Films raise questions on a various means in style and content. However, certain films specifically challenge your intelligence while the filmed is screened in front of you or after the end credits. It assaults what you actually know or thought about beforehand and can alter your way of thinking or how you approach certain things afterward.

There is a difference of raising a question, such as, who was the murderer? What really happened at the end? Was it all a dream? But when a film resonates in your experience and you have to do research or look up the filmmaker’s intent if you can find it, or read books on the subject that was explored, you can say it challenged you in a way that most films don’t.

Therefore, here are 10 films that puzzle, ponder, and spark questions beyond the mere brain-thinker of a film.

10. Schizopolis (1996) – Steven Soderbergh

A filmmaker who knows no bounds regarding whether to dip his toe into experimental cinema, iPhone filmmaking, Hollywood, and more; the non-actor stepped in front of the camera literally stating, ‘“n the event that you find certain sequences or ideas confusing, please bear in mind that this is your fault, not ours. You will need to see the picture again and again until you understand everything.” Well, that’s that.

The film explores duality in the home and workplace through doppelgangers and an assortment of ideas that even Soderbergh inserted on cue cards reading ‘Idea Missing.’ It truly is a film to behold because it reinvents itself as though the filmmaker was almost every few minutes creating something that is never dull.

To comprehend this, you might need to study Dostoevsky or Stephen King to see what doppelgangers represent, and more importantly, mean to us. Is there a replica of us out there? Or is this just a dream world we inhabit? Or are we so insignificant that we can’t communicate? Is this maybe that’s what Soderbergh was trying to do on a cinematic low-budget level? Well, it looks like he achieved that and we’ll be wondering how for years to come.

9. Inception (2010) – Christopher Nolan

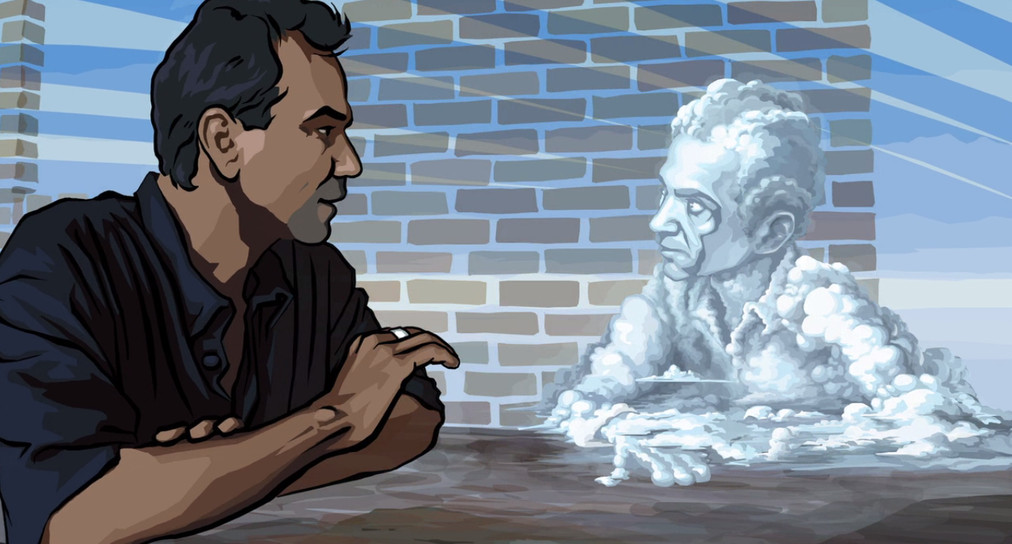

In this film, Christopher Nolan verbally and visually explores the world of the dream within other dreams. His characters float around in their subconscious and others, create new worlds and meaning, and strive for their best lives. However, it’s not only after the action-thriller-mystery is complete that we really begin to question how smart we really are.

There are numerous references in the film, such as the penrose stairs. But take how his characters then explain the factual evidence of the dream due to the illusion, senses, and what they are telling themselves. Its a unique approach because Nolan states and then explains, making us wonder what this is about, such as the illusion of making an actual film.

Nolan best explains it himself when he stated he wanted to explore “the idea of people sharing a dream space that gives you the ability to access somebody’s unconscious mind.” Therefore, is this possible? Could it be a reality? Or a reality where we truly live in our own world?

These questions have been consistently brought up as well as the ending, as though were actually all a dream. However, while we might dream the same way after seeing this film, the exploration of the meaning of it has been altered and changed.

8. The Milky Way (1969) – Luis Bunuel

Luis Bunuel was never shy of controversy, absurdism, or trying something new throughout his varied career. In his 1969 film “The Milky Way,” he tackles religion once again but presents an argument where all sides can be heard. Usually, such as in “Viridiana” or “Simon of the Desert,” Bunuel will lean heavily on one side, attacking the structure and morality of religion, but here he presents both sides of the coin.

From every instance that comes in the film, as the pilgrims travel to Santiago de Compostela, there is an individual or individuals that challenge the other. When one makes a point of Jesus, Catholicism, or the practice of the Christian faith, it is immediately counter-argued verbally and visually through Bunuel.

This makes the audience think about which side is correct and form their own argument. And Bunuel never shies away from his absurdity, such as Jesus contemplating a shave or rosary beads being shot at. He never loses his sense but allows the audience to find that sense.

This can be one of Bunuel’s most challenging films because of seeing both ends of religion. When every character speaks their rhetoric, it makes sense and we are the ultimate deciders on what is true and what is faith.

7. Primer (2004) – Shane Carruth

A film where writer, producer, actor, composer, editor, and director Shane Carruth wanted to strip everything down to the bare minimum for his time-travel film. Yes, on a budget of $7,000, he created a film that no matter how many times you see it, you get lost along the way. But you also always manage to come back to it for several reasons.

The approach of the narrative, consistently jumping around and never knowing what is present or the future or the self they are in, presents us first with the story. And second, this leads to the atmosphere of the film in which the creator never wants to over-explain or even allow the audience to catch up or comprehend.

The dialogue is delivered so flat and mundane on other worldly subjects, such as the electromagnetic reduction of an object’s weight to time travel to the Meissner effect.

Carruth was purely obsessed with his ideas and never compromised his vision, and as a result despite it being a lo-fi film, he created a film with unending questions of logic and scientific portions that audiences are dumbfounded on what actually occurred and what was discovered, literally.

6. Fight Club (1999) – David Fincher

A film where Chuck Palahniuk, the author of the novel by the same name, stated that the film “elevated” the original book. This could be seen in the attack of capitalism, the explicitness of consumerism, or the dissociated personalities of our leads or lead. It’s what the film represents, where we ask ourselves questions on a existential level, like, “Who am I?” to “Am I that everyman too?” that leads to a psychological analysis of ourselves.

Fincher didn’t shy away from his storytelling or obsessive details, but out of this he managed to create a film where the viewer has as many questions as Tyler Durden and/or the Narrator. We are in a constant state of questioning what is or what was real. But more importantly, you question if you are capable of going down this spiral of madness because you might be that ‘everyman’ too. Maybe it’s not as heavy as a split personality, but the emotions of anger, fear, and loneliness that can push us to the edge is what makes this film resonate today, and continue in pop culture and film studies classes.

Numerous commentary has been associated with “Fight Club,” ranging from European fascism to slumming trauma. Whatever one’s interpretation and critique of the film, it’s always a unique angle from one original source.