Since Georges Méliès established the first cinema studio in Montreuil of France, before the 19th century’s sunset, a glowing sunrise was already prepared to take place above the stage of the European cinema. His iconic and determinant “A Trip to the Moon” was a first venturous, resplendent step that blazed a trail for countless cinematic trips.

The following 20th century was defined by lush activity, so in relation to various technological novelties, as in relation to the diverse thematic and aesthetic perspectives that occurred around Europe. During these crucial years, the film industry accomplished significant triumphs, from color applications to montage techniques, while influential film movements were developed, from the early German Expressionism to the brief French Cinéma du look.

Arguably, the charming European cinema of the misty foregone years provides a vintage getaway diode to the past, reflecting intertemporal ideas, panhuman troubles, and inherent emotions. The modern filmic creations, nevertheless, are accurate projections of the contemporary social complexes and our place in them. Shooting several situations and figures in familiar settings, the following 20 films are some of the best films made in Europe during the 21st century.

20. Submarino (2010)

Based on a novel by Jonas T. Bengtsson, Thomas Vinterberg’s “Submarino” at a first shot tenderly focuses on the degenerating effects of parental disdain and early traumatizing events. Two young boys struggle to take care of their baby brother, since their mother has become a fragile downbeat remnant of drugs and alcohol. The premature demise of the unfortunate infant comprises both the divisive and connective tragedy for the wrecked brothers.

The story peers into Nick, one of the brothers, enduring a predestined shady life. Nick’s routine is covered by the severe shadow of his dismal past and destructive childhood, as he wastes himself in alcohol and meaningless sex for the sake of temporary physical pleasure and sentimental disorientation.

In contrast, he perceives his body as an incorruptible sculpture so as to carve in it the ideals he means to keep intact in his heart, while an unattainable woman and a young boy inspire his deepest wounded feelings to resurface and bloom.

Eventually his mother dies. Nick and his brother meet at her funeral, under a bewildering condition of both emotional tension and silent decompression. The nameless brother doesn’t live a satisfying and freed life as well. Following a short period of his life under a chronical prism that emphasizes the chasm between himself and Nick, Vinterberg exposes his restrained psychology and torturing daily efforts for catharsis.

Moving from strictly confined spaces to the harassed details of the protagonists’ faces, and upon a chilling cold-colored palette of time, the dogmatic realism of “Submarino” immerses us into Nick’s detached submarine of misery and abuse. Yet, Nick and his brother have a moment of compulsory contact, somewhere in that deep black abyss of their world.

19. The Lobster (2015)

Yorgos Lanthimos is the representative figure of the New Greek Weird Wave. His films, in their undefinable bitterness and distorted mood, definitely haven’t been created for all audiences. Whether or not you like his style, though, his films won’t remind you of anything else you have seen before on the big screen.

Resembling certain disturbing aspects of reality in a similarly grotesque way as in his 2009 controversial “Dogtooth,” the nightmarish and calmly horrid setting of “The Lobster” is a dystopian sarcastic depiction of social coercive coupling. In a world that dislikes solitary people, single citizens are obliged to stay in a hotel for 45 days, where they are supposed to find a companion, or else they are immediately transformed into animals.

The charmless but placid protagonist, embodied by Colin Farrell, has decided to transmute into a lobster (based on brilliant pragmatic cogitations) in case he fails to find a companion. However, instead of proceeding according to the hotel’s rules, the constant circuit iniquity and arbitrary despotism exhorts David to escape from that paradoxical place of sentimental slavery, and join the lonely humans who survive in the forest.

Facing a new demanding environment that is governed by the chaotic rules of an egoistic and insecure jungle, he realizes that the restrictive social commands are here completely reversed. In an upside-down surface that unlimitedly lies around the geometrically specified construction of his society, David once again is confronted with oppressive parameters that have been formed in order to control his feelings and communicating efforts.

Cerebrally enacting the film’s contradictions and effective illusions through its allegorical narrative, one can sense the repression, sentimental agony, and enforced loneliness of its brilliantly disguised reality. The wide interpretative borders of “The Lobster” allow multiform social analogies to widespread former and current frameworks, attributing to its pitch-black parallelisms a storming honesty.

18. Victoria (2015)

A real-time experiential course that explores a young woman’s psychological profile during a harrowing series of decisions and acts, the technically eccentric German film “Victoria” evolves into a breathtaking psychological thriller of questions, despair, and compassion. Vividly expressed through daring performances and well-crafted narrative realism, Sebastian Schipper’s endeavor to induct his audience into his protagonists’ transparent background serves a flawless result of constant coexistence and sentimental frustration.

She is found in a club in Berlin, dancing to the rhythm of techno music under tactless lights that flash constantly. Victoria senses her loneliness, as she discreetly seeks to find some company. Exiting the club, she impulsively joins a gang of local outlaws. In one destressing take, the camera follows her interactions and induction to the gang, advancing from a naïve blooming encounter to a life-changing criminal activity.

A climactic fragile overstimulation, which fatalistically reveals a dramatic ending, is discontinued by an impatient sentimental externalization. Reluctantly flirting each other, Victoria and one of the boys spend some time in a closed café. She confesses that she can play the piano, while a piano is nobly lying in the empty and dark store. The girl starts to press its keys, and the sound is magical. Her new untutored friend listens to her music, bewitched. Suddenly, Victoria stops and a sorrowful expression swallows her innocent face. It’s then that you know it: she really needs all that horror that looms in the forthcoming future.

Apart from accomplishing a significant technical achievement, “Victoria” is an influential story about broken dreams. The protagonists facetiously claim that they own unobtainable material goods, that they could be prominent citizens, and that they even like the devil. In his overpowering inception, Schipper focuses on lost people who would love to own the world; his characters love the devil, since he liberates instead of establishing rules. By chasing dreams in a ruled world, in one way or another, perhaps your actual pursuits may lie motionless in the cold field of oblivion.

17. Two Days, One Night (2014)

Attempting a double focus on both personal and societal aspects of a contemporary urban issue, the melancholic and at once optimistic film of the Dardenne brothers “Two Days, One Night” observes the brief intense effort of a depressed mother of two, as she unexpectedly succeeds in recovering her mental strengths and springs back from a claustrophobic inner cosmos to the twofold shelter of practicality.

While Sandra utilizes her sick leave so as to rest and reclaim her mind and soul, her bosses at a regional energy plant decide that their company can carry out its tasks without her contribution, and thus her co-workers are offered a fraudulent annual bonus in order to support Sandra’s dismissal. Before she even defeats her longstanding inner demons, the tragic heroine must battle for rights she wasn’t prepared to lose.

A stunning Marion Cotillard, disguised in a mundane costume of a rough demythologizing quality, reels us into a daily woman’s familiar adventure in the unhesitating contemporary industrial world. Visiting all her co-workers one after another, Sandra is confronted with contempt, absurd self-centeredness, and complete submission to the arbitrary norms. Still, she also faces the tender, sentimental, and altruistic aspect of humanity. But substantially, she knows that deep in their core, her efforts were meant to abstain from a catholic status of injustice.

16. Revanche (2008)

Psychographic and massively devastating, Götz Spielmann’s approach toward emotional suffering, revenge, and tolerance, as he projects it on the surface of his film “Revanche,” broadcasts the deepest thoughts and laments of his complex and mentally tortured characters. Calmly weaving a bleak Dostoevskian cloth of mistreatment and suffocating existential binds, the German director posts philosophical questions in relation to moral principles, responsibilities, and atonement.

It’s painfully radiated by his figure: he has a sad life. Sunken into the filthy underworld of Vienna, Alex works for a remorseless promoter and owner of a brothel. His girlfriend, a melancholically charming Ukrainian immigrant, offers her entire beingness to this brothel.

Despite her miserable and fruitless existence, Alex loves her. His hearty, honest, and transcendental feelings for this helpless woman are essentially his only treasure. Thus, after an unsuccessful attempt to rob a bank that costs Tamara’s life, Alex’s solemn aim is to take revenge over her unfair loss.

Constantly looking at a picture of the unfortunate woman, Alex moves to his grandfather’s village, the place where the accident happened, in order to spy on the officer who shot his girl. Robert, the unwitting executor, carries his own heft on the run of a personal underground odyssey. His relentless compunction keeps him awake at night and even immerses him in a living nightmare during the day. Adding insult to injury, his recently detected infertility leads him to an emotional collapse.

Robert’s wife, in her unconscious determinist character and deprived female nature, plays a catalytic role for the story’s connecting points and circular contextual motif. Since she can’t have a baby with her husband, Susanne decides to begin a secret affair with Alex, until she gets pregnant. Her bold sexual approach toward Alex takes him under surprise. Considering it as a part of his revenge, colder than ice, he accepts her invitation.

Their intercourse, standing for the rotten core of their tangled and deceitful microcosm, is distasteful to watch. Alex’s coldness and Susanne’s sufferance emit a mournful, wounded, and abusive sense. While their actions move upon parallel paths of divergence and tormenting inner battles, Alex does nothing more than endure the mistakes of the others, and essentially, the mistakes of himself.

15. Rams (2015)

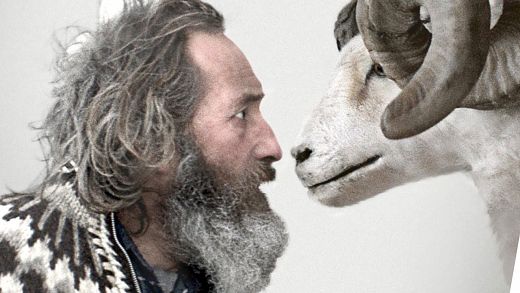

Emotionally rooted in the primal cultural terrain that gracefully survives on the majestic lunar landscape of the Icelandic countryside, two third-aged brothers have willingly raised a chaotic chasm between them, whereas they have both dedicated their long solitary lives to a common traditional and subsistent aim: their precious rams. Praising the unbreakable bonds of brotherhood, “Rams” is one of the most sensitive and effortlessly touching works of the seventh art.

Gummi and Kiddi live silently in the same family-owned field in a small Icelandic village, contributing to the primary provincial economy by breeding sheep. In their remote and insular ethnic sphere, coddling and multiplying sheep is a duty of great social respect and significant financial impact. In this fashion, a local contest is arranged in the village in order to award the owner of the healthiest and most prolific ram.

Kiddi’s best ram wins the contest and as expected, Gummi‘s ego is disappointed. Seeking to prove his ram’s unfair defeat, Gummi takes a close look at his brother’s ram and detects a serious illness that could afflict the sheep of the entire village. Immediately regretting his controversial revelation, the desolate old man realizes that he has to forfeit everything that’s valuable and beloved for him.

Standing mentally paralyzed in front of the demanding and painful outcome of his actions, Gummi keeps a small part of the sheep in his house against the law. Sooner or later, Kiddi finds out his brother’s anomie, and instead of informing on him, so as to take a fairly desired revenge, Kiddi helps Gummi hide the sheep in the closest mountain.

The two men, after 40 years of aversion and juvenile enmity, dare to act as an insoluble unit of gumption, calling to arms all of their remaining physical strength and undimmed sentimental passion for the sake of a common ideal. The brothers make a rough headway on the cold hostile mountain, while local policemen chase them. The night is dark and cold, whispering in their hearts that the battle is lost. Disposing of their wet clothes, they just curl up in a cavity. Once again, it’s only Gummi and Kiddi, having nothing, like in their mother’s warm and protective womb.