When the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences was founded in 1928, its primary goal was to add a bit of prestige and luster to the motion picture business….the Hollywood movie business.

While it is, of course, certain that those creating the organization knew that there was a world of film making outside of Hollywood (especially since so very many of the members and others in Hollywood originally came from some of those places), the Academy wasn’t too concerned about what went on outside of their strictly boundaried little world.

While a film from somewhere other than Hollywood could conceivably be nominated or win one of the Academy’s annual prizes, it was highly doubtful that it would happen.

When the French classic A Nous la Liberte was nominated for its set design in 1932, it came as a big shock, as did Charles Laughton’s best actor win for the 1933 British Film The Private Lives of Henry VIII (though the fact that Laughton had been working in Hollywood for two years by that time did take the curse off a bit).

As far as the top prize, best picture, goes only French director Jean Renior’s timeless classic Le Grande Illusion (1938) rated even a nomination (it was an off year in Hollywood and the French film towered over everything and still lost).

After World War II the Academy, thanks to the increased awareness of other countries fostered by the conflict, started giving out honorary awards to foreign language films considered worthy (with Italy’s Shoeshine and Bicycle Thieves, France’s Forbidden Games, and Japan’s Rashomon and Gate of Hell being among the recipients). This lasted from 1947 to 1955 and there was no competition for this award, which was given out solely at the Academy’s choosing.

Starting in 1956, best foreign language film became a real award category. This category has always generated much controversy since a myriad of rules govern it and voting for this award is only allowed if Academy members meet certain strict guidelines (though there are other categories, such as short subjects, which have similar rules).

One important thing to remember in looking over the list of what the Academy did and didn’t award or even nominate: the films selected for the category were submitted by the country of origin.

For example, Spain engendered much controversy when it refused to submit film maker Pedro Almodovar’s much acclaimed 2002 film Talk to Her, reasoning that, after his win in 1999 with All About My Mother, Almodovar had been lauded enough (and there are and were past histories of film makers winning multiple times in this category).

The end result was that that Spain’s official entry, Afternoons in the Sun, was not among the nominated but the Academy used its prerogative to nominate Talk to Her in other categories, non-specific to foreign language films, and Almodovar ended up winning for his screenplay. (Though, to date, Spain has never submitted another Almodovar film for consideration as best foreign language film.)

In considering the following list, be mindful that it concerns only the films winning or nominated for the award. It would be nice (and quite accepted) to say that Ingmar Bergman’s The Seventh Seal and Wild Strawberries (both 1957) or Francosis Truffaut’s The 400 Blows (1959) or Jules and Jim (1960), for example, should be among the award winners but, in these cases, Sweden and France didn’t agree at the time. Here then is a list of some interesting winners and some interesting conflicts within this Oscar category.

1. Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow (The Umbrellas of Cherborg, The Woman in the Dunes) – 1964

It’s a pity that the Academy didn’t get its act together in regards to foreign films much sooner than it did for more than one reason. If there had been earlier recognition of work from places outside of Hollywood, then such artists as Rene Clair, G.W. Pabst, and Jean Renior might now be listed among those honored by the Academy (or, knowing the Academy, maybe not….).

One artist who wasn’t able to compete in his prime years was Italy’s Vittorio De Sica, who had a long career both before and behind the camera but who will forever be remembered as one of the principal movers of the famed Neo-Realist movement in Italian cinema.

Though he was given honorary awards for his finest works, Shoeshine in 1947 and the unforgettable Bicycle Thieves in 1949, the Academy seemed to feel some strange sort of guilt towards him (as will be explained even more fully later in this article).

In 1957 he received one of the least deserving acting nominations ever for his supporting turn in the big Hollywood dud A Farewell to Arms. Then came 1964 and his award for Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow.

First, let it be stated that this is not at all a bad film. Its a very pleasant three part omnibus of comedic love stories, all starring Italy’s leading stars (and favorite cinematic romantic couple) Marcello Mastroianni and Sophia Loren (and though Mastroianni worked with many great European film makers, De Sica was truly Loren’s special director).

Though one might detect some of the film maker’s Neo-Realist roots in the lower and working class backgrounds of the stories (especially the third, which casts Loren as a friendly prostitute), this could not be farther from the films which made De Sica’s reputation. In fact, its really rather fluffy, which perhaps accounts for the fact that, for a foreign release, it was surprisingly popular at the box office. OK, it has a good pedigree and was a hit. Sadly, it was not the best.

Among the other films nominated that year was another romantic film was was also a big hit and has weathered the years even better. Many, to this day, count French film maker Jacques Demy’s somewhat tragic but colorful and lovely film operetta The Umbrellas of Cherbourg to be among the screen great romances.

Demy was truly a special film maker in that he could make ultra-romantic, dream-like, and almost fairy-tale (and in some cases, no almost) plausible within his cinematic realm for the course of a few hours and imprint them deeply in the memories of audiences who could give themselves over to his vision. (In Umbrellas case, he was greatly helped by a very young Catherine Deneuve and Nino Castlenuovo and the late and great composer Michel Legrand, who received three nominations for his work.)

Umbrellas was also nominated in three other categories, including one for Demy’s screenplay. There was also another romance, of sorts, among the nominees and no sentiment was involved in that one.

Japanese filmmaker Hiroshi Teshigahara’s The Woman in the Dunes (taken from noted Japanese writer Kobo Abe’s acclaimed novel) is still a most highly regarded film (and Teshigahara also received an individual nomination for his work).

It might well be that the two distinguished films left the field open for a dark horse (and the other nominees, Raven’s End, an early work from Sweden’ Bo Widerberg , and Sallah Shabati, a now forgotten film which was the first to be nominated from Israel, didn’t have much spark). The Academy has done worse than honoring a world class film maker, but it could have done better.

2. A Man and a Woman (The Battle of Algiers, The Loves of a Blonde) – 1966

Perhaps romance is the universal language for two years after Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow won, history truly repeated itself in this category.

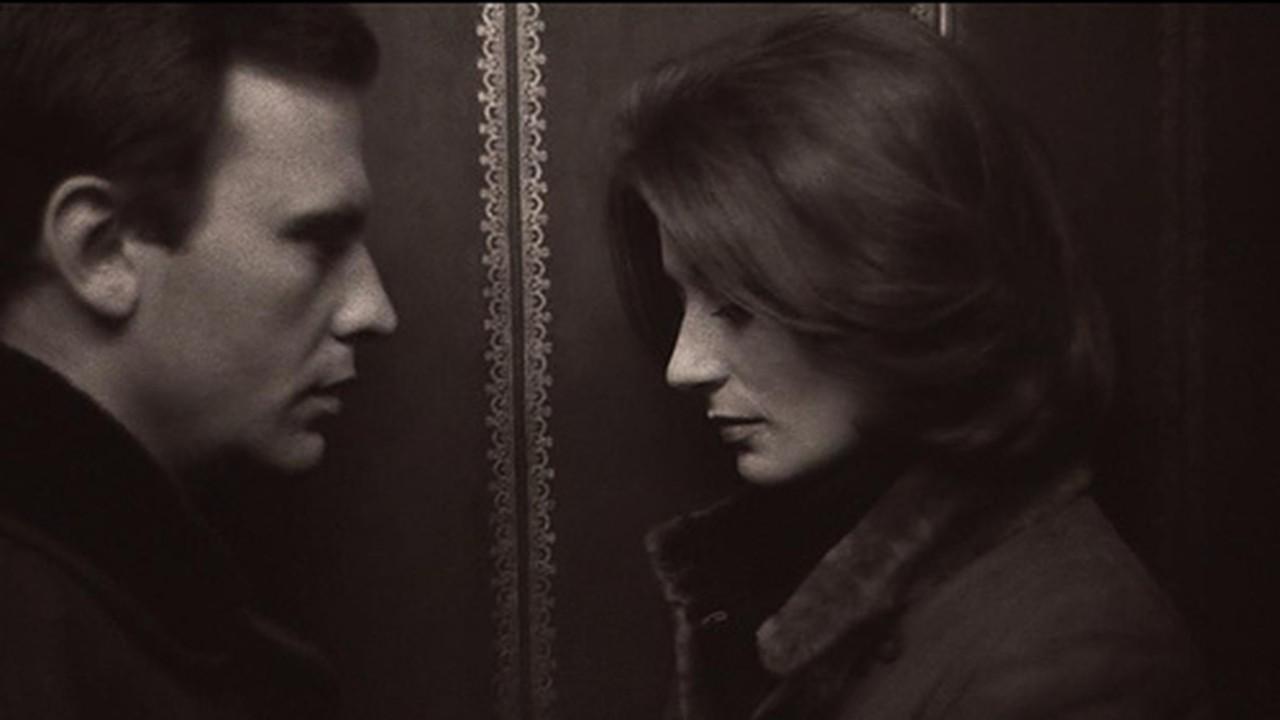

Any lover of romantic films with a knowledge of world cinema surely knows A Man and Woman. This was the supreme effort of the well-remembered French film maker Claude Lelouch.

Its story was simple enough to write on the back of a napkin: a lovely young widow (Anouk Aimee, nominated for best actress for a good performance in one of Hollywood’s worst years for actresses) meets a handsome young widower (that icon of French cinema Jean-Louis Trintignant) at the boarding school their children attend. She can’t forget her late and beloved stuntman husband but the man is a famed race car driver!

Can she commit? Well, it must be stated that it took some real work by some excellent people to get this plot and characters taken seriously (though the greatest of all was composer Francis Lai and his memorable theme music, causing him to be imported to Hollywood four years later to Oscar winning effect for Love Story, a film which shows just how much really good work went into making this one watchable).

This was also a favorite in the film community since Lelouch had to scratch up the money for it any way he could (which is why the film keeps switching from monochrome to color) and the actors worked for a potential cut of the profits. That story is actually more compelling than the one on the screen.

A Man and a Woman’s win might not seem all that bad except that there were other, more deserving, films up against it. That year Eastern Europe was alive with cinematic (and political) potential which would be sadly snuffed out shortly thereafter.

There were nominees from Poland (Pharaoh), the country which was then Yugoslavia (Three) and, best of all, the then-country of Czechoslovakia with The Loves of a Blonde, the breakthrough film of perhaps that country’s great film maker, Milos Forman (who would later come to Hollywood and climb to the Oscar winning summit).

However, even these nominees and the winner stand in the shadow of the fifth nominee an official entry of Italy, famed political film maker Gillo Pontecorvo’s much lauded semi-documentary The Battle of Algiers. A film of influential style and substance, Battle is studied, watched, and written about to this day. If the Academy had wanted to make a choice for the ages, here it was.

However, politics of all sorts seem to govern foreign made films. A few years later French film maker Marcel Ophuls’ pantheon level The Sorrow and the Pity lost to the dinky pseudo-doc The Helstrom Chronicle and this decision ranks right up there with it in the annals of Academy mistakes. Sometimes how the Academy chooses can be put down to matter of taste. In this case, one is left searching for a reason.

3. The Garden of the Finzi-Continis (Dodes ‘ka-den, The Emmigrants, Tchaikovsky) – 1971

This particular entry may be entitled De Sica make-up award part deux. In all honesty, calling the award given to The Garden of the Finzi-Continis anything but a justified matter of taste is much dicier than taking issue with the one given to Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow.

Taken from a well respected Italian novel, the film tells the story of a very wealthy family of Italian Jews in the late 1930s. The forbidding winds of danger and doom are blowing all around them thanks to Italy’s political union with Germany but the group decides that they will be the ultimate ostriches and live quite happily behind the gated walls of their palatial home with its luxurious gardens with tragic results.

The film is memorable and well made but bears virtually no trace of the gritty style for which De Sica was famous (the story ends just as the ugly part is really about to begin). One might not take issue at all with it, as stated, except that some even more memorable films got short changed.

Putting aside the now forgotten Israeli film The Policeman, the list included the excellent Russian bio-pic Tchaikovsky (which looked much better than British director Ken Russell’s outrageous take on the composer’s life, The Music Lovers, released the same year), a fine entry from no less than Japan’s great film maker Akira Kurosawa, Dodes ‘ka-den, and the one film to break out of the foreign language Academy ghetto, Swedish film maker Jan Troell’s now-classic The Emigrants.

Any of them would have been a worthy winner and a win for Kurosawa, who was going through a truly tough period which hadn’t been relieved by the domestic reception for Dodes ‘ka-den, a tale of life among the poverty stricken of a large city, would have been a great boost. In fact, he was (infamously) nearly driven to suicide by the episode (and the film is far more highly regarded now).

However, The Emigrants is not only a superb film (from a classic Scandanavian novel dealing with 19th century rurals heading for a hoped for new life in the US) but a real triumph for Troell, who directed , wrote and photographed (!) the film.

The next year the story’s always planned second half (not sequel), The New Land, was again nominated in this category (losing, more justifiably, to Luis Bunuel’s The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie). Perhaps if the voters could have seen the two halves together they might have realized what a towering achievement this work was in the end. As it was, Oscar has done worse but missed out on the real prize.