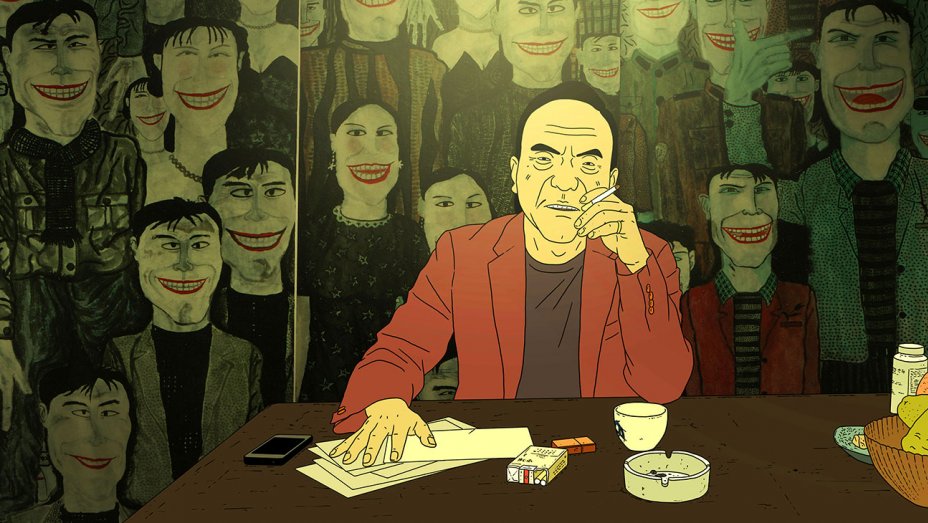

5. Have a Nice Day

When the Academy Awards started recognizing animated features in their own category, there was hope that this would lead to greater attention for animated films worldwide. Unfortunately, barring a few exceptions, that category has remained a typical outlet for western fare, which means that films like Have a Nice Day are invited to the dance but never make it into the building.

Which is a shame because the US doesn’t really make films like Have a Nice Day, that is animated efforts that are distinctly adult stories. Made by animator Jian Liu, Have a Nice Day is the story of a young gang-affiliated driver whose decision to steal a bag of money leads him, his shady industry, and much of his southern Chinese city into chaos. If early 2000s Richard Linklater-in-rotoscoping-mode directed a script by the Coen Brothers, it might look something like this.

Have a Nice Day doesn’t have the most original premise, but Jian uses it to make a second feature that displays the confidence and wit of a daring animator and filmmaker. The film played at the Berlin Film Festival and had its own share of controversy (and name changes) prior to its premier in its native China. But Have a Nice Day should be giving films like Isle of Dogs and Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse a run for their money on year-end best of animation lists.

4. Museo

Mexico had a big cinema moment in 2018 because of Roma, but audiences north of the border typically forget about their neighboring film industry unless the names Cuarón, Iñárritu, or del Toro are bandied about. Luckily for cineastes, however, films like Museo are proof of a vibrant cinema culture.

Director Alonso Ruizpalacios and his co-writer Manuel Alcalá delivered a brilliant entry into the cannon of stories-so-strange-they-must-be-true. Museo tells the true(ish) story of the 1985 robbery of Mexico City’s National Museum of Anthropology.

Ruizpalacios is clearly a student of the greats, and he manages to imprint Museo with a sense of style that is distinct without being showy. His cast, which includes Gael García Bernal and Simon Russell Beale, fresh off his monstrous turn in The Death of Stalin, manage to capture the suspense and sensitivity of the story.

Museo had a slightly publicized bow at the Berlin Film Festival, which (as of this writing) is the most understated of the major film festivals, and the film was appropriately understated. There are few if any Oceans 11 of Fast and Furious hijinks here, and those that do make it onscreen are explored with intelligence and nuance. This is a film called Museo that is about a museum, the robbery of the museum, and the robbers, and it approaches each element with the delicate intensity necessary for masterful storytelling.

3. Thunder Road

In some ways, Thunder Road’s place on this list is also carrying the torch for so many of the films that deserve to be on lists like these but face stiffer and stiffer conversation every year, films like A Bread Factory or Sócrates. These are films that work with budgets below a million dollars, that self-distribute and build their audiences one screening at a time.

Thunder Road may have the best narrative of any true indie coming out of 2018. It started as a short, with director/writer/composer/co-editor/lead actor Jim Cummings crowdfunding his budget to build it into a feature that won the top prize at South By Southwest, became a festival hit, and even found a minor European following.

Of course, this narrative would be moot were it not for the film’s quality and unique voice. Cummings has delivered a dramedy, titled after a Bruce Springsteen song, that could’ve easily been a trifle. A policeman teeters on the edge after personal adversity challenges his concepts of love, family, and self. Fortunately, Cummings realizes that drama doesn’t need to be milked, and he lets what could be a standard indie premise turn into a riotous exploration of how people negotiate grace amidst chaos. It’s a true feat that Thunder Road looks and sounds like a mainstream films but feels unique and different.

It’s also the kind of film that reminds audiences that independent film comes from everywhere. This time of the year is typically reserved for films that have made a great effort to garner attention and, consequently, awards, but Thunder Road is a reminder that the democratisation of filmmaking and distribution has also created a caste system, where filmmakers compete at different levels.

In a time when aspiring auteurs leverage personal, down-to-earth stories for the chance to make big budget CGI-driven fare, it’s important to remember that cinematic magic happens everywhere: in cinemas all over the world, on streaming platforms, at modest film festivals, on demand, and anywhere where people like Cummings believe in their stories enough to will them into existence.

2. Assassination Nation and The House That Jack Built

Dare we include not just a tie, but a tie comprised of two deeply flawed, very imperfect films? After careful deliberation, the answer had to be yes. Both Assassination Nation and The House That Jack Built are over-the-top and yet underrated. What’s more, they both complement each other in their ambitions and results.

Assassination Nation tries very hard to be frenetic and shameless, but it can’t hide its desire to be important and socially relevant. It’s a modernization of the Salem Witch Trials, depicting how a town devolves into chaos once everyone’s online activity is revealed.

When it premiered at Sundance, it sold for $10 million and was a resounding bomb at the box office. Critics were tepid as well, calling it style over substance. They’re not wrong. It’s a trashy film that offers a big moment then retreats into nihilism. But for most of its runtime, it’s also a blast, sometimes literally. It’s hard to remember the last time a film sizzled with the potential for so much chaos, and it delivers in a way that should mostly satisfy anyone drawn to a film titled Assassination Nation.

If the former is a trashy film about serious issues, then The House That Jack Built is a serious film about a trashy—to put it lightly—person. Lars von Trier’s latest takes an artist’s appreciation to murder, specifically serial killing. Audiences and critics cried foul with claims of misogyny, gratuitousness, and self-indulgence not to mention the requisite boos and walk-outs on the festival circuit.

Yet von Trier seems to have put together the most comprehensive dissection of toxic masculinity on screen. He systematically introduces then debunks the excuses society uses to justify the cruelty of men, especially when it’s focused on women. It’s also the first time in a long while that von Trier seems uncomfortable balancing his voices as filmmaker, provocateur, and philosopher, but the result is still rightfully revolting and intriguing.

These films are included on this list, and together on it, because they were met with responses that sold short the craft, control, and depth of each. Both are problematic in most senses of the word, but both have something to say about what it is to be problematic and how society enables that quality while constantly telling us to reject it. There are better films released in 2018, and there are more cohesive films, and more developed ones as well, but there were fewer films as idiosyncratic and misjudged as these two.

1. The Sisters Brothers

Thankfully, Stan & Ollie snagged a BAFTA nom for best British film, otherwise that would make 2 John C. Reilly buddy pictures that went woefully ignored this year. The Sisters Brothers will go down as one of the year’s biggest non-starters, and it enjoyed a level of publicity and a positive narrative that the other films on this list lacked. Despite this, The Sisters Brothers deserved so much more.

A lot of the aforementioned positive narrative was about Reilly, who shepherded the production with his wife and co-producer. The workman character actor making his own roles was just the first part of great press.

Joaquin Phoenix giving another layered performance added to the campaign and put this film on the Oscar map. Bringing in Jacques Audiard, one of the most respected filmmakers in the world, to make his English debut only whetted appetites. All of this was sunk by dismal box office and critical notices that were so good that critics spoke admirably of the film but ignored it to tout their Oscar favorites.

But all these things don’t say much about a film that is smart, funny, and among the best of the year, even if it is at times a little too familiar. Few films in any year manage to be as cohesive and fully-formed. Reilly anchors the film, giving another generous performance that foregrounds Phoenix’s odd charisma. Riz Ahmed and Jake Gyllenhaal turn in fine performances.

As director and co-writer, Audiard controls the proceedings masterfully. Foreign directors, especially European ones, often lose themselves in Hollywood. Just look at Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck and Oliver Hirschbiegel, but Audiard retains his wit and keen eye while telling a distinctly American story.

Alas, audiences enjoyed Reilly as part of a two-hander, just not here. Brits had plenty to love as he added prosthetics and weight in Stan & Ollie, acting opposite Steve Coogan. US audiences ate him up opposite Will Ferrell in Holmes and Watson. It’s a shame they completely ignored this effort.