8. The White Ribbon (Michael Haneke, 2009)

Most of Michael Haneke’s works, from the very beginning, are concentrated on the origins and causes of cruelty and violence (“Benny’s Video” and “Funny Games” are among the most famous). His 2009 Palme d’Or winner “The White Ribbon” is an attempt to map the origins of Nazism; “the roots of evil,” according to him, back in the first decade of the 20th century, just before the outbreak of World War I.

Set in a fictitious protestant village in Northern Germany, it narrates the events through the eyes of an elderly tailor who had worked as a teacher in the village from July 1913 to August 1914, just after the war was declared.

The village is ruled by the strict baron, the puritanical pastor and the vicious doctor, who exert their limitless power upon their relatives and fellow villagers, often submitting them to physical punishments. All of the sudden, strange, violent incidents begin to occur.

The end of the story, which coincide with the start of the war, doesn’t clarify who was the responsible for all of this violence, though it is strongly insinuated that it was the boys and girls of the village who showed an unexpected, revenging cruelty toward both adults and minors.

These youngsters were the generation that led Hitler to power, implied Haneke. A rather naïve approach to the origins of Nazism, I believe. Other societies, with similar structural characteristics, didn’t end up like that.

7. Moonlight (Barry Jenkins, 2016)

The 2017 Oscar winner for Best Picture was a film that beat a lot of leads: the first film with an all-black cast, first LGBT film, and the second lowest grossing film to win a Best Picture Oscar. And it was worthy of it, as it narrates the story of a boy’s life and how brutality changed it for the worst. It tells, in a way, that cruelty creates more cruelty.

It is an African-American story, written by African-Americans, directed by African-Americans about life in the ghetto. It is a story about how being different hurts, in every milieu. It is a story of endless pain and intimidation. It is a story about a cruel coming of age, where no one is there to help in the difficult choices you have to make. It could be the story of many African-Americans and, at the same time, it could be the story of many gay youths.

Chiron has been bullied by his classmates since he was little, just because he was different. His mother isn’t in a position to offer him any kind of help, so when Terrence, a drug dealer, appears in his life, he tries to get from him the love and recognition he so needs.

As a teenager, Chiron discovers that the origin of his difference and the cause of all that pain is his sexual orientation. Being brutally bullied by his classmates, he retaliates in an even crueler way that leads him to a reformatory and then back to the streets, as a cruel drug dealer who knows how to hide every trace of sentimentality he has within.

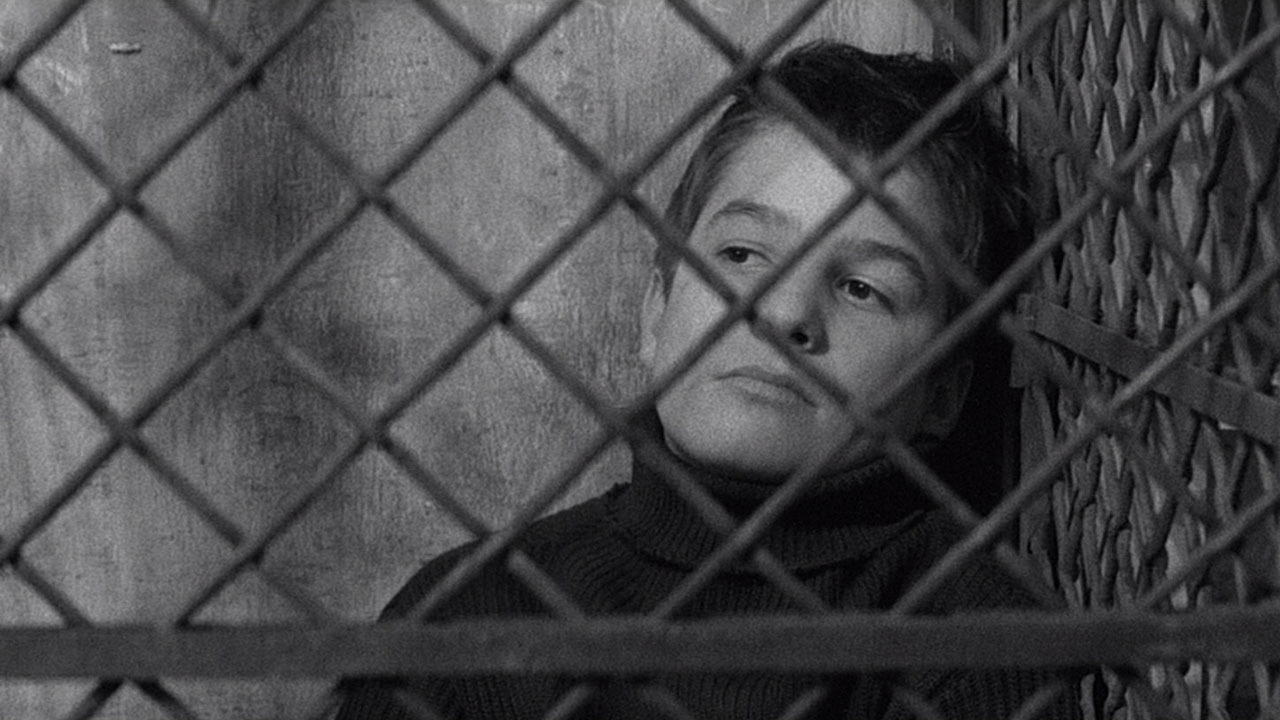

6. The 400 Blows (Francois Truffaut, 1959)

Francois Truffaut’s masterpiece is here to remind us that childhood was not always considered to be an age of innocence and tenderness. Though not depicting acts of violence, the film is soaked in a subcutaneous cruelty, not palpable but felt in every inch of it.

Young Antoine faces cruelty on all levels: a disinterested family, an authoritarian school system, an indifferent surrounding. His only way to attract attention is to be disobedient and insolent, to face life through lies, to commit petty crimes in an attempt to show he is capable of something.

He dreams of the sea and cannot stay still, as movement is a synonym for life, against what parents and teachers believe. All adults are represented as frightening caricatures in a world empty of feelings and meaning.

Antoine’s coming of age is a harsh one. Sent with the consent of his parents to a reformatory center, where he will face more cruelty and violence, he will at last escape and find his way to what he mostly dreamt of: the sea.

5. Kes (Ken Loach, 1969)

Ken Loach’s second feature film is a brutal working class coming-of-age movie set in a mining town in Leeds, somewhere between green fields, factory smokestacks and old and poorly preserved buildings.

Billy leads a bullied life; the son in a dysfunctional family, his father has long disappeared, his mother is constantly looking for a boyfriend, and his brother finds pleasure in galling him. He tries to make ends meets by working early in the morning and then attending school, where both the teachers and pupils bully and harass him. He’s an introverted young boy who everyone believes is stupid.

Billy can only face the cruelty he lives in by finding a creature with which he can communicate his inner world and his love without words. He searches for a baby hawk and trains it, and they form one of the most tender and heartwarming couples in cinema. His love for Kes, the hawk, will even give him the words to communicate with others – and gain attention and care from one of his teachers.

Throughout the movie we witness the incessant struggle of beauty over ugliness, tenderness over cruelty. Billy returns from another nightmarish day in school and plays for hours with Kes, who flies freely around him. His teacher comes to watch and exclaims that it’s the most beautiful thing he has ever seen in his life.

When his nasty brother decides to put a violent end to Kes and Billy’s relationship by killing Kes, it is devastation and mourning as cruelty won over love.

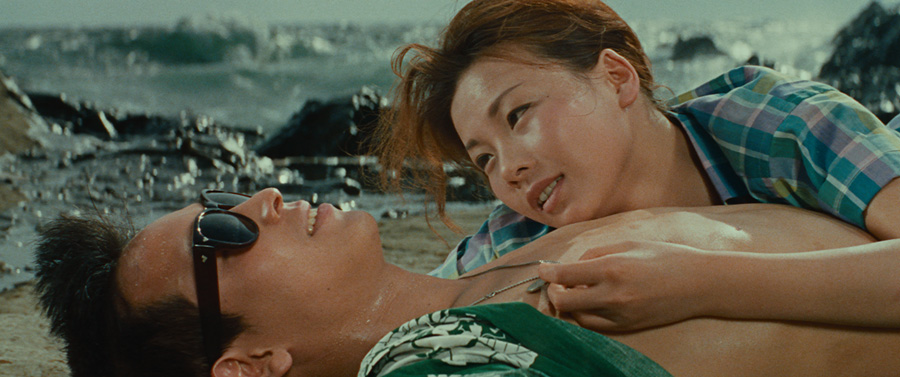

4. Cruel Story of Youth (Nagisa Oshima, 1960)

The second feature film of Nagisa Oshima would have the credits for a place in this list, even if it was only for its title. “Cruel Story of Youth” is cinematographically beautiful and innovative, as it narrates a doomed love story with a tragic end.

Makoto, a young student, gets a lift home by a middle-aged man who then tries to rape her. Out of the blue appears Kiyoshi, who saves her and obliges the man to give them money so they wouldn’t denounce him to the police. They go out the next day and go strolling by the sea. It would be the perfect setting for a heartwarming love story, but it isn’t.

Kiyoshi cannot show but cruelty to the young woman. He forces her to accept lifts by older men and then blackmails them, as this seems the only way he can think to make some money. Makoto, instead of driving away, falls madly for him and moves to his slum, against her sister’s warnings.

The more they get sentimentally close, the crueler he turns toward her, as she never ceases to remind him. The tragic in his behavior is that he too is deeply in love with her, ready even to sacrifice his life for her, but incapable of showing positive feelings.

Oshima juxtaposes this group of youths – Makoto, Kiyoshi, and their friends – with that of Makoto’s elder sister, her husband, and her ex-lover, all of them activists in the 50’s social movement in Japan, who believed that they failed in creating a new and more just world for the younger ones.

That was Oshima’s main concern, which comes out repeatedly in his movies. So in a way, he faces cruelty, this total lack of love and caring emotions, as a doomed heritage bequeathed by the failure to accomplish collective goals.

3. Lord of the Flies (Peter Brook, 1963)

Peter Brook, one of the greatest theater directors of the 20th century, a visionary and pioneer, brings to the screen one of the most classic English novels in a – generally admitted – faithful adaptation, away from studio clichés. “Lord of the Flies” is a masterful study on human nature and the slide to cruelty and violence.

The movie – and the book – is an allegory full of symbolisms. A group of British schoolboys aged six to 14 survive form a plane crash and gather on a tropical island. Ralph, the boy who is elected as leader of the group, tries to organize them as a cooperative society, with rules to be respected.

However, Jack, the leader of a choir group who entered the movie singing ‘Kyrie eleison’ hymns, has a totally different approach. He gathers his own group of hunters and, with the excuse being that it’s them who bring food for the rest, and based on threats about a monster that lives in the island and superstitions about ghosts, manages to gather the majority of the boys in a cave and turn them into enraged irrational savages, who fling themselves into hunting Ralph and the few boys who stayed with him.

This spellbinding film, rooted in theater and literature, having as a soundtrack the rhythm of threatening drums and the screams of deranged children, poses directly the question of whether people, when left free to decide, are prone to the darkest parts of their character, whether human nature tends to incline toward cruelty and savagery.

2. Heathers (Michael Lehmann, 1988)

A college-parodied drama, “Heathers” turned out to be one of the cult 80’s movies that criticized American youth and American society at large. Starring Winona Ryder and Christian Slater, it was “the nastiest, cruelest fun you may have,” according to Washington Post, and earned only two and a half stars from Roger Ebert.

“Heathers” was an iconoclast teen movie that respected no genre norms and provoked fierce reactions by people who actually didn’t want to understand what it was all about. First of all, there was no bad guy in the movie. It was full of ‘bad’ guys. And mean girls as well. Where there was no cruelty, there was just stupidity. And superficial emotions. People who just hang around, not understanding anything about one another. And they are quite content with it. And this kind of attitude, this deliberate lack of any kind of good emotion, is the utter form of cruelty.

And there was the hero. Or rather the anti-hero. An exterminating angel. Literally. He wants to exterminate them all. He is not standing opposite of them – his psychopathy just completes the whole picture. A series of murders, disguised as suicides, led the heroine to a semi-mental awakening that drives her to the solution, the explosive Exodus.

The plot of the movie was considered rather disturbing during the 80s. It turned out to be a bitter reality in the 90s. The main idea behind the script, how egocentricity and a lack of emotions leads to cruelty – and that cruelty is widespread in American society – and how this cruelty will lead to violence, was proven some years later with the flood of mass murders by adolescents that took place in colleges. Jason Dean could be a prophetic portrayal of the teenage sociopaths who massacred American high schools.

And then again came cinema – “Elephant,” “We Need to Talk About Kevin” – to portray reality this time. For its innovative, radical, and finally prophetic approach, it deserves the second place in this list!

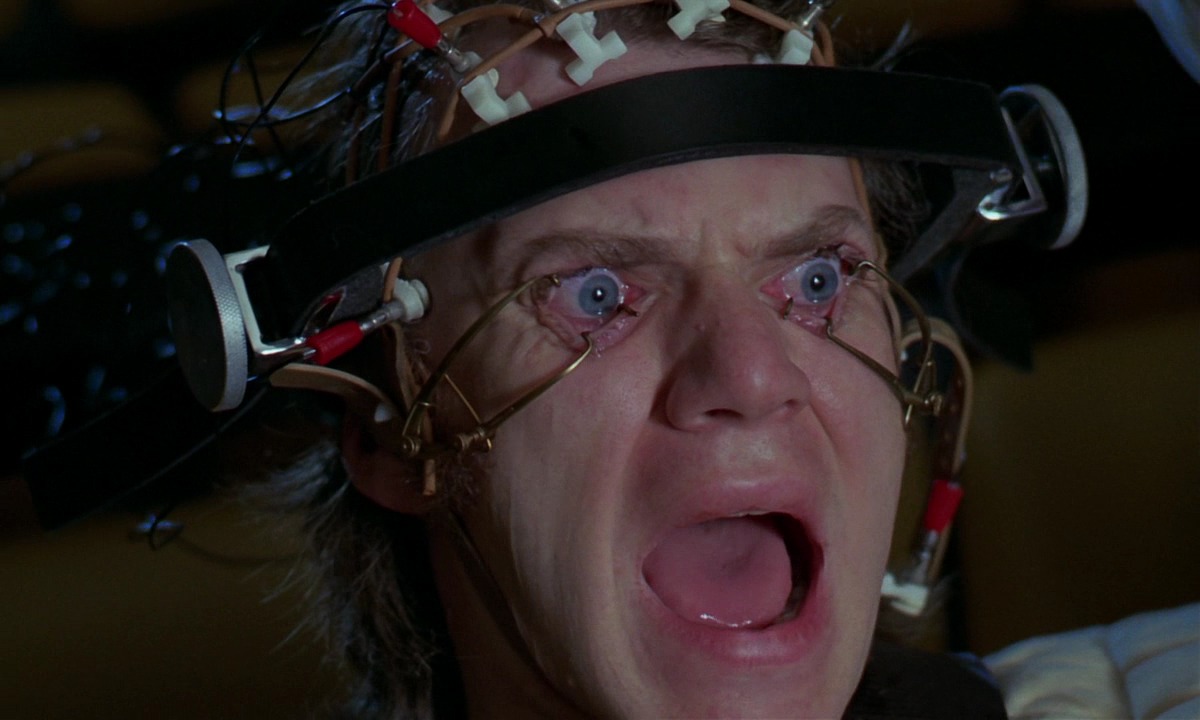

1. A Clockwork Orange (Stanley Kubrick, 1971)

Certainly, no other movie could ever be at the top of this list. Stanley Kubrick’s masterpiece on cruelty and violence, based on the 1962 novel by Anthony Burgess, surprised, puzzled, shocked and disgusted; it was a love-hate relationship for audiences, critics and state establishments.

Rated X in the United States (C ‘condemned’ by the national Catholic Office for Motion Pictures) and accused of being responsible for copycat violence in the UK, it took awhile before this film gained the place it deserved among the all-time classics of 20th century cinema. And it certainly opened up new roads to cinematic depiction of cruelty and (sexual) violence.

What one may write about “A Clockwork Orange” that hasn’t been already written? Let us focus on the negative responses the movie received, especially from Roger Ebert. Ebert didn’t like Alex. He called him a “sadistic rapist” and accused Kubrick of building a flat hero with no motives for his acts. He was trying to seek a social background, a “kitchen sink” drama maybe, a tortured working class anti-hero, and what he saw in “A Clockwork Orange” he obviously didn’t like. Which forwards my thoughts as to what Kubrick was aiming for with this kind of adaptation to Burgess’s novel.

Thus, forwarding, I went from cinema to theater, where I met Bertolt Brecht. He was a genius, just as Kubrick was, no question about it. On 1938 he started writing a play known as “The Good Person of Szechwan,” though his original title “Die Wahre Liebe” (“Love as a Commodity”) denotes a lot. In that play, the role of Alex is reversed: Shen Ten IS a good person who realizes that she cannot live as such, so she creates an evil double of her in order to survive.

Are Good and Evil abstract notions dictated by ethics or religion? Or are they indissolubly tied with the context each society gives to them? What of the alienated societies that create an image of cruelty as lifestyle, and what of those where it is impossible to live without being cruel? What if cruelty is the rule and kindness the exception? What if human feelings and ethics, in this social system, have also turned into commodities?

Alex, eradicated from any social context, offering no apologies or explanation for his extreme cruelty, is a postmodern anti-hero of a futuristic society that terribly resembles the present one.