Far too much is written in year-end lists about great acting as it forms such an integral, indispensable part of our moviegoing experience. Actors are, at the end of the day, the face of the film. They channel the truth of their characters and express the thematic intentions of the filmmaker seamlessly and in the process, give us cinematic moments of impact and beauty. Their transparent, bare consciousness injects itself into our own, pulsating the emotions of the characters with verve and effect, electrifying the narrative by making us engage with the players.

This decade has already offered up performances bound to have set a bar for great film acting to come and thus, it is not incongruous to list the greatest film performances of the decade so far even though there is still some time to go for the decade to come to a close.

20. Géza Röhrig – Son of Saul

There is a shattering chilliness to Röhrig’s rendition of Saul. It seems cold and distant because in a narrative where the backdrop is provided by the darkest period in human history, it is natural to expect a certain degree of sentimentality and it is hard to discern what part of the performance is manipulation and what honest storytelling. But there is no denying the sheer audacity and stoicism with which Röhrig imbues the one day and a half we know Saul for. It is in no way inauthentic and in its restrained, hardened honesty, it breaks something inside you as it crawls under your skin gradually and with such meagre flair.

Saul is a man constructed by habit and destroyed by fate. We see him walk through his agonizing job with minimal despair or even discomfort. He is been honed to not question life, only to accept it. But when it all comes to a halt when he discovers the body of a boy who after being gassed in one of the chambers is still breathing, the cracks begin to appear on that impassive face. He suddenly becomes endowed by emotion and you mourn for both the circumstances that brought this on him and his haplessness when he simply cannot escape it.

The suspense and the harrowing and immediate threat of being seen or captured is multiplied by the determination and steadfastness with which Röhrig lights up every close up director László Nemes captures with such generosity and delicacy, even when surrounded with such rampant brutality.

Masterfully echoing the fascinating performances in Holocaust dramas like Melville’s “Army of Shadows”, Röhrig has etched himself a spot in the great cinematic cannon of humanist expression in the most inhumane of landscapes.

19. Kirsten Dunst – Melancholia

Lars von Trier does not make films to please audiences – that is perhaps the only thing about his jarring, alarming, disturbing and at times, frankly, horrible filmography that most people agree on. Many find his dizzyingly experimental style heavy-handed and amateurish at worst and unnecessary at best. Others can’t get enough of his admittedly spectacular nose-dive into the darkness of the universe his off-kilter characters inhabit.

Kirsten Dunst’s Justine is perhaps the most human of all them, because his characters might be humane – their tragedies making their disposition sympathetic in the best cinematic sense of that word, but Justine is actually empathetic in all her shaded nuance, so dextrously brought to life by a spectacular Dunst, with that trademark airy effortlessness.

There is a truth with which Justine feels constantly burdened and it blurs everyone around her out of her perspective. She longs for redemption, for finality, for closure, for her deepest fears to either materialize or leave her be. And in the end when she calmly accepts her fate, we watch her simple life pass before her eyes, all her insecurities and misery come full circle, and she can finally taste contentment on her fingertips. It is glorious beyond words.

18. Lily Gladstone – Certain Women

Lily Gladstone was the relevation of 2016 – a performance so deeply entrenched in realizing the reality of the character it seemed invasive to even view it through the lens of the camera. There is such inconsolable, gut-wrenching devastation at the heart of her character’s existence and her longing for company, and for love, that you are almost too overwhelmed to notice the tender joy she experiences in the ranch among her animals.

The Rancher, as she is credited in the film, is a character so sensitively, so poignantly, so affectionately observed and rendered onscreen there is no way for her to not plant her feet in your heart and stand securely there for the duration of the film. Every banal, everyday activity becomes a study in how she overcomes her lack of true, substantial human connection. She is not alone, but when she comes across Kristen Stewart’s law teacher you can tell how she has longed for someone to talk to her, how much she has longed to listen.

In perhaps one of the saddest scenes ever filmed, Reichardt puts Gladstone outside of the law firm where Stewart’s character works, baring her soul to a woman she has barely known for a few days and leaving empty-handed. Life isn’t what fairy tales prepare you for, but in Gladstone’s steely conviction there is consolation for all those who ask for it.

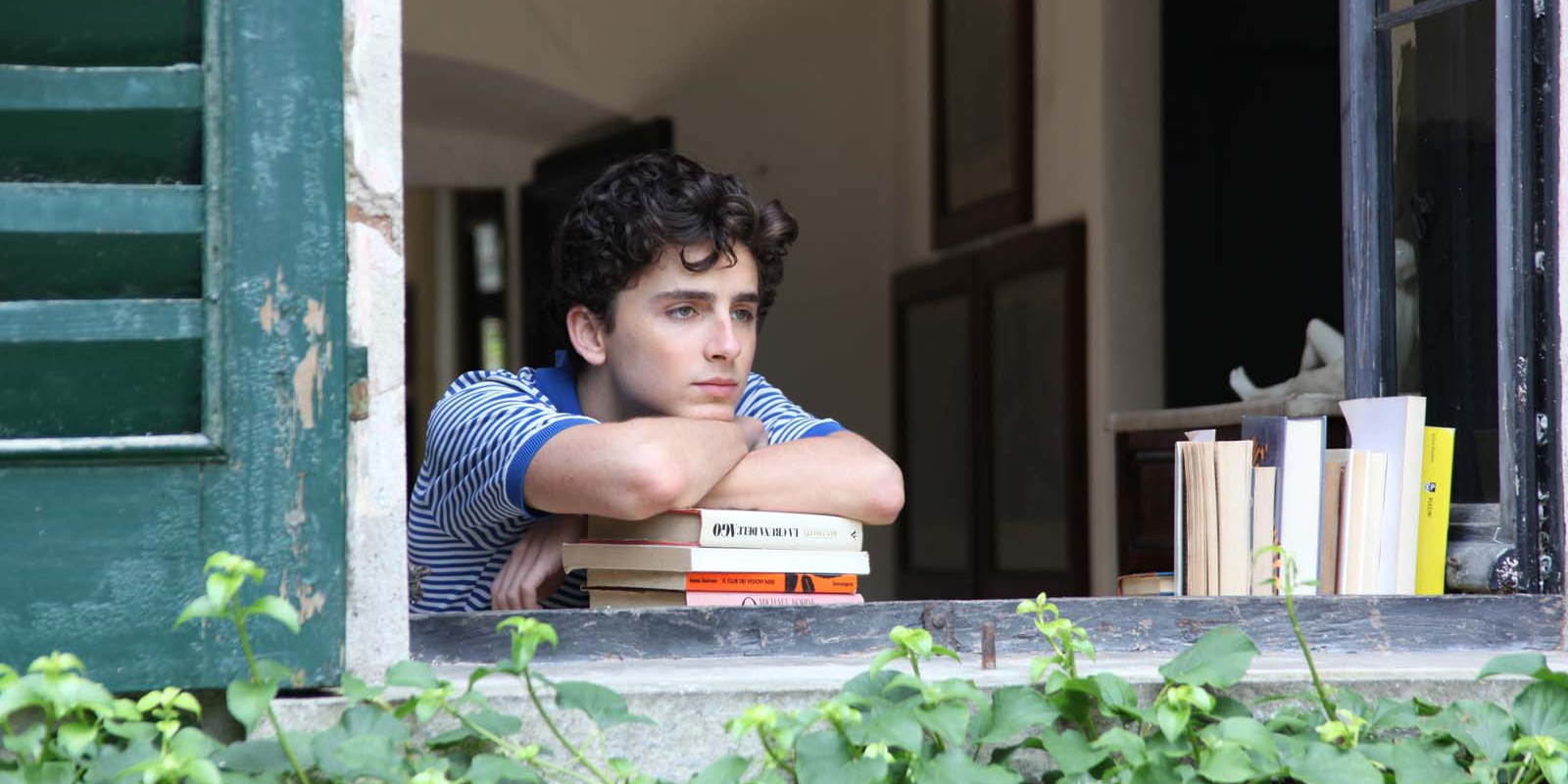

17. Timothée Chalamet – Call Me By Your Name

Whatever you might think of the coyness with which Luca Guadagnino’s swoony, lyrical romance treats its central relationship in comparison to other LGBT films that are unafraid to explore and cherish the sexuality of their characters, there is one thing no one can argue against – Timothée Chalamet’s star turn was one of the most fiercely restrained and elegantly quiet performances of all time.

Like Emma Thompson’s unforgettable subversion of the explosion of feelings her character has on the inside in the impeccable Merchant-Ivory classic “The Remains of the Day”, Chalamet makes another Ivory character iconic by making himself utterly transparent and delicately transfixing.

This is someone who hasn’t explored what it means to be lit on fire with a passion that threatens to consume you whole and yet walks into it with that intoxicating combination of fear and lust and comes out the other side changed for life. His confused, uncontrollable state of mind is so intensely recognizable and so heartfelt that it cannot, but charm you off your feet.

He makes each unspoken desire, each stolen look, and each hurtful realization ache with the kind of authenticity most established actors would kill to possess. Looking into the fire as the credits roll, he walks into your skin and he makes the loss of his character’s innocence and his unhappiness and his contentment with that one summer of his life so beautifully palpable you will be reeling from it for days to come.

16. Rooney Mara – Carol

It is not by sheer coincidence that two of the most essential LGBT performances of all time are placed this close to each other on this list. There is another one higher up, but Rooney Mara’s revelatory work in Todd Haynes’s masterpiece is so effortlessly moving and so inherently delicate that come too close to it and it might shatter into pieces.

Her Therese Belivet has confidence and no shame, but her bringing up has given her no tools to access her truest desires. When she stumbles upon the inflammably charming Carol Aird, played with riotous panache and wisdom by Cate Blanchett, she cannot even articulate what she feels for her. She has no syntax for her relationship with her, because not only is it forbidden, but she has never felt it for anyone else.

And that is precisely what love is like in life. You are isolated from the world, but you are indifferent to that isolation because you are with someone you are meant to be with. When Carol says she always spent New Year’s Eve alone because her husband had other commitments, Therese says she spent New Year’s Eve alone in crowds. She had walked through life never having made a connection, and in their wordless exchange that forms the final crescendo of the film, she finally does.

15. Daniel Day-Lewis – Lincoln

There is not much that can be said about Daniel Day-Lewis that hasn’t been said before, He doesn’t play characters as much as transports their consciousness within himself. He has played real-life characters before to great success in films like “My Left Foot” and “In the Name of the Father”, but never has his impeccable reflection on a historical figure been so in tune with their legacy and the truth of their imperfection or frankly any other actor’s, as it is in Steven Spielberg’s “Lincoln.”

Day-Lewis plays Lincoln’s mannerisms with such command and authority, that you believe that this is how Lincoln spoke and behaved without having the slightest idea of how he did. His stoic, masterful, impassioned delivery of that fiery Tony Kushner dialogue is such a delectable joy – both cinematically pleasing and historically essential.

Wisdom drips off his weathered face, as if he is channelling the genius of the accomplished leader, in almost every frame of the film. It’s not grand, or glorious, and doesn’t aim for such temporary achievements. It’s intriguing, witty and beautifully poised, his voice so calmly reassuring and carrying such weight of its own at the same time.