10. Memories of Murder (2003)

Bong Joon-ho (2013’s Snowpiercer) rose to international fame, as did his lead actor Song Kang-ho, in this startling South Korean thriller. Made all the more bone-chilling as it is based off of actual events, Memories of a Murder begins in the autumn of 1986 when a woman’s body is discovered in a field outside of Hwaseong, a city fringed by bucolic fields and farmland. Local detective Park Doo-man (Kang-ho) is out of his depth with the brutal crime––soon to be the first of several––and his bungling, ill-equipped team are soon bolstered by Detective Seo Tae-yoon (Kim Sang-kyung) from the mean streets of Seoul.

The film, a favorite of many auteur-adoring critics and filmmakers alike, including Quentin Tarantino and Guillermo del Toro, is wonderful and wise mixture of police procedural, detective film, black comedy, and social satire. It’s an elusive, at times frustrating film––the real-life crimes and those in the film never get satisfactorily solved––Memories of a Murder is one of the freshest and most formal serial killer films around, with enough surprises and shocks to keep viewers riveted and rattled until its final polished frame.

9. The Vanishing (1988)

George Sluizer’s Dutch chiller is a tightly wound, harrowing ordeal that’s full of cruel twists and startling surprises.

Adapted from Tim Krabbé’s novella “The Golden Egg”, The Vanishing fixes its bleak gaze upon the disappearance of Saskia Wagter (Johanna ter Steege), a young woman last seen at a service station with her boyfriend, Rex Hofman (Gene Bervoets) while on vacay in France. Soon it becomes Rex’s obsession to discover the fate of Saskia, and as the years go by, his idée fixe becomes all consuming, and shockingly, his troubles have only begun.

The Vanishing’s uncompromising finale boosts it into the upper echelon of Hitchcockian horror to be sure, but the film as a whole also functions as a master class in unsettling moments and slowly ratcheting terror as Rex hunts the slyest of serial killer.

An intellectual thriller of this ilk is rare, that it conjures equal measures of cursory family life and detached doom with such shrewd elegance resulting in one of the most ferocious climaxes of any film ever buoys The Vanishing into the sinister celestial. So much so that Stanley Kubrick famously and enthusiastically said to Sluizer that he’d watched his film three times, adding it was “the most horrifying film I’ve ever seen.”

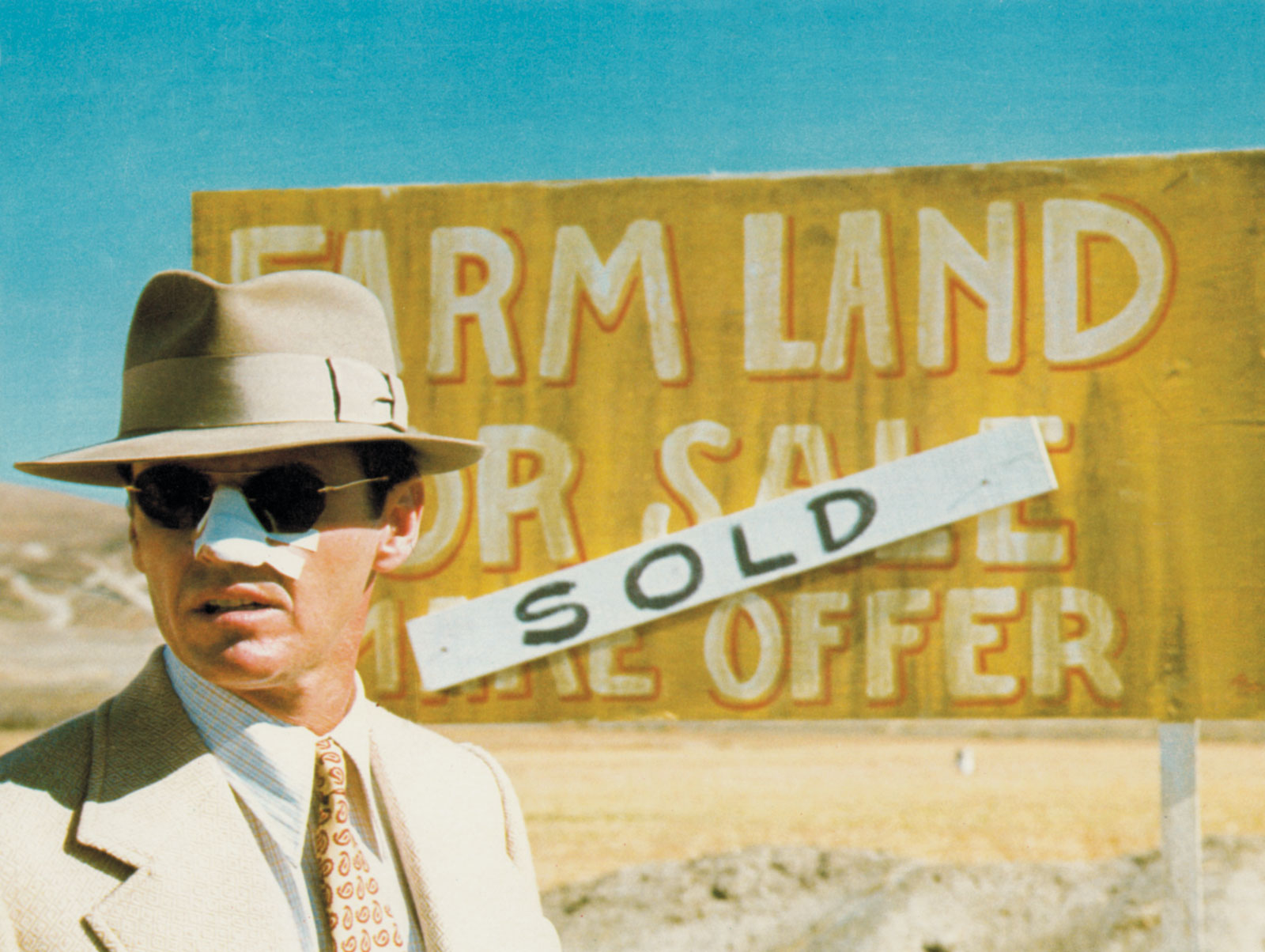

8. Chinatown (1974)

Jake Gittes (Jack Nicholson) is a hangdog private eye, hardboiled and shit out of luck. Blithely arrogant, his hunches almost always wrong, Jake exudes a vitriolic machismo, claiming here and there in the odd moment of clarity he experiences that he’s “just a snoop” in Roman Polanski’s neo-noir masterpiece, Chinatown.

Robert Towne’s script acts as a sort of compendium of film noir tropes and yet it defies them, it also wisely reflects glimmers of Greek tragedy, and, with Polanski’s near faultless direction results in a revisionist homage, that manages to be both cynical and sentiment in one fell swoop.

Masterfully evoking Hollywood’s Golden Age, even placing one of that era’s most dignified directors, John Huston (The Maltese Falcon [1941]) in a pivotal role, helps to underscore the assured audacity of the film that Roger Ebert said is “…a 1940s private-eye movie that doesn’t depend on nostalgia or camp for its effect, but works because of the enduring strength of the genre itself.”

7. The Conversation (1974)

Francis Ford Coppola dominated American cinema in the 1970s with the first two Godfather films and the war epic Apocalypse Now, but his provocative, cynical, and somber thriller The Conversation—itself a riff on Antonioni’s Blow-Up—is every bit as incensing and refractive as those larger scale pictures.

Gene Hackman is genius in his internalized and nuanced turn as surveillance expert Harry Caul. More at ease as an eavesdropper at a safe distance then actually interfering with people face to face, Harry is a hangdog antihero, lonely and secretive, he overhears and records a conversation with sinister overtones. The surveillance tapes seem to suggest something criminal, perhaps life threatening and Harry and the audience are soon swept up in a chimeric mystery.

As a postmodern study of paranoia and voyeurism, The Conversation is a first-rate film and one which reworked the Watergate scandal with striking similarities and feelings of dishonesty, spying, and governmental corruption. Harry’s obsessive investigation gets out of hand with tragic results that nonetheless hold the viewer spellbound and uneasy as the intrigue deepens.

In our modern milieu, The Conversation is a film that has aged incredibly well and seems more relevant and frighteningly realistic than ever before, and it’s last image is a haunting and heart-rending tableau of delusion and desolation.

6. The Night of the Hunter (1955)

Charles Laughton’s The Night of the Hunter is a whirling pictorial dervish, as well as a beautiful traumatic fable about a brother and a sister. Set in the Dust Bowl era, America is in the clinches of the Depression, but this here is no history lesson. No, this is a tale of two children, weakened and pursued by hysterical religiosity and the ignorance of the adult world.

Clearly a work of awe and evil, of enchantment and horror, The Night of the Hunter is one of those unshakable cinematic experiences that was misunderstood in its day but in the years since has been declared a masterwork.

An opiate-addled fairytale for grown-ups from the perspective of off-course and unloved children, Laughton together with legendary cinematographer Stanley Cortez (The Magnificent Ambersons, Shock Corridor), strove for and achieved a merger of German Expressionism and Film Noir composite. The results? It’s a work that is overflowing with high-contrast, jagged angles, strange shadows, distorted perspectives, and startling, surrealistic sets. The resulting distortion of reality works flawlessly to exaggerate the emotional onscreen experience.

The plot is simple; “Reverend” Harry Powell (Robert Mitchum) is a religious fanatic who becomes a full blown serial killer who targets the widow (Shelley Winters) of a petty thief he did some time with. Soon Willa’s two children, John (Billy Chapin) and Pearl (Sally Jane Bruce) must escape Harry before it’s too late.

Thick with nocturnal panic, The Night of the Hunter preys on things like our childlike fears of the dark, and the adult assertion of cruelty and persecution. Here a stolen doll becomes an emblem for innocence made absent, a riverside trek is bird-dogged by a deistic bully that further clouds the child’s-eye-view of a mature terrene that has lost its baby teeth. Once seen, you will never forget The Night of the Hunter, and that’s a promise.

5. Sorcerer (1977)

Based on the 1950 French novel “La Salaire de la peur” by Georges Arnaud, also the basis for Henri-Georges Clouzot’s towering 1953 film, The Wages of Fear (located further on down this very list), Friedkin’s take is that rare jewel that arguably transcends its origins to become something more intelligible, succinct, and exquisite then all its architects could have ever conceived. Sorcerer really is a kind of black mercurial magic.

In the dishabille, desolate swelter of Porvenir, Chile, four despairing men, strangers to each other and themselves, seek sanctuary and anonymity for disparate and dark reasons of their own. When a U.S.-owned oil company, vile in its exploitation of the people and resources in this out-of-the-way locale, through unsafe and incredulous practices, has an oil well explode, with heavy casualties, our anti-heroes begin to align in this unforgettable existential thriller.

Starring a badass Roy Scheider, and a brow-beaten Bruno Cremer, Sorcerer is, on the surface, a straight-up story of tough guys driving truckloads of highly explosive nitroglycerin across hundreds of miles of rocky terrain, impossible roads, collapsing bridges, and dense jungle furnace; their goal being the site of the oil well fire, their payloads to be used, should they survive the trip, to make an even bigger explosion to quench the furious fires that have already extinguished many ill-starred luckless lives.

“I measure the success or failure of a film on one thing—how close I came to my vision of it.” With this reclaimed masterpiece Friedkin’s resolute vision never lets up till the end, with a soft-touch finish that subtly takes everything apart. It’s a film that casts a shadowy spell, the obligatory happy ending eschewed for something far more spurring, but also, strangely, far more edifying. Sorcerer is a film whose dividends are dark and deep, like the craters of the moon that our lowlife protagonists seem to navigate on their quest through the eclipse.

4. Blow Out (1981)

Brian De Palma’s 1981 thriller Blow Out is his pièce de résistance, largely ignored on its initial release, though critically lauded, it’s the work of a master craftsman at the peak of his considerable powers.

Inspired in equal parts by Michelangelo Antonioni’s arthouse hit from 1966, Blow Up, and Francis Ford Coppola’s anxiety-addled 1974 thriller The Conversation (also on this list), De Palma’s mystery involves a movie soundman, superbly played by John Travolta, that may or may not have recorded a murder while on assignment capturing audio for an exploitation slasher film.

Without giving anything away, the plot widens as disparate characters surface –– Nancy Allen astounds as a call girl in peril, and a savage serial killer springs from the shadows, as does evidence of a conspiracy. The risks and rewards escalate, and all the while ambiguity and uncertainty reigns.

Pauline Kael wrote: “Seeing Blow Out is like experiencing the body of De Palma’s work and seeing it in a new way. Genre techniques are circuitry; in going beyond genre, De Palma is taking some terrifying first steps. He is investing his work with a different kind of meaning. His relation to the terror in Carrie or Dressed to Kill could be gleeful because it was pop and he could ride it out; now he’s in it.”

One of the many pleasures De Palma offers here is that his daring and audacious style is present and on proud display. Split-screen ruses, wild tracking shots, crazy point-of-view progressions, startling use of split-focus diopters, intense and emotional slow motion sequences, gallows humor, red herrings, Hitchcockian flourish and reveals; it all amounts to a dizzying, swelling Tell-Tale Heart climax.

So severe and flat-out horrific is the finish that Quentin Tarantino famously told De Palma that it was easily “one of the most heartbreaking shots in the history of cinema.”

3. Wages of Fear (1953)

“[Wages of Fear] has some claim to be the greatest suspense thriller of all time,” enthused film historian and documentary filmmaker Basil Wright of Henri-Georges Clouzot’s legendary 1953 thriller.

The Gallic master of suspense, Clouzot (Les Diaboliques [1955]) has often been called “the French Hitchcock”, and with Wages of Fear, he won best film honors at both Berlin and Cannes.

The moody, torpid first part sets the scene: Opening on a sweltering Latin American backwater populated by outcast expats who’ve gathered together hoping to make a quick buck in the American-dominated petroleum industry, and whom are now desperately seeking a way out.

The edge-of-your-seat narrative heats up exponentially as four foreign down-and-outers—a Corsican (Yves Montand), a Frenchman (Charles Vanel), a German (Peter van Eyck), and an Italian (Folco Lulli)—each agree to the dangerous duty of driving two truckloads of volatile nitroglycerine over the most treacherous jungle roads imaginable to an out of control oil well fire raging some 350 miles away.

The ensuing roller-coaster of tension is an unrelenting nightmare, and justifiably one of the most famous in cinema; too few films since have ever matched The Wages of Fear for messing-with-the-audience and leavin’-’em’-on-the-hook suspense. Sure, it’s a pessimistic vision of human endeavor, and it certainly ranks amongst the darkest in French cinema––a good thing––as it viciously swipes at the nasty economic imperialism of Big Oil (and heavily censored versions were originally released in North America as a direct result).

As you’ve no doubt noticed reading this list, William Friedkin’s 1977 take on this story, Sorcerer, also ranks very high on this list. Both films are adaptations of the 1950 French novel from Georges Arnaud, “La Salaire de la peur”, and both will most assuredly blow you away. Essential cinema times two.

2. Double Indemnity (1943)

“Since Double Indemnity,” raved Alfred Hitchcock, “the two most important words in motion pictures are ‘Billy’ and ‘Wilder.’”

Not just one of the earliest A-budget studio noirs, Double Indemnity may actually be the quintessential film noir, depending on who you ask. Based off the novella by James M. Cain and directed with precision and craft by Billy Wilder, the film tells the tale of insurance agent Walter Neff (Fred MacMurray), who’s persuaded by Phyllis Dietrichson (Barbara Stanwyck) to kill her husband for his life insurance. What could possibly go wrong?

Cinematographer John F. Seitz (who also shot Wilder’s the Lost Weekend [1945] and Sunset Boulevard [1950], pulls out all the stops in this influential and unforgettable film which has so many classic movie moments it’s no wonder it’s achieved such high status amongst film scholars and cinéastea. The unusual title sequence to Double Indemnity for instance, shows the agonized silhouette of a man hobbling on crutches towards the camera while Miklós Rózsa’s understated minor chords portend some creeping disaster that helps frame all that is to inevitably follow.

Here and throughout the subtle sense of malaise and despair––elements that made a huge mark on the French critics back in 1946 (this was a few years before the founding of the famed Cahiers du Cinéma)––writhes uninterrupted as much by its hard-bitten and unsentimental performances as at the hand of its seamy, atmospheric, and audacious visual style.

“If I had one movie to explain to people what noir is,” says film historian Eddie Muller, “it’s Double Indemnity.” Don’t miss it.

1. Psycho (1960)

Perhaps the most influential thrillers ever made, Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho is also one of the most visually arresting and artistically satisfying of suspense films. The Bates house, for instance, which overlooks the hotel, was inspired by Edward Hopper’s Americana-obsessed paintings, and this adds to the subconscious terror of this nerve-shredding masterwork.

Marion Crane (Janet Leigh) is a morally questionable heroine on the run who makes an ill-advised and totally fluke stop at the Bates Motel as she’s trying to get clear with $40,000 in stolen cash. Soon she’s having a jaw session with the good-natured Norman Bates (Anthony Perkins) before renting a room and splashing around in the most famous shower sequence of all time.

And the shower scene alone, a deft 3 minutes, is comprised of some 77 different camera angles containing 50 cuts. It’s a harrowing, expertly lensed, and geniously designed tour de force sequence that, when combined with Bernard Hermann’s shrill violins and Leigh’s blood-curdling screams, make for one of cinemas most memorable sequences.

Other scenes unravel with a delirious pace and flavor of impending doom, such as Detective Arbogast”s (Martin Balsam) unfortunate run-in with Norma Bates at the top of the stairs or even Lila Crane’s (Vera Miles) lonely walk up the steps to the looming, menacing Bates abode each contain their own mythic, otherly quality. Hitchcock was an undisputed master and Psycho is generous in its frequent shock imagery and unnerving visual craft. Psycho is, make no mistake, an absolute work of art from a groundbreaking genius and unquestionably deserves top billing on this exciting list.

Author Bio: Shane Scott-Travis is a film critic, screenwriter, comic book author/illustrator and cineaste. Currently residing in Vancouver, Canada, Shane can often be found at the cinema, the dog park, or off in a corner someplace, paraphrasing Groucho Marx. Follow Shane on Twitter @ShaneScottravis.