From the time the Lumière brothers started experimenting at capturing and storing everyday realities in moving frames to the cinema of the 21st century, we have traveled through decades of advancement. This had been made possible by early pioneers who realized the potential of cinema at such a time, and with careful observation and experimentation, invented new features and techniques that enriched the cinematic eye.

If we try to contrast today’s advanced cinematic techniques with the creative outputs of previous decades, it may seem dated and hyped, but without those initial inventions, we wouldn’t have gone anywhere. They literally created magic with their creativity with such limited resources, and this article wants to celebrate those achievements.

Though there were several brave people who tried their hand at experimenting with the early forms of the cinematograph, for the sake of brevity some of them have excused here. Instead, we have listed those visionary film works that helped cinema to leap unprecedented heights instantaneously with their quality.

The Lumière brothers are also excused here because apart from commercializing the initial short films, they underestimated the potential of cinema with the statement, “The cinema is an invention without any future.” Filmmaker or not, these works are necessary viewing for every film lover. Watch these marvels and astound with their amazing qualities. Without further ado, here are 25 classic films that are cornerstones of cinema.

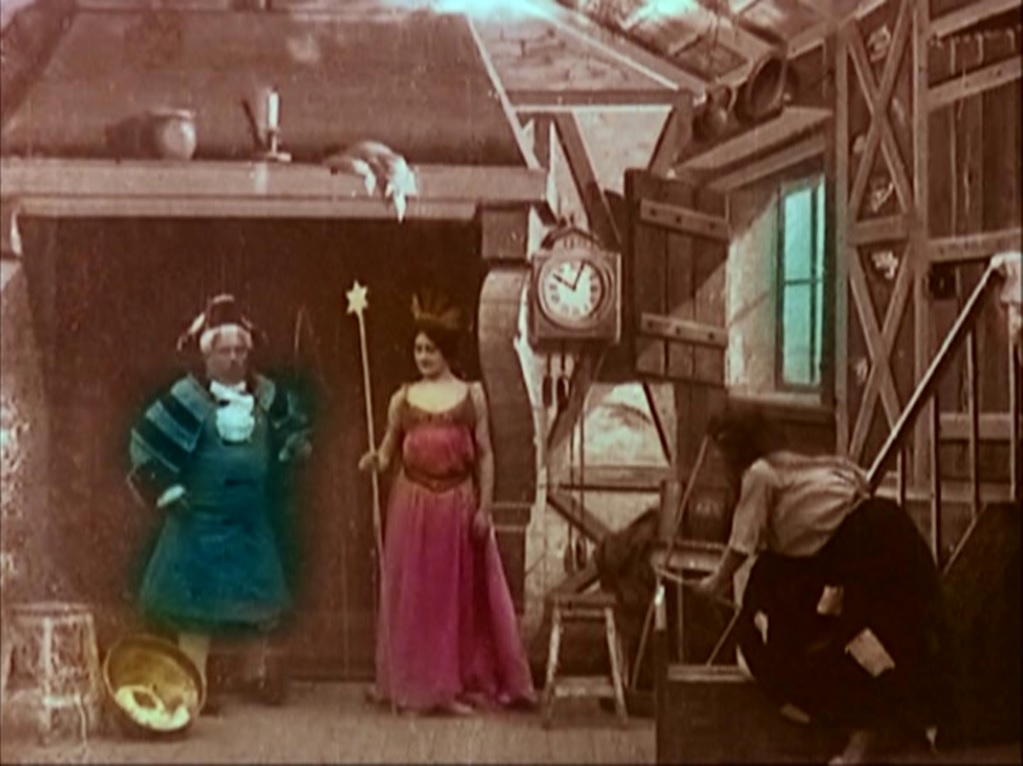

1. Cinderella (1899) Directed by: George Méliès

For the most attentive and scholarly film viewers, George Méliès’ crowning achievement is “A Trip to the Moon.” It was a legendary piece of work for sure, but cinematic magician Melies first started polishing the cinematic future with the first film adaptation “Cinderella.”

In the small runtime of five minutes and 38 seconds, Méliès presented a coherent plot and used the first transition dissolve, which shaped the editing style of the future. This was also the first time multiple scenes were included in a film. With fantastic set design and assured direction by Méliès, it is a treat for film lovers.

2. A Trip to the Moon (1902) Directed by: George Méliès

This is the film for which Méliès is frequently labeled as the original cinematic magician. Apart from holding the record of filming the fastest science fiction film, Méliès employed all of his invented techniques in his “A Trip to the Moon.”

Here, for the first time in the history of cinema, he used special effects for which every sci-fi film owes to him. He made use of all the scarce goodies from his bag including stop-motion and superimposition. It also used a hand-painted backdrop, multiple exposure, and nonlinear editing to create the finest fantasy film of the earlier times.

3. The Great Train Robbery (1903) Directed by: Edwin S. Porter

With “The Great Train Robbery,” Edwin Porter shot us at gunpoint. The image of the bandit shooting directly toward the camera is a frame for the legend books. Just like in the Lumière brothers’ projection, the arrival of a train terrified early viewers; this shot was another one of the greatest scary moments in cinema at a time when the violence is now prominent, in your face, not in subtle hiding.

Expanding on the work of “Life of an American Fireman,” Porter used composite editing, cross cuts, and real location shooting in this film. He first showed that cinema can manipulate time by presenting two different viewpoints of the same time, to which our editors owe so much.

4. The Birth of a Nation (1915) Directed by: D.W. Griffith

What the experimenters before D.W Griffith tried to do with new established editing patterns, Griffith exemplified them in this project. Lately, this film has created controversy for its pro-Ku Klux Klan sentiment, but regarding the technical mastery, Griffith is at his best here.

“The Birth of a Nation” had used continuity editing techniques at their best advantage with the master filmmaker frequently changing the distance of the camera from the subject seamlessly. For the first time, the tempo and the pace of the film are also manipulated with absolute precision according to the climatic needs of the story.

The parallel editing doesn’t seem jarring, with special attention given to the establishing and close-up shots. For heightening the melodrama and sentiment of a certain scene, he showed a single scene numerous times for a significant length, but the outcome was no less exemplary.

5. Intolerance (1916) Directed by: D.W.Griffith

The invention of thematic juxtaposition started with “Intolerance.” Here, the ambition was high with Griffith presenting the story of four different decades woven in a single film, and he succeeded magnificently. He tinted each decade with different colors and cross-cut back and forth between sequences.

Humanity’s bigotry and cruelty was never more appalling with Griffith increasing the tempo of the cross-cutting by decreasing the time of the segments to reach a horrific final climax.

6. The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920) Directed by: Robert Wiene

The poster child of German expressionism, “The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari” continues to teach modern filmmakers how to effectively make a horror film with scarce resources, such is its legacy. The early pioneers had nothing but the creative urge within them and they realized that they can only scare the audience with transferring the film’s atmosphere to an unrealistic plane.

So they framed the scenes angularly, invertedly with weird geometrical shapes, and created a terrifying atmosphere with expressionistic set design and art direction. The result is a surreal, weird creepy film that is material of a nightmare.

7. Ballet Mécanique (1924) Directed by: Dudley Murphy and Fernand Leger

Dudley Murphy and Fernand Leger realized the absurdism inherent in the relationship between mechanics and art and made this film. Every film of the earlier generation was an experiment in itself, but this was the first avant-garde film that was conscious in exhibiting what it wanted to convey.

Non-animate and animate things perfectly synchronize in the film to create an intentional psychological jarring effect. With George Méliès, cinema discovered the future of surreality, but Murphy and Leger contributed more with this single absurdist postmodern dadaist flick that paved the way for today’s brave experimental filmmakers.

8. Mother (1926) Directed by: Vsevolod Pudovkin

The early Russian filmmakers knew the inherent power hidden in the sequencing of the images, that in an individualistic sense, they are powerless, but when in the hands of a proper filmmaker, their idealistic and thematic synthesis trumps over. More fluid and poetic than his counterpart Eisenstein, Pudovkin built his “Mother” as a more personal story where the editing follows the rhythm of psychological progression, not the rule of creating maximum shock.

When a prisoner received the letter of his end term, after a close-up of his shaken hands, Pudovkin showed the shots of the brook, a play of sunlight in the pond, and the laugh of a child to sympathize the audience with the prisoner’s emotion. Film editing finally becomes a highly decorative and utility item with the hand of Pudovkin.