14. The Night of the Shooting Stars (1982)

One of the most beloved films from the esteemed Paolo Taviani and Vittorio Taviani, The Night of the Shooting Stars is a magical-realist fable that was inspired heavily from the tales the Taviani brothers grew up listening to in the Tuscany village of San Miniato in the 1930s. According to these legends, “the Night of San Lorenzo” is the basis for the titular night of the shooting stars, the charmed/cursed night when dreams come true in Italian folklore.

Set in 1944, a group of Italians flee their town after hearing rumours that the Nazis plan to blow it all to Kingdom Come, this is the film that sent Pauline Kael into a tizzy, writing: “[The Night of the Shooting Stars] is so good it’s thrilling. […] the film encompasses a vision of the world. Comedy, tragedy, vaudeville, melodrama –– they’re all here, and inseparable. […] In its feeling and completeness, Shooting Stars may be close to the rank of Jean Renoir’s bafflingly beautiful Grand Illusion.”

And Kael of course, was not alone in her high appraisal. The New York Times raved that the film was “revealing unanticipated beauties everywhere, even amid the horrors of war,” summarizing that Shooting Stars was “the Tavianis’ masterpiece.”

A lyrical, poetic, and fantastic feat set amidst World War II, Shooting Stars is one of the decade’s best films, and as its inclusion here rightly asserts, it’s also one of the 1980s most vividly ravishing.

13. Amadeus (1984)

One of the finest films from director Miloš Forman (One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest [1975]), this 18th century-set period drama, reworked from Peter Shaffer’s hit Broadway play, took home an impressive eight Academy Awards, including Best Picture, Best Actor (F. Murray Abraham), Best Director (Forman), Costume Design (Theodor Pištěk), Art Direction (Karel Černý, Patrizia von Brandenstein), and Best Makeup.

In the eponymous role, Tom Hulce is often over-the-top as the supremely talented young Viennese composer, and as his fierce rival Antonio Salieri, Abraham is appropriately sour, and even steals his share of scenes. Consumed by jealousy and bent on Mozart’s downfall, Amadeus is a lucid, larger-than-life pop art experience.

This gorgeous and grandiose film is as opulent as it is epic and unmissable.

12. Once Upon a Time in America (1984)

Co-written and directed by Italian filmmaking legend Sergio Leone, Once Upon a Time in America is, as Roger Ebert so succinctly phrased it, “an epic poem of violence and greed.”

This languorous and elaborate multigenerational saga of Jewish gangsters unfolds via flashbacks but begins in New York City, 1968, as aging David “Noodles” Aaronson (Robert De Niro) returns to the locale of his crime career going back to the Roaring Twenties and the Dirty Thirties. And while his longtime partner in crime, the hot-headed Max (James Woods) maybe ancient history, Noodles’s unresolved past and the people who populated it will be revisited with aplomb and with Leone’s unerring eye for detail, striking composition, and powerful imagery.

DP Tonino Delli Colli strikingly lenses the film, with particular care given to the recreation of New York’s Lower East Side, with a brilliant score from Ennio Morricone that seems to effortlessly add to the technical beauty on screen. It’s dazzling in so many ways.

As atmospheric and elegiac as anything Leone’s ever done, Once Upon a Time in America was the longest film of Leone’s CV, and sadly, it would be his last (he passed away shortly after production wrapped on the film). But, be that as it were, the film makes for a fine valedictory film; it’s a haunting evocation of America that’s both startlingly symbolic, and artfully introspective.

11. Diva (1981)

B-movie excitement frisks with pop-culture and high art in the ultra-stylish amalgam from Jean-Jacques Beineix, in what would come to be recognized as the first film in the Cinéma du Look movement.

Adapted from the 1979 crime novel “Diva” by Delacorta (aka Daniel Odier), this film left a huge impression on adventurous film critics like Roger Ebert who enthusiastically wrote that “[Diva] is filled with so many small character touches, so many perfectly observed intimacies, so many visual inventions—from the sly to the grand—that the thriller plot is just a bonus. In a way, it doesn’t really matter what this movie is about; Pauline Kael has compared Beineix to Orson Welles and, as Welles so often did, he has made a movie that is a feast to look at, regardless of its subject. […] Here is a director taking audacious chances, doing wild and unpredictable things with his camera and actors, just to celebrate moviemaking.”

Set in a gloriously vibrant Paris, Frederic Andrei is Jules, a young mail carrier who has become somewhat obsessed with the lovely voice of American diva Cynthia Hawkins (Wilhelmenia Wiggins Fernandez, wonderful). Cynthia, for her own rather idiosyncratic reasons, doesn’t believe in being recorded and so Jules secretly records her singing and then, wouldn’t you know it, Jules’s recordings of Cynthia are mixed up with another tape that incriminates a high ranking police official who has ties to the mob.

Beineix pulls out all the stylistic stops, pastiching the noirs of the 1940s, and cribbing several formal pages from the Jean-Pierre Melville playbook while he’s at it. A jaw-droppingly gorgeous film, Diva is a true work of artifice, and one who’s praises you’re likely to sing should it be a new discovery for you. Don’t miss it!

10. Paris, Texas (1984)

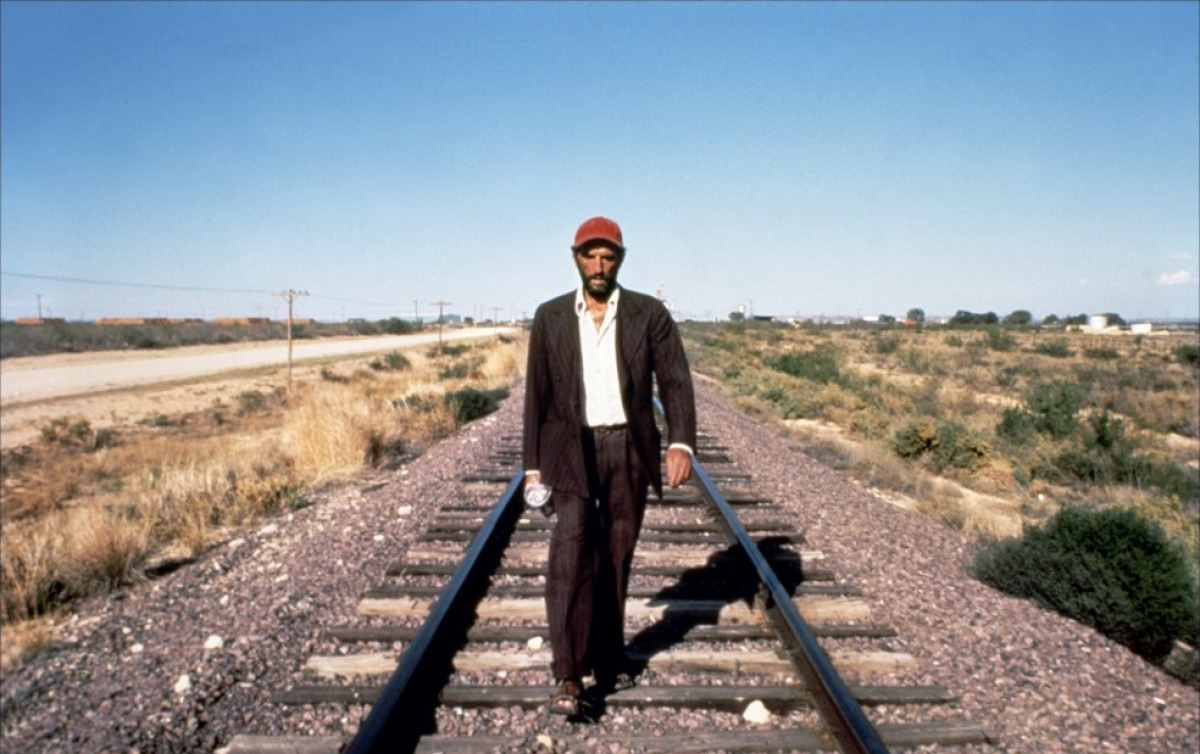

Making a tentative re-entry into civilization with hopes of reconciling with his young son (Hunter Carson) and estranged wife (Nastassja Kinski), Travis (Harry Dean Stanton, superb) emerges from the desert, a disparate and lonely figure, like a relegated Moses returning.

With a strong and farsighted screenplay from L.M. Kit Carson and Sam Shepard, shattering and sublime cinematography from Robby Müller, a memorable and moving score from Ry Cooder and the assured direction of Wim Wenders at the peak of his powers, Paris, Texas is something of a revelation.

The divide is too deep and the wounds too excruciating to ever wholly heal between Travis and Jane (Kinski) but redemption is still possible, even if their hearts will never be wholly healed. Few films are as elegiac, emotional, and honest as Wenders’ Paris, Texas. A gloriously visualized gem.

9. Fanny and Alexander (1982)

From first frame to last, Ingmar Bergman’s wonderful and wonder-filled evocation of childhood and the fascination of theater, Fanny and Alexander is a triumph by any measure, and may well be the Swedish icon’s crowning creation.

The winner of four Oscars (including Bergman’s third Academy Award for best foreign-language film), Fanny and Alexander begins during the Christmas of 1907, where ten-year-old Alexander (Bertil Guve) and his younger sister Fanny (Pernilla Allwin) enjoy the nostalgic warmth and gracious good humor of their eccentric extended family, the Ekdahl’s. Their lives soon take a saddening turn, however, with the death of their patriarch, their actor father Oscar (Allan Edwall) and the remarriage of their mother, Emilie (Ewa Fröling), to a puritanical Protestant minister, Edvard Vergérus (Jan Malmsjö).

Bergman’s very personal, semi-autobiographical tale is captured in glowing, rich images by his long-time collaborator, cinematographer Sven Nykvist. And truthfully, Fanny and Alexander offers up something not unlike a summation of Bergman’s work; with his chief themes on proud display, it may also be his most extravagant and most optimistic film — a pleasant and rather unexpected surprise, from an auteur forever synonymous with Scandinavian austerity and angst he bestows his audience with one last and lasting cinematic delicacy. Essential viewing.

8. The Sacrifice (1986)

“A stunningly beautiful film [that] rewards in burst after burst of beauty,” raved the New York Times in their original review of Andrei Tarkovsky’s devastating final film, The Sacrifice. Described in Tarkovsky’s own words as a meditation on what he called “the absence in our culture of room for spiritual experience,” it seems all the more fitting that this movie then, was filmed in Sweden with several of Ingmar Bergman’s valued crew (cinematographer Sven Nykvist chiefly amongst them).

Armageddon and the End of Days seems to be at the very crux of The Sacrifice, which is set on an isolated island, where Alexander (Erland Josephson, another Bergman regular btw), is a distinguished man of letters, lives in a bucolic idyll enjoying a peaceful (for now) semi-retirement. Soon Alexander’s prospects are abruptly upended by an unthinkable cataclysm, and acting in absolute desperation, he strikes an extraordinary bargain with God.

Winner of the Grand Prix as well as the FIPRESCI Prize at the 1986 Cannes Film Festival (Tarkovsky’s fourth!), it’s certainly one of the most stunning films of the decade. Filmed in the ethereal and almost unworldly northern light, and bookended with two of cinema’s most breathtaking and staggering single-take sequence shots, The Sacrifice is a transfixing and utterly unforgettable work of great formalism and intensity from one of cinema’s true visionaries.