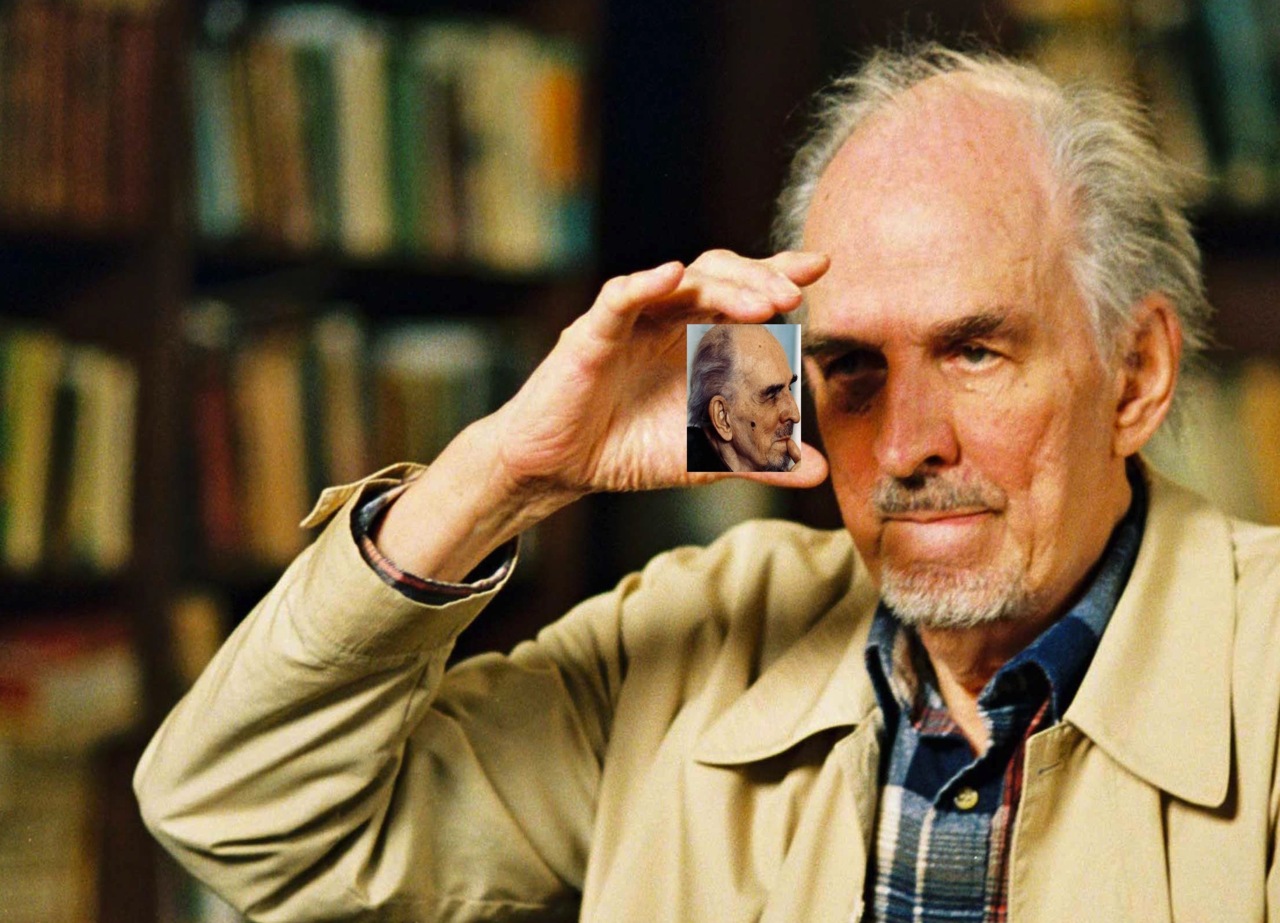

11. Ingmar Bergman

During the suffocating moral tyranny of the restrictive Hays Code in the United States, a more pensive, libertine cinema was emerging in Europe. At the forefront of this movement was Swedish director Ingmar Bergman.

Bergman’s films are impossible to categorize in their entirety, apart from their university. Be it set in Medieval Europe or working-class Stockholm, Bergman’s characters are eternally sympathetic and relatable; no matter the depth of the subject matter.

Bergman typically dealt in grandiose, abstract concepts, such as youth and poverty, aging, the absence of god, or retribution. In a time where provocation of any time was widely stifled in cinema, Bergman’s 1953 Summer with Monika, Bergman treated the film world to one of the more gratuitous nude scenes in early modern film.

Part of Bergman’s lasting influence is undoubtedly his ability to make thoughtful, philosophical, understated features without sacrificing entertainment value.

12. Agnès Varda

Though women had been a key component in the filmmaking industry since its genesis; typically occupying more humble yet crucial roles such as editor, screenwriter and cinematographer, or existing as thankless, socially-conscious directors like Lois Weber; the presence of women and film rose to great prominence with the emergence of feminist Left Bank filmmakers like Agnès Varda.

Considered a pioneer in the French New Wave aesthetic for her guerilla filmmaking tactics such as unprofessional actors and modest set pieces, Varda was noted through films such as Cléo de 5 à 7 for her capacity to present a uniquely female brand of cinematography, wherein her protagonists were impervious to objectification and possessed a fortified personal identity and motivations.

Varda’s films served as a great source of inspiration to other feminist filmmakers; with Cléo de 5 à 7’s influence particularly present in Chantal Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles. Upon receiving her Academy Honorary Award in 2017, Varda’s contributions to women’s cinema were lauded by Angelina Jolie and Jessica Chastain.

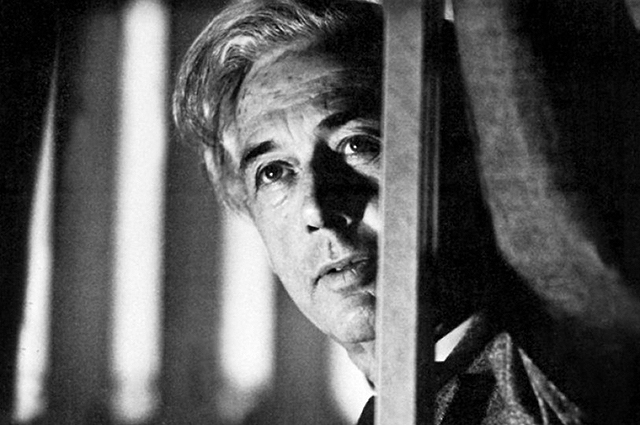

13. Robert Bresson

Of all the influential filmmakers covered on this list, Robert Bresson has probably gotten the closest to manufacturing a “pure” brand of cinema. One can see in Bresson’s choice of mise-en-scène that he is obsessed with trimming all impurities from the action he is trying to depict. For example, in A Man Escaped, as well as Pickpocket, if the protagonists are working with their hands, only the hands would be shown; everything else is secondary. This is punctuated by his restrained use of music in film, and his the natural performances by unprofessional actors.

A deeply spiritual, humanist filmmaker; Bresson’s minimalistic, to-the-point style was a significant departure from the extravagant, decorative French films of the era which were further rebelled against by renegade cineastes like Jean-Luc Godard…

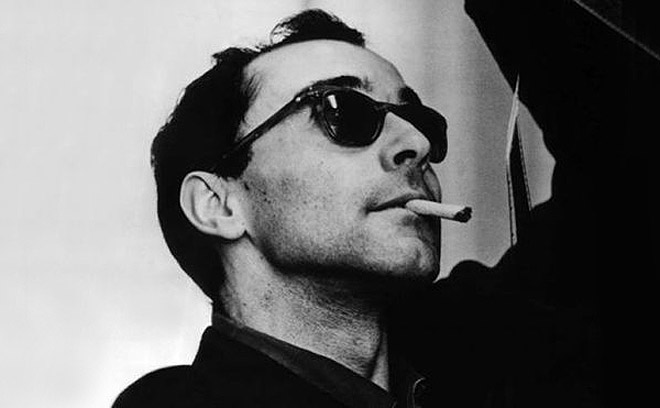

14. Jean-Luc Godard

What would happen if a filmmaker were to glean only the noblest lessons from the filmmakers in this list, pervert them beyond recognition, then throw the rest out the window? The answer to this lies in the cinema of Jean-Luc Godard. Building on the proletariat filmmaking style expounded by his peers at Cahier du cinema magazine such as François Truffaut and André Bazin, Godard’s films trifle with conventions of plot, montage and film logic whilst still tipping their beret to the true auteurs such as Hitchcock, Nicholas Ray, and Howard Hawks.

Some of Godard’s signature filmmaking traits include erratic jump cuts and unorthodox mise-en-scène; the use of handheld cameras; along with unconventional plot structure lacking closure and resolution; and leftist political undertones. The pessimistic realism of his plots that spit in the face of audience expectations and his disruptive, sacrilegious rule-breaking editing techniques would be of great influence to American filmmakers of the late 1960s and 1970s.

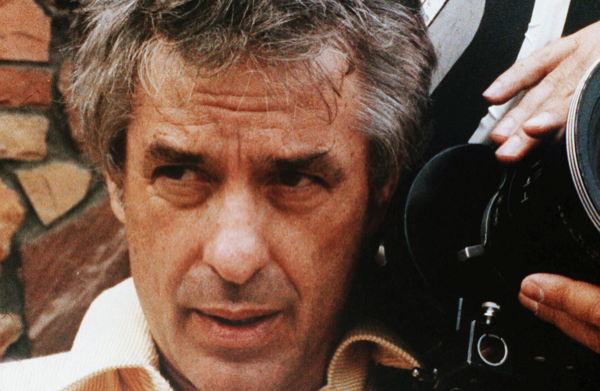

15. Rainer Werner Fassbinder

A new type of filmmaker for a new type of society, Rainer Werner Fassbinder tackled modern issues head on, but in an extravagant, ageless style reminiscent of Douglas Sirk’s melodramas.

In the wake of civil rights movements, second-wave feminism, globalization and the Vietnam War; it was clear that what in past generations would have been considered provocative features no longer carried any bite or relevancy; the world had grown up. In his films, Fassbinder evokes the signs of the times through his exploration of issues such as immigrant labour, interracial romance, and homosexuality.

However, Fassbinder was also a provocative filmmaker in that he was notorious for being regularly off the mark. Too left-wing for conservative critics, yet condemned by the Marxists; labelled sexist by feminists for the politics of his all-female cast film The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant, yet considered obscene by bigots for his frank portrayal of homosexuality in the German working class in Fox and His Friends.

Perhaps most interestingly about Fassbinder’s—himself bisexual—treatment of homosexuality in film is his hesitance to use the social implications of a gay lifestyle as a plot device as so many filmmakers of the era would; instead opting to portray same-sex relations as a non-issue.

In 1982, Fassbinder died with the intensity with which he lived, succumbing to an overdose of cocaine and barbiturates at the age of 37. His work would be a cornerstone in the postmodern New German Cinema movement alongside Wim Wenders and Werner Herzog. His penchant for making provocative, socially conscious films—even at the risk of his own condemnation—would go on to inspire disenfranchised artists everywhere.

16. Andrei Tarkovsky

Soviet auteur Andrei Tarkovsky once famously remarked that he “was only interested in the views of two people; one is called Bresson and one called Bergman”. Incidentally, Tarkovsky would go on to earn the same level of credibility amongst future generations of filmmakers.

Tarkovsky’s atmospheric filmmaking style combines the purism and subtlety of Bresson with the hefty philosophical notions of Bergman, with just a dash of Kubrickian subject matter. In an era where science fiction was either regarded as derivative of 2001: A Space Odyssey, or mindless entertainment, Tarkovsky’s Solaris stood alone.

After the release of Star Wars in 1977, Tarkovsky’s pensive, atmospheric brand of science fiction remained unharmed by the new wave of Hollywood space-fare and he made the haunting philosophical sci-fi standard, Stalker.

Be it an ethereal science fiction drama or his more earthbound films, Tarkovsky’s style may evoke the greats of cinematic purism, but he is careful not to fall into a trap of homage à la Tarantino. The most important thing Tarkovsky lifts from the greats is to go his own way, to create and innovate and not to strive to be the next Bergman, but the first Tarkovsky.

17. John Cassavetes

Contrasted with the hardened, irresponsible coolness of the French New Wave and the unattainable splendour of European art cinema, a more DIY approach to filmmaking was emerging in America thanks to John Cassavetes.

Amateur features made with a group of close-knit collaborators on shoestring budgets about real people with relatable problems made Cassavetes one of the founding fathers of the American independent film. Unlike the films of the French New Wave or of artists like Federico Fellini that purported to be less sugar coated than the films of yesteryear, they still carried a certain dishonest glamour that Cassavetes circumnavigates by telling all too real stories of failing marriages, midlife crises and dysfunctional families.

Cassavetes’ aesthetic of getting a movie done by whatever means necessary—finances and equipment be damned—and putting heart first would be of immense inspiration to generations of indie filmmakers.

18. Stanley Kubrick

One can accurately describe Stanley Kubrick as a “big idea” filmmaker. Though he would have quickly mastered the genre of modest kitchen sink dramas if he put his mind to it, his films are predominantly concerned with bold concepts such as the progress of humanity, dystopia, insanity, war, and excess.

Despite these big ideas, Kubrick is also a deeply satirical filmmaker, who seems to enjoy the vision of humanity making a fool of itself in the face of such daring subject matter as war, politics and totalitarianism.

As an innovator, Kubrick was notoriously preoccupied with pushing technical boundaries and finding new ways to make better films, such as his desire to shoot only with natural light on the period piece, Barry Lyndon.

One key feature of Kubrick’s oeuvre is the meticulous attention to detail and the alleged symbolism that goes into each of his shots. He receives attention from film scholars and amateur enthusiasts alike for the supposed depths of subliminal metaphor in every frame. Examples of this include the Native American logo in the background shot of The Shining evoking parallels with the indigenous genocide; or in 2001: A Space Odyssey, with the interpretation of the alien monolith as a cinema screen.

19. Martin Scorsese

The evolution of American cinema in the 1960s was marked by several trends. Firstly, there was the visible shift from the apprenticeship-driven studio method of learning the craft, to the prevalence of film schools. Other trends include the deterioration of the already impotent Hays Code and a departure from the WASPy West Coast “Old Hollywood” studio production model, and the rise of a more unpolished, street-level East Coast cinema; one of the founding fathers of which is Martin Scorsese.

Raised on a steady diet of golden age American cinema, as well as an international selection such as French New Wave, Brazilian and Asian cinema, alongside Italian Neo-Realism; Scorsese figured out how to take the post-war ruins of Rossellini’s Rome and sub them out for the seedy ruins of his own New York City. His themes of machismo, desperation, excess, conflict and hypocrisy in the Roman Catholic/Italian-American community, and the world of organized crime would impact the gritty tone that would permeate through the 1970s; the disillusioned age of the anti-hero.

20. Steven Spielberg

Although in more haughty critical circles, Spielberg’s name is scoffed at for being too “mainstream” or too “Hollywood”; and rightfully so. Steven Spielberg is nothing if not Hollywood.

Spielberg’s strength as a filmmaker is derived from his recognition of the power of spectacle, and the relatable elements that have the power to ground even the most out-of-this-world plots and scenarios. The entire concept of the summer blockbuster is attributed to Spielberg’s Jaws (and to a lesser extent the emergence of air conditioners in multiplexes).

Naturally big budget entertainment existed prior to Steven Spielberg, but prior to his emergence; few other filmmakers had devoted such finance and care to genre films since the days of the epic features of the 1950s.

Indie filmmaker Kevin Smith once remarked that without Spielberg, Jews would have been a Roger Corman style B-Movie, and that it took a mind like Spielberg’s to treat such a tale so seriously and write it so large.

Spielberg may flourish most as an entertainer, but he’s proven himself capable of dealing in more mature subject matter with features such as The Color Purple, Munich, and Schindler’s List.

His influence can be regarded as both a blessing and a curse. The term “Oscar bait” has been thrown around with a great degree of condescension in recent years, but the popular recognition of Steven Spielberg’s contributions to genre cinema and other populist filmmakers cannot be ignored.