5. Alfred Hitchcock & Robert Burks

Alfred Hitchcock used to play with Hollywood’s rules (begrudgingly, of course). There was a time he began to get fed up with the studio system’s influence on films, especially since they were considerably stronger than the impact that a director had (this was likely around his feuding with David O. Selznick and the filmmaking of Rebecca). Once he went his own way and became a rulebreaker, certain partnerships started.

One major example is with cinematographer Robert Burks (one of the all time greats). He helped Hitchcock with his sinisterly lit black and white films, and he also ushered in his colourful pieces, too. He did not just have a good eye, he had an imaginative eye.

The fixed perspective in Rear Window. The use of the camera as a special-effects creator in The Birds (particularly with making the birds look real). Hitchcock’s crazy visions needed to work their way into your head, but Burks was the key into the portal of your mind; he was mean enough to grant Hitchcock that access.

4. Andrei Tarkovsky & Vadim Yusov

When it comes to the grande epics of Andrei Tarkovsky, you will find some of the best cinematographers out there (Sven Nykvist being one example, who will be brought up later). The strongest case is Vadim Yusov for a number of reasons. Firstly, Yusov worked on the majority of Tarkovsky’s works (from Ivan’s Childhood until Solaris). Secondly, these films are gorgeous visually.

Sure, Mirror and Sacrifice aren’t included here (nor is the brooding Stalker), but we have Andrei Rublev, which is so damn well shot that it still feels ahead of our time (let alone its own time). Tarkovsky was obsessed with symbolically pleasant images, both the kind found in nature and those within our imagination.

Yusov made it work, ranging from obscure reflections, to the most precise mise-en-scéne. That came to play in the faith-bolstered Anrei Rublev, and the nature-vs.-technology contrasting found in Solaris (where trees create a perfect harmony, and structures are humanity’s own art forms).

3. Wong Kar-Wai & Christopher Doyle

We have reached a point in cinema that the famed Hong Kong director Wong Kar-Wai’s works are being referenced in many instances. Kar-Wai has a knack for reinventing what poetic cinema feels like, and much of that comes from the fever dream he creates.

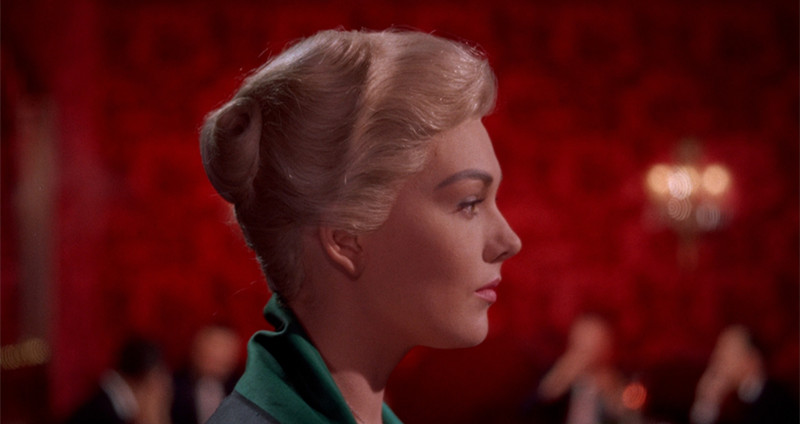

A huge portion of this haze is due to the viciously lush colours that quench a cinematic expectation that many art house enthusiasts crave. Christopher Doyle’s use of gel colours allows these scenes to be absolutely drenched in whatever hue is being bestowed upon them. We have the richest of greens, the deepest of reds, and the brightest of yellows.

Calling these films monochromatic does not even begin to cover what they look like. Lighting begins to leak into the organic elements of a scene, as if neon and flesh are one. Kar-Wai’s themes of an environment encompassing its subjects is brought to life with Doyle’s obsession with drowning-out every scene.

2. Ingmar Bergman & Sven Nykvist

Like Hitchcock, Ingmar Bergman slowly got more and more frustrated with the limitations of the studio system. His works got more and more inventive as he tried to push away from conventionality. During this transition, he began working with Sven Nykvist on Sawdust and Tinsel: a film with some insanely underrated shots, particularly the use of reflections in water and mirrors.

Nykvist started bringing Bergman’s dark visions to life, whether it was death incarnated or the nightmares of the nearly departed. His use of black and white was astounding in its own right. Then Bergman finally moved to colour based films, and Nykvist’s imagination went wild.

He kept Bergman’s fascination with tonal simplicity and made it a necessity. Cries and Whispers’ uses of black, white and red is a fine example of this powerful use of basic colours. When it came to Bergman’s artistry, no one brought it out better than Nykvist.

1. Stanley Kubrick & John Alcott

This pairing is the number one slot on this list, despite how brief it is. Stanley Kubrick and John Alcott only worked on four films together. However, each of these four films tells its own story. Kubrick was obviously a renowned photographer before he became a filmmaker. That’s where much of his perfectionism behind the looks of his films came from.

We wanted to make images of dread in The Shinging. Alcott allowed for the coldest blues, blankest whites, and bloodiest reds to resonate in each respective scene. Kubrick wished for chaotic order in A Clockwork Orange. Alcott abided with symmetrical shots colliding with experimental lenses and extreme close ups in other shots. We reach the two key examples of why this entry is the greatest of all time.

First, we have Barry Lyndon, where special cameras were invented to utilize natural lighting. The entire film is a moving painting, whether it is full of pastel colours or the burnt ambers of candlelit subjects.

Second, there is 2001: A Space Odyssey, where Alcott’s breathtaking cinematography opens the film during the Dawn of Man portions (Geoffrey Unsworth shot the rest of the film beforehand). Whether Alcott was working on Kubrick’s visions from the start, or finishing projects that were left incomplete, Alcott always kept up with Kubrick against all odds. This is why this is the best director-cinematographer pairing of all time.