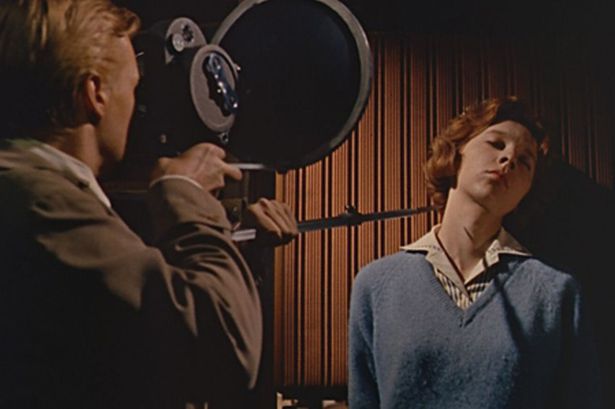

6. Peeping Tom (1960)

Peeping Tom is one of the most influential, yet least discussed horror films ever made. Its pioneering techniques created not only the basis for the “slasher” genre, but also introduced some of the most complex themes to be presented on the big screen. The central character, shy and reserved Mark Lewis, murders women to record their faces of terror moments before death.

When he befriends a young woman named Helen, the horror begins to unfold — Mark, haunted by the experiments his father forced him to participate in as a child, plans to make his own documentary with the footage he takes. Chilling and dark, the use of the self-reflexive camera fully immerses the audience in the horrific events taking place on screen.

Michael Powell’s Peeping Tom is frequently compared to the masterpiece of another auteur — Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho. Both films feature a young man scarred by family trauma as well as a beautiful woman as the victim. Both are praised for their psychological depth and complexity. Additionally, both were released in 1960 with the latter, Psycho, coming out just two months later.

However, while Powell’s film was banned in various countries after its premiere in the United Kingdom and his career was negatively affected by this setback, Hitchcock’s film was immediately praised following its premiere in New York. Though this could be a result of the graphic deaths in the former work, it also reflects many of the tensions in Britain at the time. The English press was not offended by the striking visual imagery, but the perverse nature of the themes explored.

Despite making some of the most acclaimed films in history including The Red Shoes and A Matter of Life and Death, Michael Powell’s career was ended by the overwhelmingly negative reception to Peeping Tom.

However, nowadays, it has not only established a major subgenre of horror, but also become an important classic in British cinema — as Powell expressed himself, “I make a film that nobody wants to see and then, thirty years later, everybody has either seen it or wants to see it”. For both its artistic brilliance and polarizing effect over time, Peeping Tom remains a must-watch for aspiring filmmakers and horror fans everywhere.

7. Blind Chance (1987)

Written and directed by Polish auteur Krzysztof Kieslowski, Blind Chance presents three scenarios to a simple action — as a man runs after a train, three different outcomes of the situation are presented. In each, his reactions to the people around him as well as whether or not he successfully catches the train influences the sequence of events that follows.

Even though the initial incident seems mundane, Kieslowski demonstrates its weight with the chain reactions that follow. However, despite the various storylines, each end in complete disaster: perhaps Kieslowski is expressing that no matter what, we cannot escape our fate in the end.

Besides its commentary on the concept of fate, Blind Chance also criticizes the political climate of Poland in the 1980s. The narrative of the film reflects the tense state of the country under Communism and the people’s reaction to it — in one scenario, the main character even joins the Anti-Communist movement to overthrow the government. Even the rest of the storylines reflect this sentiment with elements of political disorder present in each.

Unfortunately, this was what caused the film to be banned for about six years and the full version was not seen in its entirety until the Criterion Collection restored it. However, despite the cynical nature of the plot, Blind Chance is a humanist look at the concept of choice on both a broad and personal scale.

Though not as well-known as The Three Colours Trilogy or The Double Life of Veronique, Blind Chance is still an extremely influential film with effects on cinema that are still present today. Sliding Doors and Run Lola Run are two of the most obvious examples of this, but others, such as Mr. Nobody, also explore similar narratives.

Even if Kieslowski’s film is heavily imbued with commentary specific to the Communist government of Poland, it contains universal themes that are accessible for every person. By questioning what could have happened, Blind Chance leads us to reflect on our own actions and the course of life we are on.

8. Zulu (1964)

Among the great war epics memorialized today, Zulu is rarely mentioned despite being one of the most grand and brilliant. Directed by Cy Enfield and featuring Michael Caine in his first major role, the film depicts the Battle of Rorke’s Drift, a battle of the Anglo-Zulu War during which 150 British soldiers were able to defeat 4,000 Zulus.

The film is praised for being a mostly historically accurate account of the Anglo-Zulu War, which was fought between the British Empire and the South African Zulu Kingdom. Zulu does not contain any political messages or contrived storyline — instead, it is an authentic look at a major turning point in history.

One of the most admirable aspects of Zulu is that it did not present any recognizable bias. Throughout the film, neither the British or the Zulus are portrayed as the antagonists. This increases immersion for the audience, as the film does not showcase the glorification of war, but the brutal reality.

With some of the greatest battle sequences ever put to the film, the only issue of Zulu is how realistic it looks — subsequently, it was even banned in South Africa under Apartheid for showing a Zulu uprising. Ironic to the film’s original anti-imperialist message, only Whites were allowed to see it in their segregated theaters.

Today, Zulu is considered to be one of the greatest films in British history. However, the film is not as well known to the rest of the world — this could be due to various reasons, such as its premise stemming from a historical event not widely studied or the censorship following its release.

Either way, it is deeply unfortunate as there are so many parts of Enfield’s film that filmmakers everywhere could learn from. The accurate depiction of class struggle, rounded perspectives, and moralistic viewpoint make Zulu one of the most technically and culturally progressive war films in cinema history.

9. WR: Mysteries of the Organism (1971)

Released in 1971, WR: Mysteries of the Organism was directed by Serbian filmmaker Dušan Makavejev, one of the most notable directors of the Yugoslav Black Wave. Juxtaposing footage from various documentaries with striking visual imagery, Makavejev presents an artistic but brutal look at both the communist regime in Yugoslavia and the concept of government itself.

He also explores the controversial work of Wilhelm Reich, an Austrian psychoanalyst best known for his theories which use human sexuality and emotion to understand totalitarian and fascist regimes. The film, which utilizes characters to represent abstract concepts, defines revolution on both an individual and universal spectrum.

Unsurprisingly, due to its political contents, Mysteries of the Organism was banned in Yugoslavia for 16 years under Fascist dictator Josip Broz Tito’s Communist regime. In addition, Makavejev was indicted on criminal charges after commenting on the ban to a West German newspaper. He was even exiled from the country until the end of the regime.

Though his film was praised at the 1971 Cannes Film Festival, only a select number of moviegoing audiences were able to see it in the years that followed. Mysteries of the Organism is important not just for its innovation in filmmaking, but also its ambition in demonstrating the flaws of the corrupt regime of the time.

Mysteries of the Organism features clips from Nazi and Stalinist propaganda films and footage from the according regimes. Its Western sequences present a multitude of artists, such as Betty Dodson and Jackie Curtis, that epitomize contempt for society’s rigidity in politics and sexuality.

The polemical defiance of the film appears through both its contents and its experimental style. Radical and brilliant, Mysteries of the Organism is a keystone of revolutionary cinema that to this day, serves as a reminder of the relevance of art in society.

10. Ciguli Miguli (1952)

Directed by Croatian filmmaker Branko Marjanović and written by Joža Horvat, Ciguli Miguli is one of the most original and impassioned examples of political satire. In the film, a bureaucrat named Ivan Ivanović arrives in a small town as a replacement for a local official.

He is adamant to instill the town with socialist ideals and to achieve this, he begins a series of dramatic reform including abolishing all five of the music societies and ordering the destruction of the city’s most important monument — a statue of the town’s most respected native, the late composer Ciguli Miguli. However, instead of succumbing to his authority, the townspeople come together in revolt, exhibiting the unity and determination of the human spirit.

Ciguli Miguli is the second collaboration between Marjanović and Horvat — the first being the 1949 realist war film Zastava. For the latter, the artists believed that satirizing the Socialist regime of Stalin would complement the liberalization in Yugoslavia following the Yugoslav-Soviet or Tito-Stalin split in 1958. Moreover, they were hopeful that their film could potentially catalyze this return to democracy.

Because of Horvat’s affiliation with the Yugoslavian Communist Party officials, the censorship and negative reception to the film were completely unforeseen. What the filmmakers had not realized at the time was how relevant and pertinent Ciguli Miguli would be to Yugoslavia’s government in the years to come.

Despite its fictional premise, the implications Ciguli Miguli placed upon society were scathing. Upon its first screening, government officials were immediately offended by the simple minded and unsophisticated portrayal of the Socialist bureaucrat. It was rumored that even the party’s leader, Josip Broz Tito, was angered by the film, which led to its subsequent ban. Its first public screening was in 1977, twenty-five years after the original release.

Though the filmmakers were not aware at the time, it foreshadowed the future of the Communist regime and its effect on society — for both its insight on government and its historical significance as the first Yugoslav satirical film after World War II, Ciguli Miguli represents the importance of solidarity, especially in the face of corruption.