One of the most common complaints about the films that Hollywood produces is that they present an unrealistic depiction of live. Guy gets the dream girl, guy gets the dream job, guy struggles against overwhelming odds and always comes out on top. Life, on the other hand, often has different plans for us.

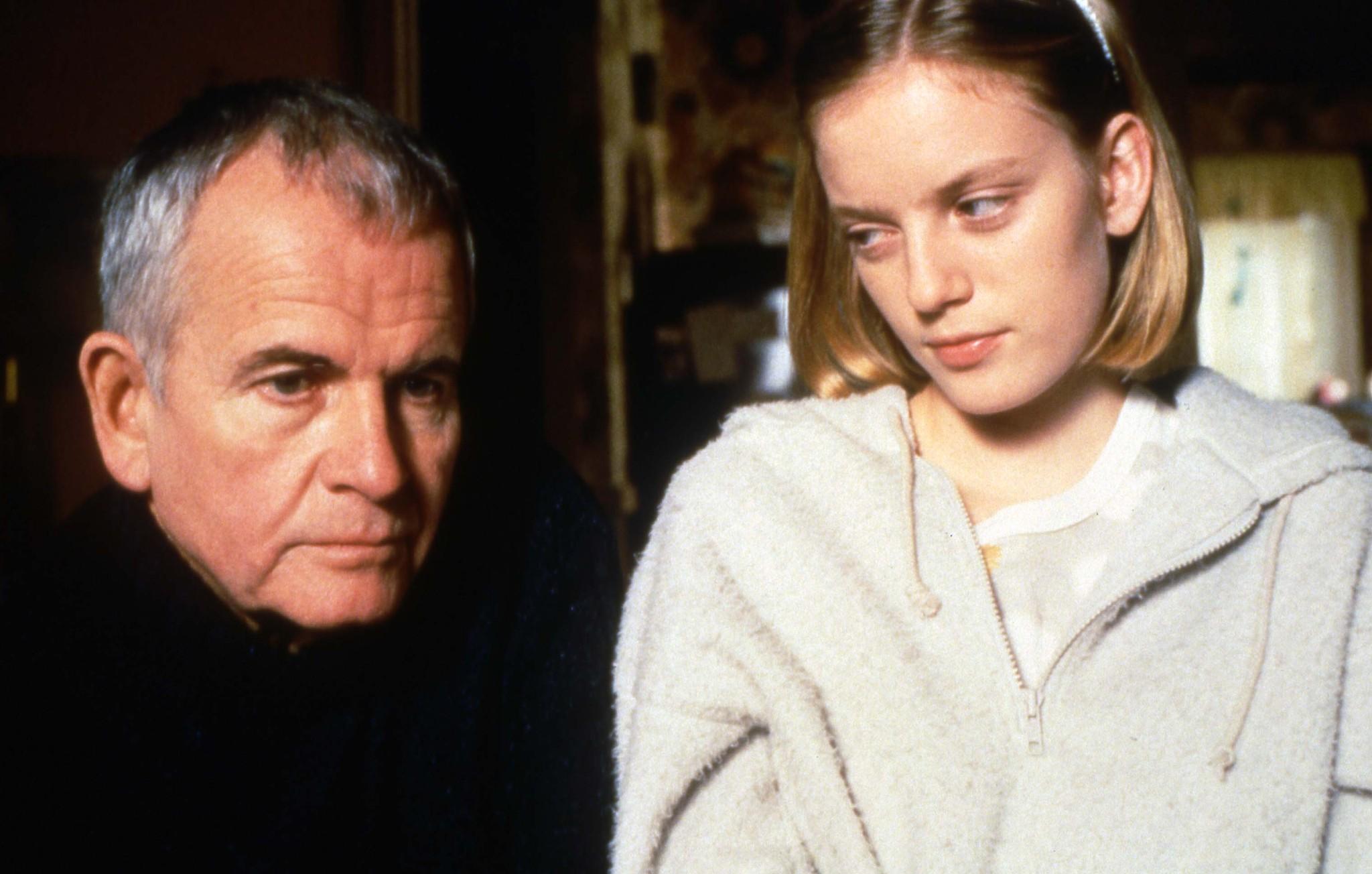

15. The Sweet Hereafter (Atom Egoyan, 1997)

In a small town in British Columbia, a school bus crashes. With the exception of Nicole (Sarah Polley), who is left paralyzed from the waist down, all the town’s children die in the accident. The parents of the town are devastated.

Soon, a lawyer named Mitchell Stephens (Ian Holm) from out of town approaches them, offering to represent them -as well as the guilt-stricken bus driver Dolores – in a class action lawsuit against the manufacturer of the bus. Stephens has his own reasons for wanting to take the case: he has his own complicated relationship with a daughter he has lost to drug addiction, and thinks that if he can make things right with the parents of the deceased children that it might atone for his own sins as a father.

Amid a series of flashbacks, the towns myriad secrets are revealed to the viewer, including the revelation that Nicole, once an aspiring songwriter, was being sexually abused by her own father (Tom McCamus). The tale of the Pied Piper of Hamlin weaves through the narrative, suggesting that poor Nicole thinks she would have been better off with the dead children than she would surviving the accident. For her, death is a relief, and life is far worse.

14. Butterfly Tongues (José Luis Cuerda, 1999)

Perhaps one of the lesser known titles on this list, the Spanish film Butterfly Tongues is nevertheless one of the most powerful entries. Director José Luis Cuerda helm this loss of innocence tale against the bloody backdrop of the political strife and turmoil.

Moncho (Manuel Lozano) is a young boy living in the Spanish region of Galicia during the Spanish Civil War. Due to asthma, he has just begun attending school, where is afraid his teacher Don Gregorio (Fernando Fernández Gómez) will hit him (as is customary at the time).

Instead, the old man takes a liking to the boy, and the two become fast friends, spending their free time searching for butterflies while Don Gregorio teaches Moncho to love learning everything he can about the world.

The Don also forges a relationship with Moncho’s father (Gonzalo Martín Uriarte). Both men are secretly Republicans (“reds”) in an era where the Nationalist factions led by Francisco Franco are seeking to overthrow the government, and must keep their political leanings to themselves. And all goes well, that is, until the Nationalists take over their town. Don Gregorio is arrested, and Ramon – afraid that he will likewise be discovered – burns all of the papers and evidence suggesting he has Republican beliefs.

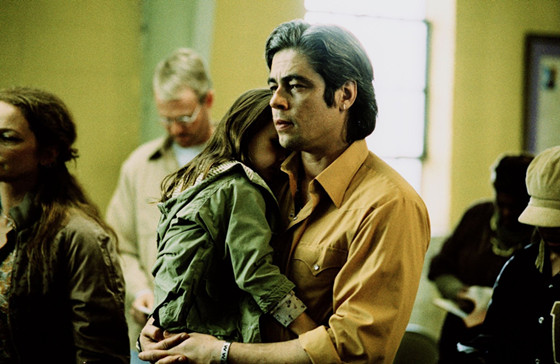

13. 21 Grams (Alejandro González Iñárritu, 2003)

21 Grams follows three individuals and the strange and serendipitous ways in which their lives intersect with one another. Paul (Sean Penn) is a mathematics professor with a fatal heart condition whose wife wants him to donate his sperm so she can have a child in the event of his death.

Cristina (Naomi Watts) is a recovering drug addict now living a happy life in the suburbs with her husband and two daughters. Jack (Benicio del Toro) is a former convict and addict and born-again Christian who uses his faith and experience to turn would-be convicts away from drugs and onto the path of the strait and narrow. Their lives collide one night when Jack runs over Cristina’s husband and daughters, killing them, which in turn allows Jack to receive the heart he so desperately needs.

Cristina, stricken by grief, returns to a life of addiction, and Jack turns himself into the police. But the story doesn’t end there. Jack begins following Cristina, helping her get over her addiction and trying to work up the courage to tell her who he is, while Jack gets out of prison and returns to drug use, having lost his faith. Eventually, the pieces are all in place for these three characters to meet face to face for the first time.

Alejandro González Iñárritu is one of the most influential and renowned filmmakers working today, and yet his more recent and technically polished films like Birdman and The Revenant lack the deeply moving and impressionistic qualities of his earlier works. In 21 Grams, his presentation of the strange and sublime ways in which our lives intertwine make it his best work to date.

12. Terms of Endearment (James L. Brooks, 1983)

Between the Mary Tyler Moore Show, Taxi, and The Simpsons, James L. Brooks shaped and influenced American pop culture in the late 20th century as much as anyone. Lucky for us, he made the transition to film and delivered well-received crowdpleasers like Broadcast News and As Good as It Gets. But none of his work, either in television or in film, has ever been as emotionally wrenching or heartbreaking as 1983’s Terms of Endearment.

To say Aurora Greenway (Shirley MacLaine) is an overbearing mother is an understatement. She prefers her infant daughter cry in her crib rather than sleep peacefully because at least then she knows she’s alive and needing her mother. So when Emma (Debra Winger) grows up and announces her intention to marry Flap Horton (Jeff Daniels), Aurora makes sure to tell her exactly how much she disapproves of the union.

Indeed, Flap proves himself less than reliable when he has an affair behind Emma’s back after dragging her all the way from Texas to Nebraska to accept a teaching position at a state university. Meanwhile, Aurora’s love life takes a turn for the adventurous with the arrival of former astronaut and middle aged playboy Garrett Breedlove (Jack Nicholson, who steals the show), with whom she has a complicated (but never boring) relationship.

In the film’s third act, the story takes a turn for the tragic when Emma is diagnosed with cancer. The final scenes in the hospital, showing Emma saying goodbye to her children as well as Aurora’s grief, are among the most heartbreaking scenes ever put to film.

11. Ali: Fear Eats the Soul (Rainer Werner Fassbinder, 1974)

Of all the filmmakers who emerged in the German New Wave movement of the 1970s, Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s star shone the brightest and burned out the fastest. Other directors in the movement, such as Werner Herzog and Wim Wenders, have gone on to do tremendous work and have long and successful careers.

But they never quite matched the frenzied output by the troubled Fassbinder, whose work totaled over forty films, two television series and a handful of plays and short films in just under 15 years. Among his most famous works is his 1974 film Ali: Fear Eats the Soul, one of the starkest depictions of an interracial relationship as put to screen.

Set in Berlin some months after the terror attack at the 1972 Munich Olympics, the film concerns the relationship between Emmi, a 60-something widow, and Ali, a Moroccan immigrant and “guest worker” in his late 30s. The two meet at a bar, where the servers there mockingly suggest they dance together. They go home, and before we know it Ali has his hand on Emmi’s as they’re sitting on the bed.

Eventually they begin a relationship, but society has other plans for them. Emmi’s children are shocked and outraged by her new beau, with one son putting his foot through the television in a fit of rage. Emmi’s coworkers are at first offended by her romantic pursuits, but soon find a way to “welcome” her into their fold by making it seem as though they’re doing her a favor. All of this racism has a marked effect on Ali, who returns to an old girlfriend one night to eat couscous. Eventually, he develops an ulcer, which the doctor says is “common for men in his position.”

As we live in a world struggling to come to terms with its often horrific past and treatment of others based on purely superficial terms, Fassbinder cuts through the facade of polite society and goes straight for the throat. The experiences of Emmi and Ali are universal, no matter if you’re German or Moroccan, and their simple love for one another provides a small comfort against the prying eyes of a world that refuses to understand.

10. Cries and Whispers (Ingmar Bergman, 1975)

Few directors have plumbed the depths of the human soul like Ingmar Bergman. From Stanley Kubrick to Woody Allen, countless filmmakers have praised the Swedish virtuoso as one of the greatest of all time. Whether he focused on marriage, childhood, trauma, or his own creative process, Bergman never sacrificed his artistic integrity for commercial success, and perhaps no work of his demonstrates this better than Cries and Whispers.

Agnes (Harriett Andersson) is slowly succumbing to cancer. Her two sisters Karin (Ingrid Thulin) and Maria (Liv Ullmann) come to visit her at their childhood home, an old Swedish manor house far removed from the bustle of city life. Despite their prescience, Agnes’ sisters bring her little joy or relief. Maria and Karin seem far removed from the death in the house, incapable of showing empathy or sorrow for the inevitable death of their sister.

Indeed, the only sympathy Agnes receives at all is from her maid Anna (Kari Sylwan), who, having lost her daughter to illness several years prior, understands the pain that Agnes is going through. Much like the old manor house where they stay, the three sisters are beautiful and inviting on the outside, but cold and austere within. And when Agnes eventually succumbs to her illness, the pain is not over, but only beginning.

9. Pather Panchali (Satyajit Ray, 1955)

Turning from Japan to the Indian subcontinent you’ll find another great humanist director from the mid 20th century: Satyajit Ray. Born in Calcutta, British India in 1921, Ray grew up in a family heavily involved in the fields of art and literature. Upon viewing the films of Jean Renoir and Vittorio De Sica, he threw himself into the world of filmmaking, in particular the realistic and humanitarian styles of those directors listed above.

Pather Panchali concerns the lives of the Roys, an impoverished family living in the forests of the Bengal region of India. The father, Harihar, is a priest who dreams of finding success as a poet and spends much of his time away from home. In his absence, the house is tended to by Sarbajaya, the overworked and agitated mother of her daughter Durga and son Apu (who does not appear until later).

The family’s home life is desperate, with their already meager resources being depleted even further by Harihar’s elderly aunt Indir, who steals food from the kitchen. Raising two children practically by herself takes a toll on Sarbajaya, who deals with accusations of theft leveled at Durga and the constant absence of her husband, whose success at becoming a poet is limited at best.

The resulting film is a work of great power, simple and almost bare-bones in its presentation. Ray’s films give us not a camera eye’s observations, but a window into the lives of regular people in some of the most poverty stricken and unfortunate situations imaginable. And yet, despite the oppressive weight that crushes his characters, there gleams a glimmer of hope, a faint light in the darkness that suggests life can, and will, go on.