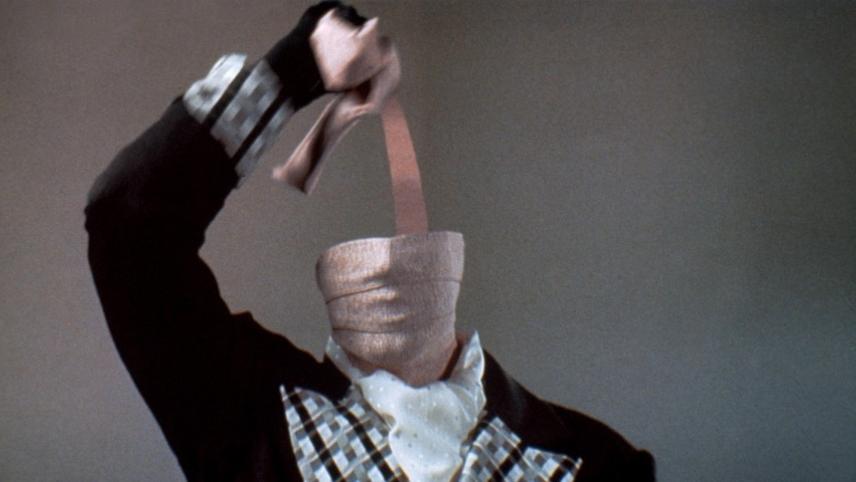

5. Memoirs of an Invisible Man (1992)

A true rarity in the John Carpenter canon, this 1992 variant on the H.G. Wells classic––though truthfully this film springs from H. F. Saint’s playful 1987 thriller novel of the same name––Memoirs of an Invisible Man is largely a comedy with some sci-fi thrill accoutrements thrown haphazardly into the mix.

Originally, as in Saint’s source material, Carpenter and the film’s star Chevy Chase were interested in making more of a suspense thriller with comic elements only on the periphery, but due to studio meddling resulting in Carpenter’s loss of artistic control, Warner got its way and the film is more audience-friendly and far less challenging than the director envisioned.

Average businessman Nick Halloway (Chase) is unwittingly caught in an experiment gone awry during a meltdown at Magnascopic Laboratories. Accidentally endowed with invisibility, Nick needs the help of his kinda sorta new girlfriend Alice Monroe (Daryl Hannah). A charismatic TV documentary producer, Alice may well be the only person who can help Nick out of his nightmare scenario, or at least help him get some answers while avoiding a sketchy CIA operative named David Jenkins (Sam Neill).

Some excellent special effects, some clever wrinkles on the perils of being invisible, and some strong, though often hammy, performances are what make Memoirs work, but that it all plays out rather conventionally and frequently feels like a vanity project for Chase is what prevents it from meeting its full potential. It’s too bad so many elements work against it but it still must be said that the mischievous Memoirs of an Invisible Man is worth seeing (dreadful pun intended).

4. Quintet (1979)

Robert Altman’s deliberately paced and altogether artful post-apocalyptic sci-fi tale confounded critics and audiences on its initial release, and it’s a crying shame that begs the question: can a reassessment be far behind for this overlooked gem?

Set in the distant future, during a new ice age, Quintet features an A-list international cast that includes Paul Newman, Bibi Andersson, and Fernando Rey, each vying for a meaningful life in a landscape of desolation and uncertainty. In a world buried beneath endless snow, the few survivors scavenge for what little food remains, journeying vast distances and ultimately ending up at the Hotel Electra where a deadly five-sided board game, “Quintet” is played.

In keeping with similar works from this period, specifically Images (1971) and 3 Women (1977), Altman instills a subtle greatness and obscure-yet-ever-building tension amongst these characters, their dreamlike environs, and a plot that is frequently clear as mud.

Quintet is a challenging watch, but a rewarding one for the patient viewer or those who enjoy the mysteries of a Möbius strip film, where the meaning must be puzzled out, wrestled, tamed, dissected, and discussed.

3. Slaughterhouse-Five (1972)

Fans of Kurt Vonnegut’s satirical postmodernist anti-war novel from 1969 have, sadly, never exactly been ecstatic over George Roy Hill’s ambitious cinematic adaptation, which eschews a great number of details––including the iconic character Kilgore Trout––but if you can forgive these diversions, Hill has offered up a honey of a film, and one deserving of the Prix du Jury it was awarded at Cannes in 1972.

For what its worth, Vonnegut was very enthusiastic with the finished film, fully endorsing the project and even writing about it in the preface to 1972’s “Between Time and Timbuktu”, which was published shortly after the film’s release. Here Vonnegut writes; “I love George Roy Hill and Universal Pictures, who made a flawless translation of my novel Slaughterhouse-Five to the silver screen […] I drool and cackle every time I watch that film, because it is so harmonious with what I felt when I wrote the book.”

Billy Pilgrim (Michael Sacks) is a WWII soldier who has become “unstuck in time” and director Hill has made certain to pack as much poignant imagery, emotional resonance, and haunting heartache––immeasurably aided by Glenn Gould’s ivory-tinkling score––resulting in what’s certainly the best Vonnegut adaptation to date.

2. The Zero Theorem (2013)

In a deeply dysfunctional world to come—one of the dystopian stripe that Terry Gilliam does so well—the wear and tear of avarice and consumption has replaced religious doctrine, spirituality, and myth in The Zero Theorem. Featuring Christoph Waltz as our hangdog hero, Qohen Leth, he manages to bumble his way through the Byzantine prismatic yet perverse city streets of this imagined future, bombarded by interactive advertisements trumpeting the Church of Batman the Redeemer amongst other perplexities.

A tragicomedy all through, The Zero Theorem concludes the satirical “Orwellian triptych” that began in 1985 with Brazil and recommenced in 1995 with 12 Monkeys. And like those apprised works, this is an atypical Gilliam film that challenges, accosts, and rewards the attentive viewer while certainly alienating those looking for a meagre quick fix.

Qohen, like Sam Lowry before him in Brazil, sweats it out in a serpentine civil service, distracted by feckless superiors (in this instance, an awesomely inept David Thewlis), and gossamer dream goddesses (Mélanie Thierry). Other surprises that surface in the film include Qohen’s constant psych evaluations by Dr Shrink-Rom (Tilda Swinton), and Matt Damon as Management, the furtive face behind ManCom.

An introspective and often amusing misadventure, this is a surrealist miscellany that makes the viewer do the math, and trust us, it adds up to be far greater than zero.

1. Seconds (1966)

This paranoia-addled sci-fi mindfuck from John Frankenheimer is an unforgettably bleak “what if?” misadventure led by a bold performance from Rock Hudson. Frankenheimer’s sinister scenario reads like a gloriously twisted Twilight Zone episode that never was, concerning a milquetoast middle-aged banker named Arthur Hamilton (John Rudolph) who leads a rather sedate suburban life and then decides to undergo a strange procedure offered by a shady secret organization known as the “Company”.

Given a new life and a younger visage along with a different alias to match––Antiochus “Tony” Wilson (Hudson)––can a new existence, starting over from scratch in bohemia California be all that easy?

Seconds is a film full of superlatives starting with Saul Bass’ ominous title sequence and consistently held aloft by cinematographer James Wong Howe’s askew, canted, frequently fish-eyed camera angles, eerie tracking shots, fragmented editing, a gloriously disturbing score from Jerry Goldsmith, and a positively chilling sound design from Howard Beals. How did anything this messed up ever get made by a major Hollywood studio in 1966?

Deliriously downbeat but always exciting and generative of chills both subtle and forthright, Seconds completes Frankenheimer’s loosely assembled “paranoia trilogy” after The Manchurian Candidate (1962) and Seven Days in May (1964). And the ending, which shuts tight our frantic and desperate narrative, is as shocking and horrific as they come. Essential viewing.

Author Bio: Shane Scott-Travis is a film critic, screenwriter, comic book author/illustrator and cineaste. Currently residing in Vancouver, Canada, Shane can often be found at the cinema, the dog park, or off in a corner someplace, paraphrasing Groucho Marx. Follow Shane on Twitter @ShaneScottravis.