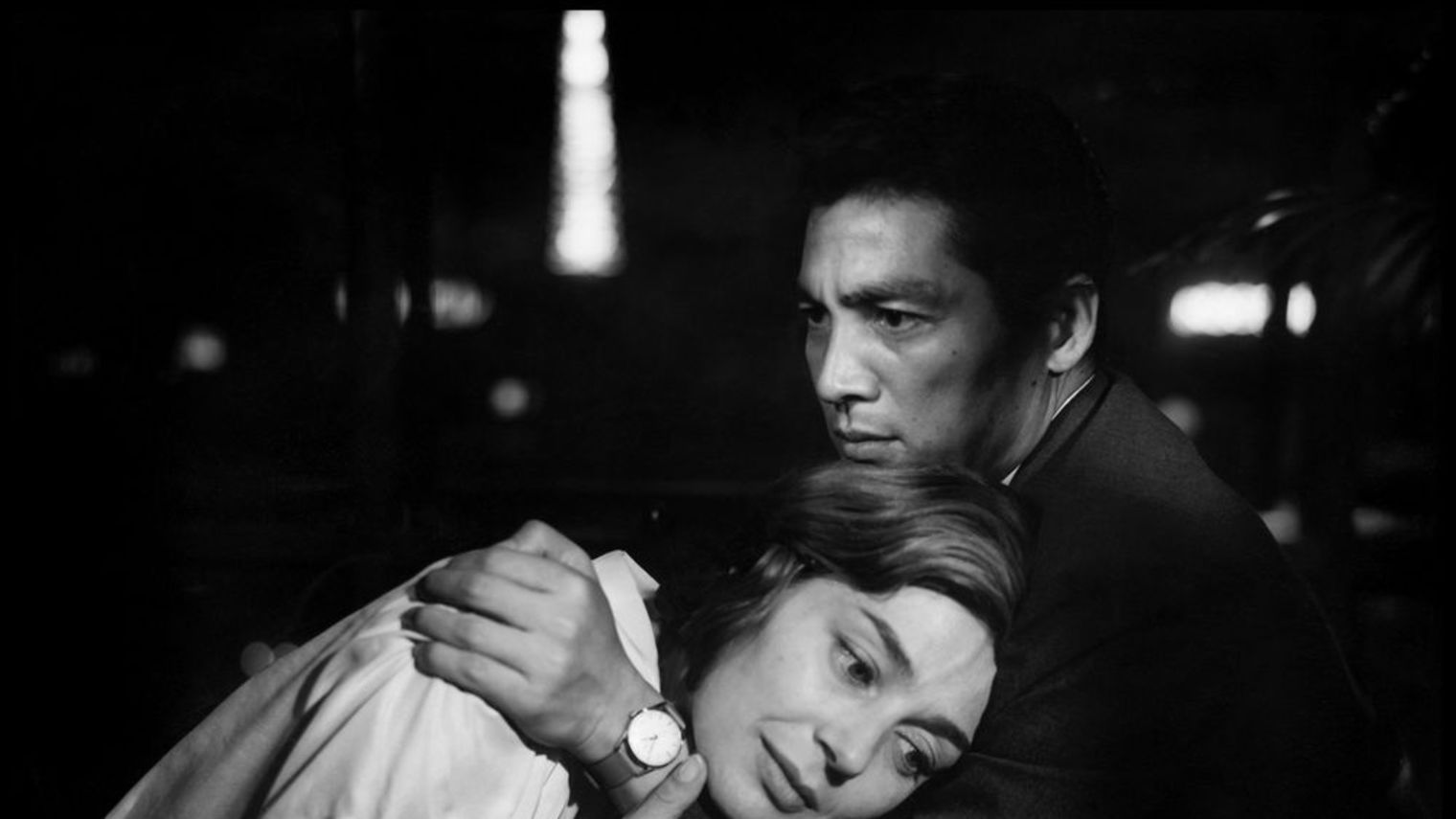

6. Hiroshima, mon amour (Alain Resnais, 1959)

Known as an extreme symbol of the French New Wave, Alain Resnais is definitely a cineast who challenges the viewer. In his masterpiece, “Hiroshima, mon amour,” the director presents similar characteristics to the ones explored in all of his filmography. Resnais makes the viewer feel uneasy, using a cinematographic language that leaves them to question time and space in the narrative, leading to a detachment regarding the plot.

“Hiroshima, mon amour” tells the story of a young French woman sent to Hiroshima to make a film about peace. There, she finds herself passionately in love with a Japanese man who reminds her of her first lover: a German soldier from World War II.

Between pain, love, and her most arduous memories, the woman ends up being martyred and remembering the painful moments of her short existence. Still, losing her lucidity, she believes she was present during the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Arguably one of the greatest geniuses in the history of cinema, Resnais builds in his 1959 work a labyrinthic narrative based on individual and collective memory. Constructed from an unclear timeline – transiting between the 1940s and 1950s – and mentally uninspiring characters, the film is definitely a puzzle.

Its montage, poetic and disruptive, helps in the complexity of the narrative. “Hiroshima, mon amour” is a film that narrates through the confusion and disorientation, challenging the viewer until the last minute.

7. La Jetée (Chris Marker, 1962)

Another revolutionary of the French Nouvelle Vague, Chris Marker is a great exponent of the most radical strand of the French movement. Declared fan of Akira Kurosawa – see his documentary “A.K.” – Marker is a pupil of Jean-Paul Sartre and his classes in the faculty of philosophy.

Aside from being a filmmaker, he was a writer, always exploring his philosophical side. Very close to Agnes Varda and Alain Resnais, Marker was seen by Resnais as a prototype of the man of the 21st century.

“La Jetée” is set in a dystopian world, post-World War III. There, a prisoner is used as a guinea pig for time travel experiments that are capable of saving mankind. He is sent to a time before the war, to a pier, where he remembers having seen a beautiful woman. They then develop a loving relationship, which causes the man to give up his present and confront a dim memory.

The raw material of cinema is certainly the image. More precisely, the static image, the photograph. Movies are just a series of frozen images that produce the sensation of movement. In “La Jetée,” Marker returns to this base of the seventh art and produces one of the most impactful films ever made.

Filmed only with photographs, the narrative of the film is conducted through narration, transforming the image into an aesthetic resource. This is closer to literature, where words count, and our minds create iconographic references to what is read (or heard).

8. Otto e mezzo (Federico Fellini, 1963)

Federico Fellini and Marcello Mastroianni in the purest artistic harmony. The Italian genius synthesized in “Otto e mezzo” all of his cinematographic aplomb, reaching the apex of his art. The two have had numerous partnerships in cinema, including “La Dolce Vita,” the director’s most famous film. Remembered for his irreverent aesthetic – fantastic, sometimes comical and critical – Fellini is a striking figure in the collective unconscious of Italy. Still, he served as inspiration for masters such as Stanley Kubrick, David Cronenberg, and Martin Scorsese.

“Otto e mezzo” is, according to reports, an autobiographical film. In it, Guido, a filmmaker in crisis, desperately seeks some source of inspiration. Through dreams and fantasies, Guido is at such a point of mental confusion that he can no longer distinguish reality from illusion. Isolating himself in a place of waters, the filmmaker rests and, through his dreams, begins to develop his creativity.

There are metalinguistic films that deal with directors and the difficulties of creating works. There are also films that explore the human psyche in a unique way. Putting together these different ideas, there is “Otto e mezzo.” Fellini enters the branch of Jungian psychology and creates a work that exposes the great crises and anguish of a film director.

Fleeing from the material branch, the problems and psychological challenges of cinematographic making are presented. Filmmakers are not divine beings who have genius inspirations and daydreams at all times – they are humans with doubts and anguishes, just like any human being. This is what “Otto e mezzo” approaches, in a critical and comical way.

9. Scenes from the Life of Andy Warhol: Relationships and Friendships (Jonas Mekas, 1990)

Returning to the current creation and idealized by Maya Deren in the 1940s, here is Jonas Mekas. This Lithuanian-American director is considered one of the most important names of avant-garde cinema in the United States.

There, he ended up getting close to iconic American underground figures, such as Andy Warhol, John Lennon, Allen Ginsberg, and Yoko Ono. In the field of experimental cinema, Mekas had as a personal friend the filmmaker Stan Brakhage. In his native country, he is known for his texts, both in prose and in poetry.

As the title itself says, “Scenes from the Life of Andy Warhol” is an odd movie about the life of legendary pop artist Andy Warhol. Amongst several passages in the old Factory, Mekas documented shows in which Warhol participated, encounters with mythical figures from the 1960s, and finally, a peaceful daily life, the complete opposite of the bohemian life of drugs and narcotics.

As usual, Mekas does not make a simple film, documenting such scenes in a classic way. Filled with experimentation, “Scenes from the Life of Andy Warhol” is a more advanced experiment of a representation of the human memory in the cinema.

In this, completely disconnected scenes are recorded by remains of films and edited in a non-narrative way, with no pretension to follow a narrative. In addition, the soundtrack that does not stop at any moment is a striking feature of this masterpiece of experimental cinema.

10. Stellar (Stan Brakhage, 1993)

If Maya Deren and Jonas Mekas deconstructed, Stan Brakhage abstracted. Another American component of the group of experimental filmmakers, Brakhage was also a writer, having published the book “Metaphors of Vision,” in which he exposes his innermost thoughts about the image. His main films had no market bias and were usually displayed in galleries of modern art. Like Mekas, it was very close to the underground scene in the United States.

In “Stellar,” the filmmaker goes back to the maximum origins of his film abstraction. In three minutes, Brakhage designs on canvas several abstract paintings – reminiscent of Jackson Pollock – that literally create a stellar setting. Throughout the duration of the film, various stimuli are fired at the viewer to make them feel ecstatic with such beauty. Here, there is no story, no narrative; it is the search for a unique vision and the exploration of cinematographic materiality.

Brakhage definitely gives up trying to tell stories in his films; he prefers the search for odd stimulation. Thus, he presses for the experience of seeing completely abstract images passing in front of the viewer’s eyes.