7. Fitzcarraldo (1982)

“Fitzcarraldo is a movie in the great tradition of grandiose cinematic visions,” opined Roger Ebert, “like Coppola’s Apocalypse Now or Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, it is a quest film in which the hero’s quest is scarcely more mad than the filmmaker’s. Movies like this exist on a plane apart from ordinary films.”

The long gestating passion project from writer-director Werner Herzog –– the trials and tribulations of which have been expertly and elegantly documented in Les Blank’s unmissable behind-the-scenes exposé Burden of Dreams (1982) –– Fitzcarraldo is the arthouse adventure-drama that only a devoted auteur/raging lunatic could create.

And matching Herzog’s hubris, pound for pound, is Klaus Kinski as the film’s eponymous hero, the would-be rubber baron known in Peru as “Fitzcarraldo” but by his Irish parents as Brian Sweeney Fitzgerald. And it’s this ambitious madman who dreams of transporting a steamship over a steep AF hill in the remote jungle wilderness of the Amazon Basin, with the hopes of access to rich rubber territory being opened up, also allowing for a pipe dream about building an elegant opera house in Iquitos. Yeah, good luck with all that, hmm?

This magnificent testament to madness and the pursuit of happiness must rank amongst Herzog’s finest works. As Ebert succinctly writes: “[Fitzcarraldo] contains great poetic images of the sort Herzog is famous for: An old phonograph playing a Caruso record on the deck of a boat spinning out of control into a rapids; Fitzcarraldo frantically oaring a little rowboat down a jungle river to be in time to hear an opera; and of course the immensely impressive sight of that actual steamship, resting halfway up a hillside.”

Fitzcarraldo is a miracle, magnificently made for the rest of us to hang our most far-flung reveries upon.

6. Akira (1988)

The most influential anime of all time, Katsuhiro Ôtomo’s Akira is an ambitious and often breathtaking cyberpunk-addled post-apocalyptic pageant. Convoluted to a fault, Akira is set in Neo-Tokyo some years after a nuclear accident decimated the city, and it has been rebuilt, and yet still stands on the precipice of disaster thanks to government meddling with strange psychic superpowered kids. There’s also a wealth of youth biker gangs, oversexed kids and Juggalos mostly, out for kicks and dollops of ultraviolence plaguing the city.

Akira is best enjoyed if the frequently nonsensical narrative leaps of the bloated third act are largely ignored, and emphasis is put on the vastly detailed images and first-rate animation –– some of the best hand drawn imagery ever wed to celluloid. Akira is a feast for the senses, and for many it was the introduction to both manga and anime.

Blade Runner and cyberpunk fans will enjoy the many visual cues, the staggeringly detailed cityscapes and the absolutely awe-inspiring bike chases. Add a pulsating soundtrack from Tsutomu Ōhashi and you’ve got one of the most phenomenal films of its kind as well as the most technically dizzying and elaborate animated films of the decade.

5. A City of Sadness (1989)

“Our lives are full of fragmentary memories,” said Hou Hsiao-hsien of his films, in a recent interview. “We can’t give them names, we can’t classify them, and they have no great significance. But they lodge in the mind, somehow unshakeable.”

Regularly considered to be Hou’s unshakeable early masterpiece, A City of Sadness was the first Taiwanese picture to win the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival, and like Hou’s films that would follow after (A City of Sadness was only his second film), it’s a movie of languid grace, emphasizing extended takes and long, rigorous shots awash in burning colors.

Set soon after Japan relinquished its hold on Taiwan in 1945, A City in Sadness artfully depicts the tale of a family being torn apart during the “White Terror” of the Kuomintang (KMT) which resulted in thousands of Taiwanese being murdered or imprisoned (including the infamous February 28 Incident of 1947, where thousands were massacred).

“A master of long takes and complex framing,” wrote critic Jonathan Rosenbaum, “[Hou possesses] a great talent for passionate (though elliptical and distanced) storytelling.”

Chronicling the Lin family during tumultuous times, Wen-heung (Chen Sown-yung) is a bar owner and eldest brother, runs afoul the Shanghai mafia as middle brother Wen-leung (Jack Kao) suffers irreparable brain injuries courtesy of the KMT prison he’s wrongfully a captive of (ultimately leading him to an insane asylum), which leaves the youngest brother, Wen-ching (Tony Leung Chiu Wai). Wen-ching, a deaf-mute photographer, flees to the bucolic mountainside with his remaining friends, where they join the anti-KMT resistance.

Richard Brody of The New Yorker pointed out that “Hou’s extraordinarily controlled and well-constructed long takes blend revelation and opacity; his favorite trope is to shoot through doorways, as if straining to capture the action over impassable spans of time.” And similarly smitten by the film, Time Out’s Tony Rayns wrote that, “Loaded with detail and elliptically structured to let viewers make their own connections, […] Hou turns in a masterpiece of small gestures and massive resonance; once you surrender to its spell, the obscurities vanish.”

4. Koyaanisqatsi (1982)

“The film’s role is to provoke, to raise questions that only the audience can answer,” said Koyaanisqatsi’s producer Godfrey Reggio, adding; “This is the highest value of any work of art, not predetermined meaning, but meaning gleaned from the experience of the encounter.”

Expertly lensed by cinematographer Ron Fricke, and buttressed by Philip Glass’s staggering score, this highly experimental documentary from Godfrey Reggio accomplishes quite a lot from, narratively speaking, very little. Taking its title from the Hopi word that means “life out of balance”, Koyaanisqatsi uses ravishing imagery and music to detail to the audience the ways in which mankind has grown apart from nature. The results are avant-garde, eye-opening, and regularly jaw-dropping.

Comprised largely of astonishing and extensive footage of elemental forces, and natural landscapes, Koyaanisqatsi also depicts scenes of modern civilization and technology in ways that are frequently startling but also quite stunning.

Jarring juxtapositions combine eloquently with Glass’s often hypnotic score and the results often feel like a religious experience in what may be the finest non-narrative film ever made. A marvel.

3. Wings of Desire (1987)

Set in West Berlin two years ahead of the collapse of the wall, German New Cinema pioneer Wim Wenders offers up one of his most beguiling, beautiful, and ambitious films, Wings of Desire.

The mostly monochrome film, which is jaw-droppingly gorgeous to look at thanks to legendary cameraman Henri Alekan — Jean Cocteau’s celebrated cinematographer on La Belle et la Bête, coaxed from retirement by Wenders — follows two angels, Cassiel (Otto Sander) and Damiel (Bruno Ganz). The angels roam around Berlin, unseen and unheard by humans, and imbued with the ability to listen to the thoughts of anyone and everyone. It’s the ultimate act of voyeurism and it’s never less than completely compelling.

Damiel becomes smitten with a trapeze artist named Marion (Solveig Dommartin) and renounces his immortality in order to return to earth as a human. As a human Damiel loses the ability to eavesdrop on humanity and the film alternates from crisp black-and-white to fanciful Technicolor.

This astonishing and visually ravishing film, a high-point in Wenders’s considerable oeuvre, deservedly won Best Director at Cannes. This film is an absolute masterpiece, and if you’ve yet to see it for yourself, take our word for it; you’re in for a treat.

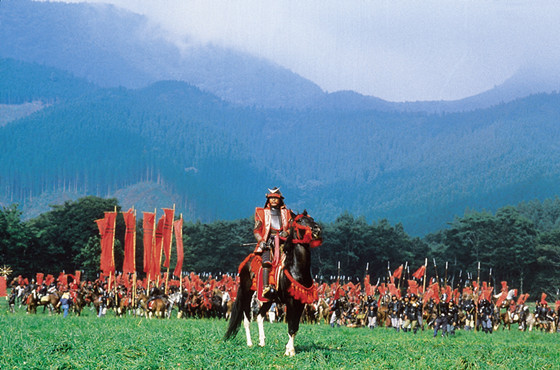

2. Ran (1985)

“The physical scale of Ran is overwhelming,” wrote Gene Siskel in his original Chicago Tribune review, adding: “It’s almost as if [Akira Kurosawa] is saying to all the cassette buyers of America, in a play on Clint Eastwood’s phrase, ‘Go ahead, ruin your night’ — wait to see my film on a small screen and cheat yourself out of what a movie can be.”

A long-gestating passion project from a legendary Japanese filmmaker, Akira Kurosawa directed, edited, and co-wrote (along with screenwriters Masato Ide and Hideo Oguni) this powerful period tragedy, derived from both Shakespeare’s King Lear as well as incorporating legends of the daimyō Mōri Motonari (a 16th century Japanese ruler). Hailed by Kurosawa as “a series of human events viewed from Heaven”, Ran has also been praised ever since its release for the power and scope of its poetic imagery as well as its incredible use of color.

Starring Tatsuya Nakadai as Great Lord Hidetora Ichimonji, a seventy year-old Sengoku-period warlord who decides to abdicate and divide his domain amongst his three sons; the eldest, Taro (Akira Terao), will rule; his second son, Jiro (Jinpachi Nezu), and his third, Saburo (Daisuke Ryu) will take command of the Second and Third Castles but are expected to unquestioningly obey and support Taro. Soon Saburo defies the pledge of obedience and is banished, and despair and destruction will soon follow.

There’s so much to appreciate and marvel over during Ran’s two hour and forty minute run time (and it breezes by effortlessly), least of all being the gobsmackingly grand period detail and production design from Shinobu and Yoshirō Muraki; the gorgeous costume design from Emi Wada (who deservedly won an Academy Award for Best Costume Design for her amazing efforts); and the thrilling trifecta of talented cinematographers (Asakazu Nakai, Takao Saito, and Masaharu Ueda).

Ran is one of the few supreme cinematic achievements, not just of the 1980s, but of the 20th century. Not to be missed.

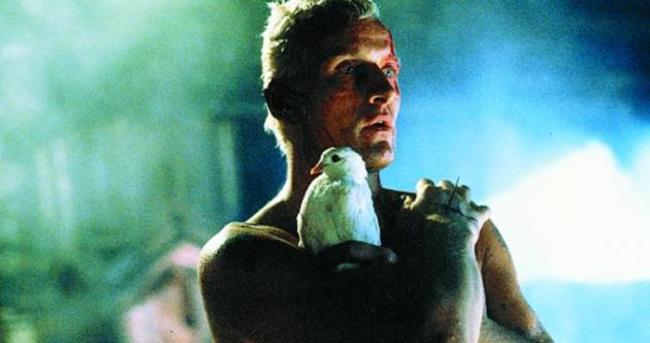

1. Blade Runner (1982)

Ridley Scott’s gritty gray postmodern adaptation of Philip K. Dick’s classic sci-fi novel “Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?” (1968) anticipated the advent of cyberpunk and reworks familiar film noir trappings to make one of the most iconic and inspired films of the 1980s.

Set in a smog-shrouded 2019 Los Angeles, Earth has an overpopulation problem, so off world colonies are all the rage. Sweetening the pot of relocating to foreign planets is the Tyrell Corporation who have designed “replicants” –– essentially designer humanoids –– to work as slave labor and with a limited lifespan. When these replicants go AWOL, a fate which befalls many, it’s the job of the “blade runner” to hunt them down.

Enter laconic former blade runner and disenfranchised ex-police investigator Rick Deckard (Harrison Ford), summoned back into action from the bureau to “decommission” four rogue replicants led by one Roy Batty (Rutger Hauer). Ostensibly the villain of the film, Batty morphs into a mythic tragedian, a modern Prometheus; Deckard, meanwhile, moves from two-fisted hunter to homomorphic malefactor.

Blade Runner is over full with opulent imagery as it busies itself with questions about what it means to be human, dissecting ideas of A.I., consciousness, reality, and other requisite sci-fi themes while paying perceptive adulation to wide-ranging influences such as Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1926), James Whale’s Bride of Frankenstein (1935), Stanley Kubrick’s 2001 (1968), the illustrative grandeur of French comic book legend Jean Giraud (aka Mœbius), the compositions of Edward Hopper, the aesthetics of film noir, and detective fiction à la Raymond Chandler, not to mention being overripe with religious allegory. Blade Runner is a densely packed table d’hôte.

Author Bio: Shane Scott-Travis is a film critic, screenwriter, comic book author/illustrator and cineaste. Currently residing in Vancouver, Canada, Shane can often be found at the cinema, the dog park, or off in a corner someplace, paraphrasing Groucho Marx. Follow Shane on Twitter @ShaneScottravis.