8. Time of the Gypsies (1988, Emir Kusturica)

It was a collaboration of two artists at the height of their creative carriers. “Time of the Gypsies” (Dom Za Vešanje) presents the turning point in Kusturica’s work. A mixture of realism and fantasy, this film was a farewell to the former, and an open door to the latter, one in which Kusturica will find his greatest success.

Located in a cardboard settlement of Belgrade, the film is a look at the world of the Romani, represented by the boy Perhan. The director has always had a soft spot for the minorities of South and Eastern Europe and with this feature he is sending them a love letter (and a warning).

With actors of Romani descent and with an authentic dialect, Kusturica lets the neglected culture to breathe freely. He shows both its good and its bad sides. The positive ones we are going to focus on first, because in those scenes Kusturica shows his maximum and probably the most beautiful directing seen in his works.

The Djurdjevdan celebration scene on the river takes on the likeness of a lucid dream. With “Ederlezi”(a masterpiece from the other “artist” responsible for this gem, Goran Bregović) thrown in, that scene turns into minutes of immeasurable beauty of picture and sound.

The bad side is that what was tormenting the community for decades – poverty, crime, human trafficking – are personified through the character of Ahmed (played to perfection by the legendary Yugoslav/Serbian actor Bora Todorović, who spent months living and befriending the Gypsies so he could better depict the role).

The last minutes become standard Kusturica practice: a macabre of madness, this time with a heartbreaking ending. “Time of the Gypsies” is everything: a fantasy of laughter and sadness, filled with dark yet heartwarming moments. Funny but also tragic. A dream you don’t want to end.

7. Wings of Desire (1987, Wim Wenders)

It takes a gifted director to draw out human emotion in celestial beings, but here is Wenders, pulling it off with ease, without showing a shred of effort. This is visual poetry and a love letter to the then still-divided Berlin, wishing it the best, not knowing that the same will happen only two years later. The first act is a gorgeous introduction to the troubled world, where the thoughts of millions levitate in the air.

For almost half hour, the viewer stops being just a viewer, but is turned into a watcher among the angels, giving glimpses of hope to the concerned adults during hard times and smiles to the faces of children, whom this worldly worries don’t affect. When the themes shift to love, the film becomes a celebration of humanity.

Angels, as exalted as they are, don’t have what we as flawed beings value so much – feelings. Marion’s act on the trapeze is enough to convince one angel to try living among mortals (truly, there doesn’t exist a person that in that moment didn’t fall in love with Solveig Dommartin, as melancholic as that scene was). Elegiac but also deeply touching, “Wings of Desire” is a beautiful love story, spiced to be much better due to the appearance of Nick Cave and his unique numbers.

6. The Diving Bell and the Butterfly (2007, Julian Schnabel)

There are a few reasons why this drama should be among the greats. The first and simplest one is that it addresses Locked-In Syndrome, a rare but profound disability. The second is that it’s a story about the given syndrome, presented in a raw, non-manipulatively emotional but still magical way, honoring not only the author but all the people who are affected by it. The third is the method in which the director puts us in the story.

From the start, we are thrown into a first person perspective. Like Jean, we are also confused and limited. Perception as we know it is gone. We are trying to understand that life will never be what it was and that we need to find other ways to make ends meet. The first hour really omits pessimistic vibrations; enclosed, we feel that we are captured in a diving sarcophagus that is slowly sinking to the bottom. However, imagination and wit are still intact.

With enormous persistence and generous help from professionals (the scenes with re-learning communication are presented with documentary-like precision), the cage is breaking; we are free as a butterfly and the perspective changes from first person to third person.

The world is again within arm’s reach, even if desires for some feelings (like tasting food again or sexual touch) remain. You are handling reality. Another celebration of life that at the same time acknowledges and honors death. Probably the most inspiring film you can find.

5. Mulholland Drive (2001, David Lynch)

“Mulholland Drive” is nightmarish right from the first few minutes, in which a very surreal dance competition is shown and continues to be that way all through its flow. The feeling of uneasiness only intensifies with the arrival of a particular scene in a restaurant early on in the film.

After that, you continue to watch with nervous sweat on your forehead while your palms are scratching the armrests. You wish for the uncertainties to stop, but the sadistic urges from the depths of subconsciousness are cheering you on to enjoy the unreal cadres of Lynch’s peak.

It seems the director was always fascinated with Hollywood glamour and its stars, but always criticizing the machinery you need to cross so you can get to that. Reality and dreams merge ideally, while the tormented viewer tries to compile the pieces of this intricate murder mystery masked as a noir, masquerading as a breaking of the illusion of sweet reality about success.

Once again Lynch tickled our libido with sensual and forbidden sexuality, once again he left us distraught at the end, once again he made us feel disturbed when we hear the lovely lyrics of Roy Orbison songs, and once again he proved that he is one of the most intriguing contemporary directors.

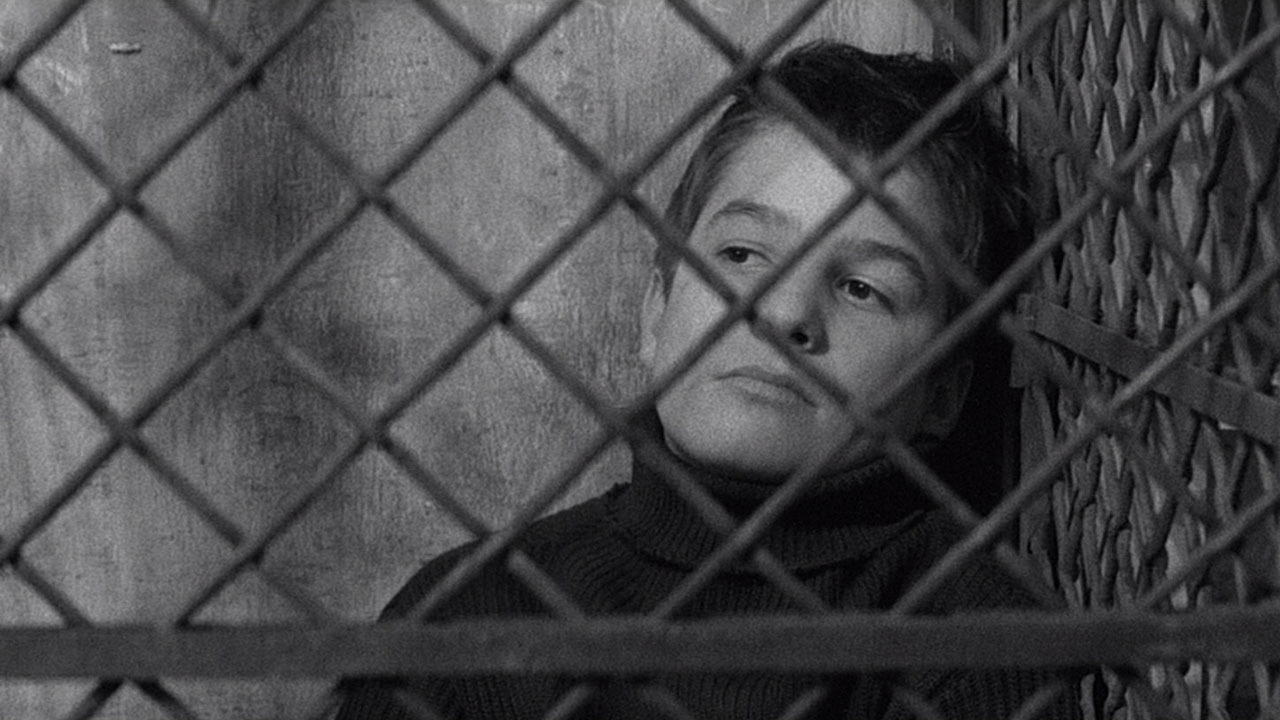

4. The 400 Blows (1959, Francois Truffaut)

That last shot, engraved in the minds of film lovers young and old, is enough to describe the greatness of this movie. On the shore of a tempestuous sea, eerily empty, a young Antoine is turning to the camera, and his piercing stare stays engraved. What is the young man trying to say to us? Is he confused? Is he scared? What future awaits him? Is there a person that can lend him support? Help?

This semi-biographical feature is one of the best representations of the troubling adolescence, that oh so complicated and confusing period. Antoine, played to perfection by the future master Jean-Pierre Leaud, starts the film as an unsympathetic delinquent. As time passes by, the viewer starts to understand the reasons for that.

There is no other way for him, without an authoritarian figure to guide him to better himself. His teacher doesn’t understand and he is of no interest to his own parents, especially his estranged cold mother (later in the film, in a session of heartbreaking interviews, we find out he is a result of an unwanted pregnancy and was saved at the last minute from abortion).

With a total lack of care and with a great dose of anger and confusion, there is nothing else for Antoine than to act toward the world the same way it acts toward him, but due to youthful unwillingness and lack of experience he ends up in a juvenile correction facility, where he gets the same reception. He runs away and ends up on a beach. And cut to black. Stop. What does the future hold?

3. The Young and The Damned (1951, Luis Bunuel)

The slums are a hell from which you cannot escape. You can try, but the consequences are dire. In the centre of that miserable place, the podium is full of kids, adolescents, cripples. The most endangered layer of society. Don’t sympathize too much with anyone – the oppressed can become oppressors in a moment (look no further than the blind beggar Carmelo).

Bunuel doesn’t provide easy answers, he doesn’t provide hope or solitude. The characters who accept fate are chained to that ravine, while the ones who try to challenge the established order end up three meters underground.

In front of you is raw, cruel realism, but when Bunuel uses his mastery – surrealism – that is the strongest symbolism you’ll see. Beware, one wrong display of emotions and you stay trapped in the hopelessness of the Mexican suburbs with a soul covered with blood and sludge, like hundreds of others that tried to find salvation.

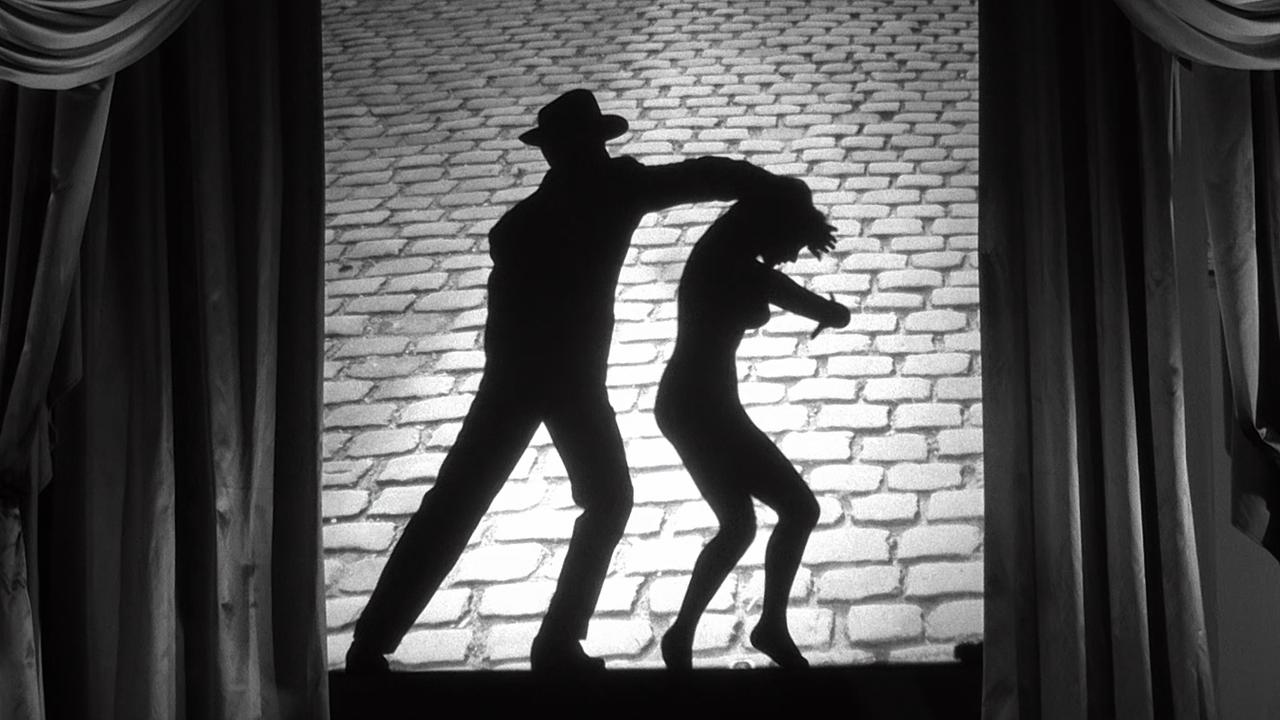

2. Rififi (1955, Jules Dassin)

To talk about this film means to talk about the heist scene. This practice became repetitive and this text won’t break the tradition. How could it? Before you is 30 minutes without dialogue or music, 30 minutes of silence filled with tension, sweat, the ominous ticking of a clock, and the only thing the audience can do is, at the scene’s maximum hauteur, writhe in the “comfort” of their seat. Within that half-hour, attention is given to every single detail (so much so that many real life robberies used the same method).

Blacklisted from Hollywood, this was the opportunity for Dassin to show the middle finger to his former colleagues and bosses. Far away from the claws of the production code, Dassin was able to, in complete freedom, show all the debauchery he wanted.

In front of us we have heroes with all their needs and desires, so we can understand why they put all that effort into the heist, but at the end of the day, they are the scum of society. The people they are going against also exist at the border of what’s acceptable.

The world we are thrown into is covered with grayness. Female characters, even with an unenviable time onscreen, leave an outstanding impression; the story would be an empty shell without their touch. So, viewer, sit tight and enjoy one of the best features of the noir genre, while the silhouettes of black and gray fill the space of a bleak and stuffy Paris.

1. Yi Yi (2000, Edward Yang)

The greatness of Edward Yang is that he is capable of making a film of epic proportions that at the same time feels close and sincere. A spiritual successor to “A Brighter Summer Day,” “Yi Yi” shows that the hard times slowed down, a cultural identity is found, but problems still exist.

Over nearly three hours we follow three members of the Juan family and their ups and downs, happiness and sadness. Yang transitions from one point of view to another with great ease, be it the childlike, still unfazed by life hardships of Jang Jang; the turbulent and unstable of the teenage Ting Ting; or the wise and tired, but confused and uncertain,of the family patriarch NJ; so masterfully done, that the only thing left to do is be amazed by the skills the director had.

We start with a wedding and end with a funeral; the film celebrates an entire life span (like many on the list) and any single moment, no matter how plain and mundane it is, that fills it.

It is an enormous collection of people with their ideas, events, sentiments and relations, but every detail is shown to such extent that with the last clapboard we feel as if we lived an entire eon as the characters we shared all these hours. “This is a magnum opus that never attempted to be one.” Everything works in this film, and that is the reason it took the top position on a list full of cinematic gems.

Honorable Mentions: Red Psalm (1970), A Sunday in a Country (1985), Graduation (2016), Antonio Das Mortes (1968), Caro Diaro (1994), Days of Heaven (1978), L’argent (1983).

Author Bio: Kosta Jovanović is a defectolgy student from Belgrade, Serbia who in his free time (and he has a lot of it, for better or for worse) watches movies from all genres and all countries. While he wants to make films himself one day, for now he is focused on his writing and film critique career.