5. The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928)

If there’s a film that belongs on this list for just one shot alone it’s this one. It’s impossible to overstate the significance of Carl Theodor Dreyer’s revolutionary use of the close-up shot on Maria Falconetti’s heart wrenching performance as Joan of Arc is being put on trial for heresy. Film was still largely being used more theatrically, keeping the camera pulled back as the actors did their job from a faraway distance.

This film obviously didn’t invent the close-up, it had been used before in other films as experimental playbooks. But it had never been used to this kind of effect, paired up with a performance so genuine and authentic that it breaks the hearts of those who watch it because we become so intimate in our relationship with the character.

Roger Ebert often said that films are the greatest source of empathy in the world because more than any other art form they put us in the perspective of other people. This film, better than any other, personifies this as to this day, nearly 100 years later, there is no film that showcases film’s ability to convey feeling and emotion more than this.

4. 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)

I don’t know if there was a greater visual strategist is film history than Stanley Kubrick. The old story that’s thrown around is that Kubrick would rip out 100 pages of the script and say “we’re going to tell all of this visually”. I doubt this story has any merit but it’s more of a funny way to try and explain his style. “2001: A Space Odyssey” does nothing less than imagine, fulfilling a vision that’s beyond the ramifications of human kind.

The film is told largely through metaphor and there’s really no better way to do it. It starts out in the dawn of man, we see natural images and shapes like water, trees, rocks, dirt, and animals. So to suddenly impose a large, black monolith with its perfect straight lines and edges jars us and brings us to the realization that something else is at work.

The monolith bares a specific resemblance to the Kaaba, the most sacred site in all of Islam. It houses the Black Stone, which in faith was sent down to earth by God to Adam and Eve to advance life on earth. In essence that’s what the monolith is, a powerful object sent by extraterrestrial beings to evolve human life. The film is composed largely of emptiness, long shots that stretch across time.

This is a film made by someone so confident in its craft that it never has a shot simply to draw our attention but rather lets it drift and leaves the rest to us. Space is much like earth when it was young, it was a beautiful wasteland that was left as a void. But through life and development we bring the music and the stars will converge and dance, just like our ships that move in a ballet like motion with one another. This is a masterwork.

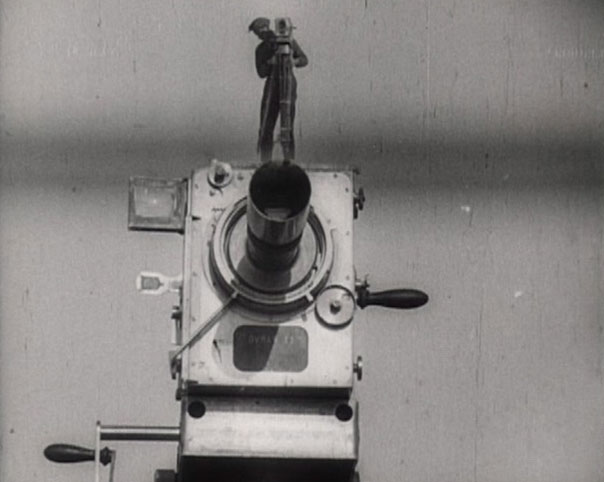

3. Man With a Movie Camera (1929)

When “Man With a Movie Camera” was released in 1929, and for many years after, films had an ASL (Average Shot Length) of 11.2 seconds. This film has an ASL of 2.3 seconds. So obviously it goes without saying that there was absolutely nothing like this at the time and for a long time afterwards. The point that director, Dziga Vertof, was making was to expand what cinema was capable of doing.

At this time film was still in its infancy, relying on the traditional methods of theater and stage. But Vertof knew this had much larger possibilities than what classical theater had. He knew that film could move and process in a way theater never could because everything you see on a stage is happening in real time. But film, now that can be something else entirely.

So the idea was set; he would show 24 hours of a single day in Russian life, take 4 years to film this one day, compose together 1,775 separate shots for which his wife, Yelizaveta Svilova, would edit together. The result is a mesmerizing piece of cinema that pushes the boundaries of what the human eye could process.

2. Citizen Kane (1941)

True story, I was in film school for roughly 3 weeks before I transferred elsewhere to study media at a University and in that short amount of time I watched “Citizen Kane” in 3 different classes. For anyone who’s been a film student like myself you’ve probably had this film shoved down your throat. But there’s good reason for this.

A lot of what we regard as common place in films today is largely due to what Orson Welles perfected in this monumental achievement. If you were to show this film to someone now the gut response will likely be “what’s the big deal?” But that reaction is actually what makes Welles’ film so important, it’s become so common place that we don’t even realize that there was a time when this first had to be invented.

Not that Welles was the first person to do a lot of what you ultimately see in here, but he was the first to string it along in such a way that created what we generally regard as ‘cinematic’. Obviously I’m being vague here, and intentionally so, there’s not much I can add to this that hasn’t already been analyzed to death. But needless to say Orson Welles redefined what the cinematic art form was capable of.

There’s a lot of great things to discuss when talking about “Citizen Kane”, many of which I can’t condense into this short explanation right now. But much like Charles Foster Kane himself, no one word can sum up this film. Not even the word ‘greatest’.

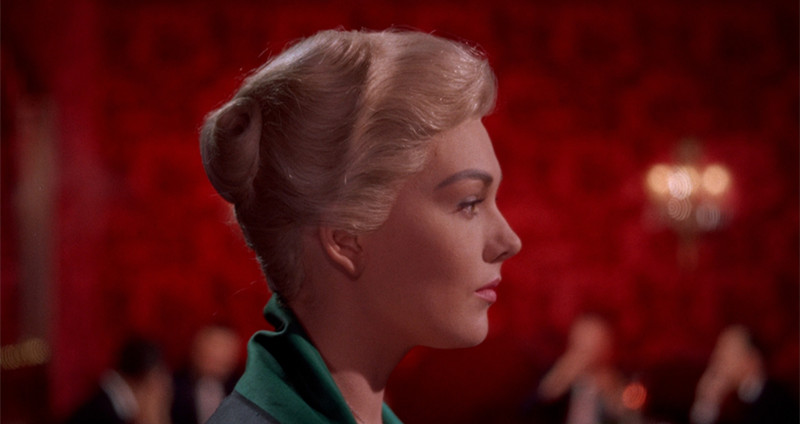

1. Vertigo (1958)

I’ve said in other articles I’ve written how Alfred Hitchcock is perhaps the greatest emotional strategist in film history. There’s never been a director who understands the psychology behind his audience more than he did. With “Vertigo” he made, arguably, his greatest achievement on every conceivable level. William Friedkin once said “don’t waste your time at film school, just go see Alfred Hitchcock’s movies. You’ll learn the techniques now it’s just a matter of finding your own voice, it’s what I did.” I

f there’s any film in Hitchcock’s repertoire that best personifies his ability as a filmmaker it would be this one. This was a film being made by a Hollywood elite, but working outside of the norm that was comfortable for most at that time period. It tells a macabre story of obsession, guilt, manipulation, control, and the other worldly that many weren’t suited with at the time. But Hitchcock knew how to reinforce the film’s subversive power through very key cinematic details.

A common motif throughout the film is the feeling of falling down, this is brought on by Scottie’s fears of acrophobia but in a deeper sense is because of his down turn; how he’s falling in love but is also falling out of reality.

Hitchcock creates a downward motion at numerous points in the film using very precise movement and camera placement. Such as when Scottie is following Madeline in his car and almost every time the camera goes into a POV shot looking forward at Madeline’s car it’s when they’re driving downhill. And notice the way Scottie literally falls in love with Madeline when he rescues her from drowning.

Hitchcock likewise uses color to its greatest subliminal effect here. Reds are linked with Scottie and Greens are linked with Madeline. Red standing for love, lust, caution, and death. Green standing for life, envy, and the ghostly. When Scottie first sees Madeline she’s wearing a beautiful green dress, which stands out in the red decoration of the restaurant they’re in.

Later on when after she’s dead and he meets Judy she likewise is wearing a green dress, linking Judy and Madeline together. There’s a moment where a tree is referred to as ‘always green’, in other words ever living. Madeline is linked with trees as strong, even when she’s physically gone she’s still ever living. But Madeline’s true self is Judy, linked to flowers, not strong and ever living but rather fragile and delicate.

This gives way to another frequent theme, identity. A motif used in the film to show this is ‘the spiral’. The spiral appears at numerous points to show us a twisted nature, a fragmented identity. Scottie has a fragmented identity in which he goes by a number of different names throughout the film. Judy, an actress hired to play Madeline, assumes the role of being possessed by Carlotta, a dead women, and as such fragments her identity through various layers.

At the time “Vertigo” failed to gain recognition because of how ahead of its time it was, but over the years has earned the reputation it deserves. It’s now regarded as “The Greatest Film of All Time” by the 2012 Sight and Sound Critic’s Poll and once you dissect its cinematic language you’ll see why.