17. Happy Together (1997, Wong Kar-wai)

What was supposed to be a trip of finding revelation in Argentina turned into a study of loneliness, in a vicious cycle of despair, forgiveness, nice moments, quarrels and repeated despair. Ironic, given the title. One partner gives a bad impression from the start: rough, violent, prone to infidelity… but the actions of the other are more destructive: possessiveness, jealousy, a desire for control(the theft of a passport and all the desperate attempts to make the first one stay from leaving again).

We come to the question: is there an hour, now, in the past or in the future, where this couple could be happy together? The answer that can give hope can be found in an isolated scene of dancing, one of the most beautiful moments seen at the festival, but that is a rarity.

Wong Kar-wai and scenographer Christopher Doyle made an effort to showcase the turbulence of a relationship visually as well: moments from the past are abound with grayness, while the period in the new cycle is colorful and warm, luring us into thinking that some better situations are coming.

Delving deeper into the prevalence of colors, we see that the ones that fill the most space are brown and yellow, nuances that guide to a state of sadness and turmoil, the sepia-like tone alluding further to existentialism or unwanted future. The master of melancholy delivers again a work worthy of attention, so much so that the more troubled viewers won’t even notice that the story includes two men.

16. Punch-Drunk Love (2002, Paul Thomas Anderson)

Born after Anderson’s decision to make a 90-minute movie in collaboration with Adam Sandler, this small personal project is an unconventional love story. What first catches the eye is the skill with which Anderson brought out the maximum from Sandler.

Combining the properties of all the characters Sandler played in his comedies, for whom he will become hated over the years, he’s created one realistic depiction. Barry is an unpleasant, emotionally anguished, anxious person, hardly establishing contact with other people, thus making him connect with many people in the audience that felt this way at least once in their lives.

Sandler is a revelation in this role, making it a little disappointing that his career didn’t go in that direction. The look of the film nicely supplements the character, with its vibrant colors and distorted cadres.

With Emily Watson as Lena, equally flawed and cuddling as Sandler’s Barry, and Anderson’s standard collaborator Philip Seymour Hoffman, “Punch-Drunk Love” is at the same time the director’s funniest and his most touching work. With the angriest and most hilarious phone call you’ll ever see, let’s not forget.

15. The Player (1992, Robert Altman)

Never someone to step down from critique of the many classes of people, this time Altman is turning to the institution that made him – Hollywood itself. What we get is satire so great that even after multiple viewings it’s hard to catch all the details. Building a movie on washed up Hollywood clichés, he is at the same time viciously attacking and criticizing them. Brilliant!

Many things are worth the prize in this star-filled, meta masterpiece. That can be seen right at the beginning, with a long shot around the studio where, by giving honors to past masters like Welles, Altman himself becomes one of them.

A film where fiction and reality melt, every moment is an elegant yet direct finger pointing at the machinery that makes easily digestible but poor quality content; the producers and writers greenlighting it; and the public itself, who unquestionably allows for heroes to go unpunished for their sociopathic tendencies, instead getting rewarded for them (the end).

Always mild and subtle, but a discreet critique. We should also mention Tim Robbins, who, while not being an evil man, is full of cynicism and impudence, pulling it off without any anguish. Almost like he’s used to seeing it…

14. Cache (2005, Michael Haneke)

Leave it to Haneke to terrorize an upper middle class family, frighten you, and along the way ask a few important sociocultural questions. The first shot, a static video from the corner of Rue des Iris street, will become one of the traumatic film recollections that stays engraved in thoughts.

At first monotone and impersonal, this cadre slowly turns into a source of paranoia, terror and uncertainty. A voyeur is among us and, even if we are all voyeurs in this context, this one has sinister intentions, which is something an aggregate of three main protagonists finds out the hard way.

Over nearly two hours, the characters (and the viewers) are being unnerved by a torturous provocateur (or someone much more dangerous) getting their lives out of balance. The time goes by, questions are piling up, but the answers are very few. With the last clapboard it is hard to come to the conclusion by yourself.

With this, Haneke wanted to address the notion of collective guilt, information that’s hard to catch in the first viewing, but the signs are there. The always turned-up TV on the side alludes to that with the, then actual, news about the conflict in Palestine, but also with the quick mention of an event from the early 60s that gives new dimensions to particular characters. Brutal and uncompromising, give it a shot as soon as you can.

13. La Haine (1995, Mathieu Kassovitz)

In a film covering 24 hours, Mathieu Kassovitz, a one hit wonder, delivers one of the best realized tales about hate, racism and poverty. In the story’s focus are Vins, Hubert and Said – a Jew, an African, and a Muslim, respectively; all are representations of the biggest minorities in the city of light.

Vins (a newer, younger, and never brighter Vincent Cassel) is a force of nature. He starts as a naive, cocky youngling (playing bad boy in front of a mirror while quoting “Taxi Driver”) and in a few fantastic minutes with the addition of bad information, he transforms into a character to stay away from.

A terrifying personification of hate. Hubert is the rational one of the group, the most mature one, the one who is calming the fire and wanting to escape the violent past. Said is in the middle, a sacrificing maverick, attaching traits from both ends of the spectrum his friends are representing.

Together these three youthful guys are presented with the hellish everyday situations of a Parisian ghetto where racism, police brutality and wrongful captures are frequent. All this anger, with a big dose of disbelief and a beautiful, if rigid, black and white camera, is captured by Kassovitz, who never repeated this level of mastery later on.

This is a bleak reality, reflecting today’s France, but alluding on the brutality all over the world, especially a little more southeast in Europe. A French film directly from the Balkans and one of the most deserving awards for best directing at the festival.

12. Drive (2011, Nicolas Winding Refn)

It took only five minutes for Nicolas Winding Refn to pull us into a world of neon lights, retro 80’s inspired electro music, and over-the-top violence. And in those five minutes, Gosling’s almost mute driver shows his first characteristics: he doesn’t carry a gun, he is not getting his hands dirty – he drives. And he does it outstandingly.

Calculated. Don’t let this fool you, under the surface lies a fleshed out character, because he is a real human being even if the terrifying, empty stare, monotone speech and liters of blood he leaves behind say otherwise.

Refn’s American debut is a combination of style and substance, art house and mainstream. Masses will be drawn in by the smoothly flowing chase scenes and unbelievable killings, but some will find highlights in the great character study. All the slaughter and debauchery aside, the heart of the film is the warm and sweet relationship that Gosling has with Carey Mulligan.

With this role, the luscious actor finally showed that he is a force of A+ category, something he was trying to prove since the debacle that was “The Notebook.” So sit comfortably in your seat, put on Kavinsky to the max, and prepare for the drive of the decade.

11. Fitzcarraldo (1982, Werner Herzog)

To talk about this film means an eventual coming to the situations behind the camera. Legendary production problems that threaten to overshadow the film itself include the murderous love-hate relationship between Herzog and Kinski (that came to such candescence that some crew members offered to liquidate the latter), all the troubles of shooting on location around the Amazon, the carrying of a few-hundred-ton-heavy steamboats up the Andes, and the possible exploitation of the indigenous people; and these are only the most vocal accidents from the set. But even with all the drama, the final product is a gem worth talking about. Kinski, never more sane, but with a noticeable dash of madness (“I want my opera!”), is an atypical protagonist for this story.

Stories set in the jungle allude regularly to craziness. This is not “Apocalypse Now,” nor is it the duo’s primary collaboration, “Aguirre.” Fitzcarraldo is not a mindless conqueror, but a determined and passionate opera lover, almost sympathetic in his quest to get rich so he could build an opera house in the heart of a jungle, while his rivals and companions are mocking him.

It could be said that the conquistador here is Herzog himself, mercilessly getting his vision into reality, not caring for consequences. The scene of the ship lifting up the mountain, which comes almost two hours into the film, is a visual and technical miracle, and Herzog captures every moment with an almost documentary-like precision.

In the end, both the director and his personified character in the form of Kinski triumph, getting respect and glamour along the way. A film for those who dream.

10. A Man Escaped (1956, Robert Bresson)

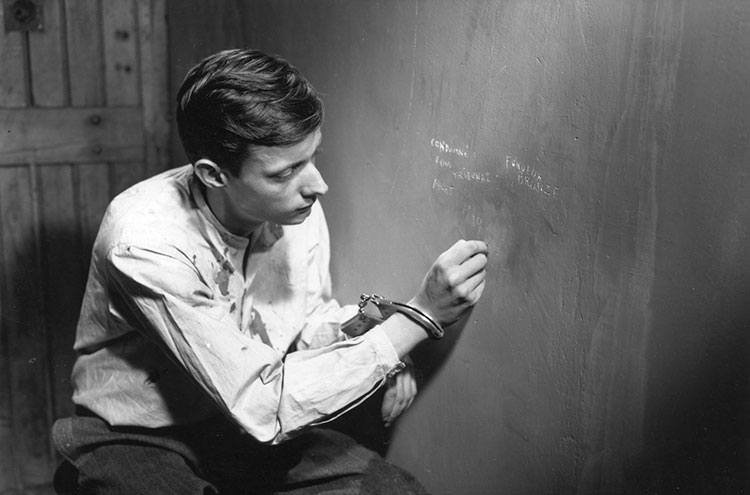

Getting into the fine details. It is the essence Bresson wanted to convey with this minimalist work, one which many consider to be the best accomplishment of the French maestro. To explain the movie plainly is simple.

A member of the French resistance movement is captured, convicted and imprisoned in a Nazi prison, devising a detailed plan to escape. Yes, the ending was just spoiled for you. The title itself, however, was no less successful in hiding the last few minutes.

Bresson was not interested in the goal, only in the funds. Patient and passionate, the director shows each of Stephen’s steps: his violent “interrogation,” the first steps in establishing contact with other detainees (made in ghostly silence), the process of obtaining material and its subsequent transformation into the escape tool, etc.

Due to the constant exposure to the actions and the thoughts of the protagonist, the viewer begins to identify: the paranoia is there with every passing minute, the four faceless walls adding to the already present claustrophobia.

When unexpected events happen, Fontan is not the only one who doubts; conflicting thoughts also affect you. Bresson may have made a simple free-action movie, but those minute moments, to which minutes and minutes have been dedicated, make the whole experience more powerful.

9. Naked (1993, Mike Leigh)

Some movies use striking imagery to convey and leave a memorable or horrifying picture implanted in the memory. This one is different – it uses words. Here, Leigh completely ditches positive morals and the middle class and digs deep into the far end of the societal ladder.

At that bottom is, completely in black, an intellectual drifter named Johnny, played to perfection by David Thewlis. This is a one-man show, because Johnny is a such a giant of a character. A misogynist, anarchist and nihilist – Johnny is a monster. An eerie being that with his mere appearance can send chills down your spine.

Then again, we are drawn to him, admitting with a heavy heart that sometimes we see ourselves in this monster, as much as we want to hide it. The reason being the outstanding writing by Leigh, who makes Johnny a real multilayered and fascinating character, giving him some of the best monologues and dialogues recorded on film.

Because Johnny, even with all his flaws, is highly intelligent and educated. In the two hours of the film’s run time, themes such as existentialism, religion, relationships and sex will be shown in a totally different light.

The 10-minute dialogue that Johnny has with a mall guard is one of the most inspiring, but also the one that instills awe. The film does not hold back any punches, all ideals and characters (including the small but strong supporting crew) will be reduced to nakedness. Be afraid…