How were film genres created?

Through the more recent decades of cinema, it has become increasingly common for films to blend elements of different genres in order to tell unique, eye opening, and sometimes disturbing stories. Part of what makes a film “defy” its genre is the director’s innovative use of cinematography and musical score. However, another key aspect is the content matter in which it chooses to address. The more freedom a director has to be truthful through their lens, the more likely they are to use unconventional approaches in order to trigger a certain level of awareness in the viewers.

Film genres, like music, change and transform over time. They use recycled inspiration in order to create new forms of execution.

These 10 movies are amongst those that have evoked a certain level of rebellion through their mixed styles. As they searched beyond the structures of genre, the directors mentioned below have opened avenues of hybrid genres, and challenged the norms of what is allowed to be addressed on film. They changed the rules by breaking them.

1. Koyaanisqatsi (1982, Godfrey Reggio)

Koyaanisqatsi is the Hopi word for “life of moral corruption and turmoil” or “life out of balance.”

There is no experience like viewing the history and destruction of the Earth happen in front of your eyes. Through a compilation of videos sewn together by an epic and repetitive score, Koyaanisqatsi is terrifyingly indicative of the manufactured world that humans have created from the Earth’s resources. Although it takes patience and a deep concentration to watch, no one can come out of seeing Koyaanisqatsi the same.

Essentially, it has no genre. It is a series of images that navigates you through a plotless, characterless journey of nature’s progression through time. The film feels like a documentary at times, however only partially, because the lack of narrator or direction eliminates the rhythm of a documentary. It is difficult to describe the experience of Koyaanisqatsi as anything other than moving.

It is a film intended for complete surrender and immersion into the rhythmic forces of nature, with the conflict being humanity’s interruption of it. Koyaanisqatsi is not a symbol of protest. It takes viewers into the visual experience of human pollution much rather than the lesson. If we look deeper into what Reggio intended, it was to use technology to spy on nature, before and after the human conquest of it.

As a result of its rebellion in regards to its lack of clear structure, Reggio still managed to a create a rhythmic piece of art that is effective beyond the structure of film itself.

2. Gummo (1997, Harmony Korine)

What makes Gummo particularly unconventional is how the film alternates from messy home videos to shots that seem like they are following several different characters in a documentary styled film. It’s important to note that it isn’t labelled a documentary, although it feels that way a lot of times. The film also turns cinematic at random points, where music and slow motion effects intensify the experience. Apart from its lack for a clear narrative or any main characters, the film is also unconventional in its brutal transparency.

Gummo is a set of stories and images that together create an experience like no other film. It follows children and adults throughout their daily activities around the tornado stricken, impoverished community of Xenia, Ohio. A few of their activities include abusing animals, sniffing glue, taking baths in green brown water, and the unfortunate occurrences of child prostitution and incestuous rape. Korine gives us a tour of the physical and psychological devastation of the town through their rituals of cyclical violence.

The home videos are particularly effective in enhancing the honesty of the film, as they often recount stories of abuse, suicide, or cross dressing. They give the film a brutal awareness as to why Xenia seems so damaged from an outside perspective. There is a necessary sense of confusion throughout the mixture of home videos and film shots that blends the people’s emotions.

The film tells the story of the town of Xenia as a product of the people, a character in and of itself that is affected by both natural disaster, and the emotionally destructive families inhabiting it. As a result, Gummo is a mirror to the provocative and horrifying realities of the citizens of Xenia.

Through his unstructured use of shots, stills, and sounds, Korine’s Gummo presents a vivid realness to the hopeless people of Xenia, trapped in cycles of poverty and psychological abuse.

3. Tangerine (2014, Sean Baker)

Tangerine is a film about two transgender women, Sin-Dee and Alexandra, on a mission to find the woman Sin-Dee’s man has been cheating with while she was in jail. Along this wildly dramatic mission, which Baker shot entirely on an iPhone, we are taken through the ups and downs of relationships in a Los Angeles neighborhood that is fueled by prostitution.

The film begins with Sin-Dee and Alexandra talking back and forth in what becomes a heated realization of her boyfriend’s infidelity. The first scene alone exudes the eccentric, moneymaking female energy of reality TV. Along with the unnecessary drama of the plot and characters, the film’s colour grading drenches the screen in a yellow saturation that is equally as extreme.

The music is another confusing element of the film, flipping from EDM, to classical music, to intergalactic hypnotic beats, to post-hard core dubstep, to alternative rock, and back to Armenian EDM music. That’s the genre bending nature of the transitions in Tangerine.

Through the familiar turmoil of love and friendship, the film presents two outcasts of society in a way that feels truthful, giving them a platform to be unapologetically themselves. There is an individuality and purity to their drama that seems a necessary tool to cope with their struggling lifestyle, which is regarded but never dramatized in a way to trigger pity. The film presents a world where they fit in, and are not looked at funny for who they are. However, it’s important to remember that they represent a subculture in the America they live in.

In that regard, Tangerine premiering at Sundance and getting international praise was a major step for transgender representation on film. It also carried with it the hope that anyone with a raw story to tell and a mobile phone can make a film.

Tangerine is a concoctive blend of drama, tragedy, and comedy, feeling unapologetic and outrageous in its choices of plot, characters, camera shots, and musical score.

4. Irréversible (2002, Gaspar Noé)

Irréversible is arguably one of the most difficult films to digest in cinema history. The story follows a man named Marcus who is looking to avenge his girlfriend Alex’s death. Alex was found severely beaten and raped in a metro station that same night. The film leaves no details to the imagination, and displays long, chilling scenes of uncut violence and abuse.

What makes the film even more unique is the chronology of events. Noé took the natural structure of storytelling within the thriller genre, and redefined it as his own by beginning the film with the end, going through the story backwards. As the title implies, Irréversible presents the irreversible damage of violence before we even know who and what happened for there to be any conflict at all. One clear intention that the director had when shooting these different events was to reverse the standard progression in which emotions peak and fall in a film.

Irreversible is a psychological thriller that in it encapsulates drama, romance, crime fiction, action and mystery. By displaying horrific acts of rape and violence on a film screen, using uncomfortable spinning camera shots, and executing the story on his own terms, Noé’s film redefines the thriller genre, and creates an entirely new panic fueled energy in cinema. The way the pieces of the story are put together is so unique and haunting, that it is surely going to keep shocking generations of viewers to come.

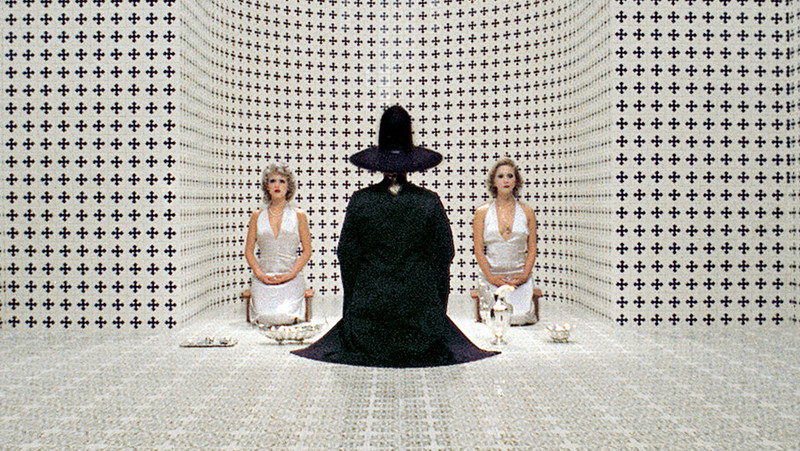

5. The Holy Mountain (1973, Alejandro Jodorowsky)

Equipped with thousands of strange, surreal, and scarring images, The Holy Mountain can be considered a shock therapy film. With eye opening, philosophical intentions, of course.

At its root, it is a fundamental story of self-actualization in a highly manipulative environment of debauchery.

The film adapts into science fiction when we are introduced to the powerful politicians that rule the other planets. Amongst these planets are leaders performing tasks such as manufacturing faces, brainwashing children to destroy enemies of war, making sporadic decisions to murder innocent people in order to restore the balance of economics, mass producing decorative war weapons, or creating sexually interactive art.

The film regards themes of political power, moral corruption, religion, alchemy, and enlightenment through images of religious iconography, nudity, insects, animal abuse, and colour. At times, the extreme images presented are so absurd and violent that there is only a triggered reaction, and no rational explanation for what is being seen. It’s possible that Jodorowsky’s message is that there exists corruption that must be seen to be felt, but that none of it really has a meaning. One must have the patience to go through their own personal journey in order to define its meaning.

Aesthetically, it’s a surreal masterpiece. Some may refer to it as a horror fantasy, seeing as many of the images are difficult to watch. In terms of the plot, it is a tale of self-discovery following in some ways the structure of a science fiction film, where dystopic realities co-exist with the present day to feel eerie and dark.

The extent to which Jodorowsky experimented with the visuals of the film, is equal to the philosophical reach of the self-reflective end. When the fourth wall is broken, we realize that this newly boiled up blend of genres is simply part of an ambitious attempt to be profoundly moving.