large scale tales. The Serbian-Bosnian war is depicted through its tragic dimensions for all sides in a film that was acclaimed by critics, won an Oscar, won Best Screenplay in Cannes and various other awards, and launched the career of Tanovic. This earned him six more features, three Berlinale and other international awards, membership in Cannes Jury in 2003, and much more.

6. Three Burials of Melquiades Estrada by Tommy Lee Jones – 2005

Very well-known and beloved as an actor, Tommy Lee Jones decided at almost the age of 60 to direct himself a movie. Being a Texan and having just bought a ranch there, he asked Guillermo Arriaga to write a screenplay that would take place in Texas and northern Chihuahua, and he would take the leading role.

The result was ‘Three Burials of Melquiades Estrada,” a neo-western that takes place on the US / Mexico border and addresses the question of borders among countries, ethnicities, ways of life and communicating. The hero, Peter – played by Jones who really enjoyed doing the part – is a rancher who grows very close to undocumented ranch worker Melquiades Estrada, a Mexican who crossed the perilous border and appeared in the opening of a warehouse like John Wayne in “The Searchers.” They work together, they go out together, they flirt and mate together.

When Melquiades is found murdered and sloppily buried, Peter attends the funeral without obsequies and the case is considered closed by the local authorities. Peter tracks down the culprit, Melquiades girlfriend’s stupid and boring husband who works in the Patrol and killed Melquiades by accident, and he forces him to travel, carrying the corpse toward Mexico and Melquiades’ supposed birthplace. So they headed out to the desert wild lands in an initiation journey to Melquiades’ village and the very depth of their own souls.

During his long and successful career, Jones played mostly roles of policemen and military people. When decided to make his own movies, he quite possibly made the kinds of films he loved since he was a kid – westerns. And he did great job. He revived the old western landscape, the arid vast lands with the tall wind-shaped rocks in a totally different social context; Native Americans and Mexicans are not perceived as the enemy, but rather as fellow men to be befriended and honored. Jones has made us, western fans, very optimistic about the future of the genre, as he proved with his second feature that he intends to go on with very innovative westerns.

5. Hunger by Steve McQueen – 2008

“Hunger” was the beginning of a very remarkable career for Steve McQueen. “He’s a genius, and I don’t use light this word,” Michael Fassbender confessed.

It may seem strange that a non-Irish person cast such a clear view in one of the capital episodes in modern Irish history: the hunger strike and death of IRA combatants and their lead figure, Bobby Sands. And he did a great job, showing a lot of respect for history and the people that bear this history. He went with his crew to Belfast to film in the same prison where Sands died; he worked with the Irish people and listened carefully what they had to tell him.

The film is extremely bleak and dark, with scenes of violence beyond imagination. It portrays how living in Maze Prison was that days, how the guardians were trying to dehumanize the prisoners, to what extents the human body may suffer. It’s a film that is very hard to watch. But yet, it is a film to remember.

Two prizes in Cannes and one in Venice was the ‘yield’ for “Hunger,” and McQueen, who made two very important movies (“Shame” and “12 Years a Slave”), won an Oscar and yet there are more to come.

4. You Can Count on Me by Kenneth Lonergan – 2000

Lonergan started with writing (“Analyze This”) to move quickly behind the camera and both direct and write the story of this heartwarming family drama. Well, he played the minor role of the preacher as well and kept playing minor roles in all three of his movies. He proved he has a gift for family dramas, as for all three films he was nominated for Best Original Screenplay, which he finally won in 2017 with “Manchester by the Sea.”

Sammy and Terry lost their parents in a car accident when they were little and had to grew up dealing with the loss… something we suppose happened as the film drives us directly two decades after. Sammy is the lone mother of Rudy. She is working at a local bank branch and lives in their parents’ house in Scottville, a small typical American town in New York. Sammy tries to get along with a boy always asking about a father he never knew, an indecisive boyfriend, and a weird workaholic new boss when Terry appears out of the blue to ask her for money.

Not having seen or heard from him in a long time, Sammy is delighted he could stay with them for a while. Rudy is also thrilled about having an adult male around, but Terry is very far from being the ideal middle class male paragon. Sammy’s life is messed up as her relationships with all the males around her – her brother, her son, her lover, her boss – take rather peculiar turns.

A bittersweet movie with great performances from both Linney and Ruffalo, it premiered in Sundance – it won the Grand Jury Prize tied with “Girlfight” – and was nominated for two Oscars.

3. Lebanon by Samuel Maoz – 2009

Maoz was 20 years old when, serving his military duty, he was sent to fight as a tank gunman in Lebanon’s 1982 war. When he came home, he knew that a part of himself stayed buried there, in the place where he had killed an innocent man without knowing. Many years later, when in 2006 he was watching TV reports from the 2006 war in Lebanon, he decided that the time had come to tell his story.

It took him three years to make a very low-budget movie that is largely paralleled with “Das Boot,” as it gives the same claustrophobic sense of some men who are enclosed in an iron box, having little reaction with the world outside and always fearing that the worst may happen. The only contact they have is the sight of the machine gun that transmit pictures of horror in a war that took place not in the battlefields, but in the towns’ neighborhoods.

The film is literally very dark. As all the shots are taken inside the tank, we can see virtually nothing except of the whites and pupils of the heroes’ eyes, as their faces are all covered with mud or dust or whatever and can be barely distinguished. All that is shown are the eyes, and we have to understand by their expressions what is going on. All we hear are their voices, without knowing sometimes what voice comes from which soldier. Brilliant, inspired shooting!

“Lebanon” was denied by the Cannes and Berlin Film Festivals – for reasons that had to do mostly with boycotting Israel, I suppose, than its artistic level. Nevertheless, the Jury in Venice honored him with the Golden Lion – and a 20-minute standing ovation – that moved him to tears and delighted the Israel government, though I do not understand why. Maoz, though sentimentally linked with the fate of his people, strongly condemns war as a practice for solving problems – something that Israel does so far.

2. Amores Perros by Alejandro Iñárritu – 2000

One of the most successful directors who works in Hollywood today made his debut film just in the beginning of the millennium. It was a really fantastic film that forged the collaboration between Iñarritu and writer Arraya, which gave many remarkable movies.

The story is well grounded in Mexico City, with its poverty and the subsequent high criminality rate, following the lives of three of its dwellers: Octavio, who is in love with his brother’s wife and takes his Rottweiler to lethal dog fights to raise money so he can escape with her and her little baby in a place away from there, even if she doesn’t want to; Valeria, who is a top model in love with an advertising executive, who convinces him to leave his wife and daughters and live with her; and finally, El Chivo, a strange vagabond who lives in a slum together with a bunch of stray dogs and carries death contracts.

All of them meet at the same crossroads, as the frenzied car Octavio drives to get away from his pursuers falls on Valeria’s car, causing her very severe injuries. El Chivo is there too, to pick and heal the wounded Rottweiler.

Everything in this movie goes in a speedy rhythm, everything is needed, and nothing is wasted. The camera moves with nerve from one body to the other, from one story to the other; the soundtrack accompanies those movements and the words are best suited in their places. All the leads are superb as they incarnate the incessant jigsaw puzzle that is Mexico City. The rich and the poor, the glorious and the forgotten, the audacious and the scary all seek love and safety in the way they can. And most of the time they have to face disease and death.

Death is a feature of life that Mexican culture is very familiar with. In his very first movie, Iñarritu was able to define human relations. He was really too good, Iñarritu, filming his own people, his own life. It’s a pity he hasn’t done it again since.

1. The Return by Andrey Zvyagintsev – 2003

Few directors had the luck to see their very first feature film awarded by one of the heaviest prizes in art cinema world: the Venice Film Festival’s Golden Lion. One of them was Andrey Zvyagintsev and “The Return.”

“An epic coming-of-age’ saga,” it has been told, a movie that tells the story of the prodigal Father Otets, who comes home after many years away for undefined reasons, and takes his two sons, Ivan and Andrey, for a trip to the north Russian wild lands. Andrey, the younger, rebels about a parent who never cared.

Otets, the father, sometimes turns really violent toward Andrey, which makes Andrey furious and Ivan even more furious that Andrey will make him lose his father again. When they camp on a remote island in the end of the steppe, Andrey’s doubts culminate, leading to a totally rebellious attitude against his father. He, in his turn, will need to do his utmost to prove that he really loves Andrey.

The cinematography of the film is astonishing. The endless low-plant flats of the Arctic zone, where literally “the sky loves the sea,” endless plains under an endless sky, the absence of noise that gives the landscape a metaphysical tone, the feeling of being at the very end of the world and the limits of human power, the catalytic supremacy of nature.

The story is astonishing, too. Zvyagintsev leaves many details in the fog, just like the landscape he films. When asked about explaining some of these ambiguities, he answered, “I’m afraid there is no clue. You either perceive it or not. There are things which are without answer, and there is nobody who can explain them. Either we feel them and sense them or not.” (Indiewire).

Zvyagintsev’s career boosted and he is now considered as the best living Russian director and, in my humble opinion, one of the most important directors of the 21st century.

Honorable Mentions:

Donnie Darko by Richard Kelly – 2001

Wind River by Taylor Sheridan – 2018

Tangerine by Sean Baker – 2015

In the Bedroom by Todd Field – 2001

Half Nelson by Ryan Fleck – 2006

District 9 by Neill Blomkamp – 2009

Hedwig and the Angry Inch by John Cameron Mitchell – 2001

The Red Turtle by Michael Dudok de Wit – 2016

Matchbox by Yiannis Ekonomides – 2002

From Afar by Lorenzo Vigas – 2015

Chicago by Rob Marshall – 2002

Little Miss Sunshine by Jonathan Dayton – 2006