7. Adèle Exarchopoulos – Blue is the Warmest Color

What would it feel like to bare yourself completely, with no filter and put something uniquely authentic onscreen, something that doesn’t even fit the criteria of a “performance”, because you can essentially feel the actor living the reality of their character? As an audience, it feels intrusive, as if we are invading the space Adèle Exarchopoulos builds around her young, innocent, vulnerable character in this Palme d’Or winner.

Breathlessly her Adèle falls in love with Léa Seydoux’s Emma and tends to her broken heart with the honesty that would make even the most hardened among us swoon. She charts of the course of this vivid, densely layered story with the authority and fearlessness of a seasoned player – one who isn’t aware of their own existence outside that of the character. They are quite simply lost in the search of truth – the truth that will define their characters outside of the film’s narrative sentence and the truth that makes them so endearing while they are onscreen.

Exarchopoulos, along with Seydoux, was a co-winner of the Palme and it is apparent from the very moment we see her as the 15-year old Adèle grappling with her sexuality to the moment she can happily let go and not let that heartbreak that wouldn’t leave her side influence what she has to look forward to. There is hope in her weathered contentment at having lived and loved, and it’s all that’s needed.

6. Cate Blanchett – Blue Jasmine

Any actor would be envious of the sheer range of roles Cate Blanchett has played over the years – Queen Elizabeth, Bob Dylan, Katherine Hepburn – to name a few. She is unabashed in playing her characters’ darker undertones and brings each and every carefully considered subtext to glorious life. But she has perhaps never been as intensely brilliant as she is in Woody Allen’s ode to the tragedy of Blanche DuBois weaved on tapestry of the women who lost the privileged lives they were accustomed to leading because of the financial crisis of ‘08, “Blue Jasmine”.

There is not one false note in Blanchett’s construction of Jasmine – vain, impolite, dangerously delirious and delusional, and ultimately pitiable, and is a master class in how acting can be both deeply subjective and instruct on societal matters with a whip-smart objectivity. She rips apart Allen’s best script in years to shed light on how the world around us can make us compulsive liars and then leave us to our untangle our own webs. How the shine and blitz of high society cannot cure the rot of dishonesty and unhappiness. And how the hole we dig for ourselves deepens on its own even when you stop digging.

In each panic-ridden delivery of luscious dark comedy and each texture of uncontrollable joylessness Blanchett wraps her Jasmine with, we seem to predict her losing it all. And it hurts even more because we could see it coming.

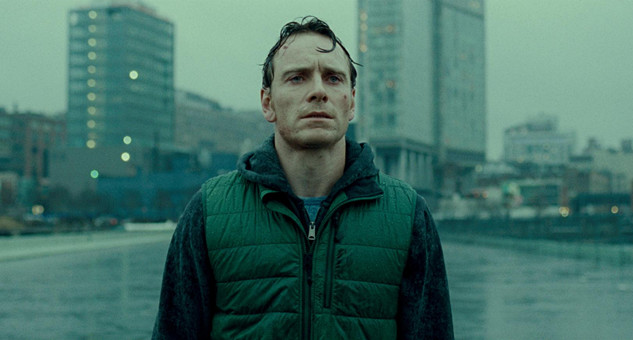

5. Michael Fassbender – Shame

If Adèle Exarchopoulos was laying her soul bare in “Blue is the Warmest Color”, Michael Fasssbender is breaking it into pieces and serving it on a platter for your delight. Delight be damned, there is such unshakeable emptiness in the life of his Brandon Sullivan that it makes you want to weep for his lack of connection with the world around him. He is as lonely as he is consciously isolated.

His cold façade seems unbreakable in the beginning of the film, with his routine, with all its ugly perversions, almost set in stone. It only takes for Carey Mulligan’s Sissy to arrive for Brandon’s life to fall into a disarray he might never recover from. “Shame” makes for cruelly uncomfortable viewing, with the excess of Brandon’s troubles explored fully, with no restraint exercised.

To compensate, Fassbender’s closely knit features don’t break a beat. His expressive face captures each passing moment with intoxicating authority and a riotous humanity. It is hard to look, but once your eyes are locked with his, it is even harder to look away.

4. Emmanuelle Riva – Amour

Emmanuelle Riva doesn’t say much in Michael Haneke’s frighteningly beautiful and bleak “Amour”. All she does is resist and give in, express her pain with the insight of someone who has experienced it herself and relate her despair with anxious, unbearable honesty. You can almost feel Isabelle Huppert’s anger at her father for letting her stay this way, but as her father wisely tells her in a few words, what they share is simply beyond her and our comprehension.

It’s a life lived in a few moments of flipping through family albums and gazing into the eyes of the person you have shared it with. Haneke would never associate himself with sentimentality, but it is impossible to be not moved by how easily we are seduced by Riva (and her worthy screen partner Jean-Louis Trintignant) brining us in the consciousness of their characters with such ease and tenderness. Their end is not happy, but it is with each other, and if you’ve lived in the skin of Anne throughout the film – reeling with her in pain and losing sight of what’s real and what’s not, you know all she’s ever wanted is that.

3. Joaquin Phoenix – The Master

Playing a character in a Paul Thomas Anderson film is like jumping into an alternate universe. Much is unknown and you’re walking into some seriously fatal territory, but as his actors have proven time and time again, if they have the will to explore, they can take the art of film acting and the film itself to newer, unfamiliar heights.

Even this cannot suffice if one were to praise Joaquin Phoenix’s game-changing work in “The Master”. He contorts his body, unwraps the darkest of secrets, and unearths years of pain and hurt as he finds a master who wishes to control him. He is happy to serve him, and his band of followers are content in his control, but Phoenix’s Freddy has survived – damaged and beyond repair – without a master for years and with his sovereignty, he has come to cherish his animalistic existence.

But of course, as he bids adieu to the man who so loved him and the man he has come to love too, he cannot but feel a lack of closure – a memory of a life that will live with him because it never came to fruition. His choice is the right path, but it’s not the one the two lovers want.

2. Isabelle Huppert – Things to Come

While reviewing Mia Hansen-Løve’s “Things to Come”, beloved New York Times critic A.O. Scott asked the question – “Isabelle Huppert – great actress, or the world’s greatest actress?” The answer to that question gets even trickier when you actually see the film and see Huppert craft the life of a simple, level-headed philosophy teacher with such intelligence and keenly observed humanity that it shatters you to pieces.

We all go through change in our lives. Life is, after all, a series of continuing milestones. As Huppert’s Nathalie comes to terms with her separation from her husband, and her children departing to live their own lives and her mother dying, she becomes wise in the perils of detachment. It is freeing and allows her a moment to breathe after decades of being tied up in responsibilities, but it also leaves your future a blank slate.

As Huppert diagrams this fear in Nathalie’s weary, but sharp face, she tells the tale of everyone who has loved and lost, and found life in the hope we hold for the future, for the things to come. As she rocks her grandson in her arms and coos an old lullaby, she is comforting herself too – and in extension, all of us. We will always want to go back to the time we were happy and settled, but being untethered and accepting change has its own charm.

1. Greta Gerwig – Frances Ha

There is not much to Frances Halliday, the eponymous character in Noah Baumbach’s masterpiece. She is wild, immature, reckless and childish. She will never be your friend, and if she’s your cousin or sister you will not be in touch with her. If she is a workplace acquaintance, she will probably eat her lunch with the crazy hipsters or all alone, but never with you. And all of this is probably because she is one of kind, but also completely and utterly like all of us.

Greta Gerwig, who co-wrote the film with Baumbach, makes each moment of Frances’s stumbling, confused, futile existence essential viewing. It’s funny, yes, to watch her ask if “Puss in Boots” is still on while she’s on a trip in Paris, instead of relishing the beauty of the city, but also saddening to see people considering her a thing of the past – something they did when they were in college.

Maybe Frances never left college, and it is hard for her to find her feet in the world outside – she even goes back to her college for a summer job – or maybe we all have stopped taking care of the part of us that is Frances – unabashedly demanding of her best friend, but also intensely romantic; hopeful yet aware of her insecurities; gives big hugs and greets you with “Ahoy, sexy!”; going through an existential crisis way too late, but has a plan for the next few days all set out. Maybe Frances is something we were, and can now only long to be, and our only solace is that Greta Gerwig has painted the Frances we all were to perfection.