Cinema is still an early art, but is one of the most rapidly changing forms today. You no longer need a huge magical box to create a movie, just a few collaborators, or even just one on your smartphone. Therefore, new ways of storytelling from around the world are constantly put into the realm.

Thus far in the 21st century, there have been dozens of films that changed the form of narrative, challenged the form, or have done something completely original. Here are 10 films that did just that.

1. Werckmeister Harmonies (2000) – Bela Tarr

Up to this point, Tarr was known for his seven-hour epic “Satantango.” In 2000, he made a black-and-white film composed of 39 shots that showcased the Slow Cinema movement. Yes, films that experiment and show the passage of time have existed, but not in a deeply philosophical and lyrical way.

The film is still open to many interpretations, from the planets aligning to the critique of Eastern Europe’s political systems following World War II. Regardless of what actually aspires in this town and its giant, dead whale at its center, the film is hypnotizing to the viewer due to Vig’s haunting score, numerous cinematographers, and Tarr’s direction. He changed the way cinema could present a story in swooping camera movement, such as the films of Angelopoulos but with a more universal approach of storytelling.

Tarr has retired from filmmaking, but with “Werckmeister Harmonies” it seems new every time and inspired filmmakers such as Gus van Sant to tell stories in a new way.

2. This Is Not a Film (2011) – Jafar Panahi

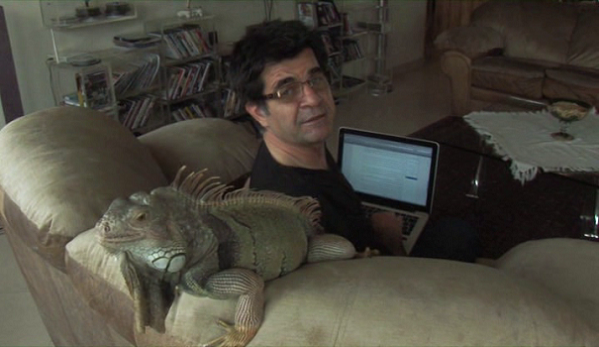

Despite the fact that Iran has sentenced Panahi to house arrest and a 20-year ban on filmmaking, this didn’t stop Panahi from creating. In 2011, this ‘film’ was smuggled to Cannes on a flash drive inside a birthday cake, showcasing an absorbing look at a filmmaker’s drive to create and a reflection of filmmaking itself.

The film takes place in Panahi’s apartment, all filmed on an iPhone with the assistance of Mojtaba Mirtahmasb to detail his life since being under house arrest. Throughout the film, Panahi addresses his current state, talks about films, the film he wants to make, and what will happen.

This film could not have happened with the use of smartphones and today’s technology. Regarding the title of the film, one can decide what this truly is. Is it a narrative first person approach, one long interview via documentary, or a critical on a filmmaker’s life? As the credits roll, we see that we truly experienced an artist’s point of view and introspection on his films, country, and self, proving a new form of storytelling.

3. Hunger (2008) – Steve McQueen

Steve McQueen was a distinguished artist before diving into cinema. He explored various forms to include arthouse experimental shorts. However, in 2008, he changed the way stories are presented through visual lyrical poetry and dialogue.

Most of the film is a lyrical, elliptical, brutal poem of images and sounds. We never truly see Michael Fassbender’s Bobby Sands for much of the first half of the film.

Therefore, he explodes when we get a 17-minute uninterrupted static dialogue shot followed by a eight-minute close up on Fassbender opposite Liam Cunningham. McQueen uses silent situations, verbose dialogue, harsh sounds, and brutal imagery to create an absorbing film with a political and social message.

Even the last moments of the film remind us of a poem being written before us, but only through the cinematic language of narrative, camera movement, and sounds in a metaphysical and poetic way. McQueen truly brought his artistry to life with his narrative debut and continues to do so.

4. To the Wonder (2013) – Terrence Malick

Sweeping camera movements, lyrical music, and a poetic voice-over is how people describe the aesthetic of Terrence Malick’s films today. However, he was constantly moving in a new direction for his last three films, beginning with “To the Wonder.”

Malick here abandoned narrative, and his male protagonist is a silent man roaming the streets and fields in a midlife crises of sorts, with women involved at its center. This is where the modern Malick was born.

Whether admiring the actors in his semi-autobiographical story, Lubezki’s cinematography, or Townshend’s score, you see things Malick has touched upon before through montage or brief moments, but never to the extent of the entire narrative film. Critics and audiences were somewhat baffled and annoyed by his experimental full-form approach. However, this is the work of a great artist expanding on the possibilities of cinema after several masterpieces.

5. All These Sleepless Nights (2016) – Michal Marczak

A film that is technically a documentary but fuses the lines between reality and fiction – it is really up to you to decide. Sure, films have explored this notion and combine, re-enact or mix up the genre, but Marczak creates hybrid storytelling in his own way.

Developing special tools and a mobile crane lift for the cameras to float around two young male friends partying in Warsaw creates a stranger, outer-worldly yet familiar atmosphere on this quest for self-discovery amidst hedonism and the search for love.

For the people in front of the screen, there are no phones or computers for its leads, showing how individuals can truly live in the moment. For the people behind the screen, this goes against small iPhone cameras or staged cameras for party scenes or social media obsession.

Marczak’s intent and technical approach proves how cinema can be visually stunning, completely real, and emotional engaging without ever losing sight a film’s themes, characters, and meanings.

6. Kaili Blues (2015) – Bi Gan

A film talked about due to its 40-minute tracking shot and spiritual journey into the past, present, and future. Bi Gan’s directorial debut is a fever dream where the audience never really knows or comprehends what’s going on and why. However, that might be Gan’s approach because his characters float in this dream world, as do we.

Gan seems to create a film based entirely from his own mind, thoughts, and beliefs, much like Tarkovsky or Dreyer. He’s more concerned with visual photography and poetry (both areas where he has also expressed himself) in terms of cinematic language. It’s relevant when we switch cameras and aesthetics into a 40-minute tracking shot that seems flashy or excessive, but we are just thrown along for the ride.

Gan’s dream of a film definitely needs to be rewatched, not only to understand what is going on but to enter his dream again, proving that cinema is and can be a dream as long as the dreamer takes you there, thus being Gan himself.

7. Tangerine (2015) – Sean Baker

A film that people call “that movie made on an iPhone.” However, Baker’s film is a tight narrative with exploding characters in a world of Hollywood that we’ve never seen. And yes, the iPhone is gritty, mobile, and specific with this film. Baker started an unconscious movement proving that iPhone filmmaking is worth the pursuit.

The films follows two transgender sex workers over the course of Christmas Eve with interweaving characters. Since it was the first well-known film made on an iPhone, we can see how Baker changed up the filmmaking approach. He was able to go into physically difficult positions, allowing the actors and real-life people to interact because they didn’t know it was a movie, and create an energy that dazzles off-screen.

The film proves that despite a low budget and no fancy equipment, audiences and critics care about what’s in the frame and their emotional connection to it. This film inspired several others to start using the iPhone for narrative filmmaking, such as indie maverick Steven Soderbergh.

8. Russian Ark (2002) – Alexander Sokurov

The first true film that was filmed entirely in one tracking shot. Sokurov proved right before the digital revolution that a film could be made in one take and present a story interweaving time, characters, and art.

Filmed on a Sony HDW-F900, the camera takes us through the Russian State Hermitage Museum with figures over the centuries popping up. However, critics and audiences always talk of the style, but it’s the content that allows the viewer to enter into a dreamlike state inside a museum. The costumes, music, and colors allow us to see a film with no major characters, just for the sake of filmmaking.

It’s easy to say Sokurov inspired many films such as “Birdman” or “Victoria” and films to be connected in one seamless shot, but Sokurov will always be number one, experimenting to make a film in one true take and actually achieving it with dazzling results.

9. Boyhood (2014) – Richard Linklater

Richard Linklater has always been obsessed with time and cinema. Here, he creates, contemplates, and observes these two forms in one film. Having filmed a couple of weeks every summer over the course of 12 years, he created something that no other film in the history of cinema has done or dared to repeat.

The story is fairly simple, as we observe a boy’s life from age 6 to 18 with his sister and divorced parents. The film is simple in its approach as well, with Linklater simply following the lives. There’s no flashy camera gimmicks or transitions.

We continue with the film as the characters do in their lives, growing, aging, learning, and experiencing life. Linklater’s independent form truly paid off by patience and observance, proving that cinema is truly a time capsule of capturing life’s evolution over time in fictional storytelling.

The only other work that can be compared is the documentary ‘Up’ series; however, Linklater’s masterful storytelling of the banality and everyday occurrences in one’s boy life captured on celluloid is truly one of its kind.

10. Goodbye to Language (2014) – Jean-Luc Godard

One of the pioneers of cinematic language, Godard has been constantly challenging the form since 1960. Ranging from the New Wave to Dziga Vertov, Godard has always been changing style and content. In this century, he’s done forms of visual , mixing all the elements to create something new such as “Film Socialisme” or “In Praise of Love.”

In this film, the only motif is a naked couple arguing, reminiscent of his early films, and it is juxtaposed with images of dogs, classic films, voice overs, etc. We never truly understand what is being said or expressed, but that’s Godard’s point, hence the title of the film. And above all, it’s in 3D, shot on various small digital cameras. Godard was going against all types of filmmaking while commenting on the state of cinema by either endorsing it or criticizing it.

Regardless of what critics or audiences think of Godard’s new approach to cinema, he has been constantly changing the form since his first film, and especially in this experimental, non-narrative 3D film.