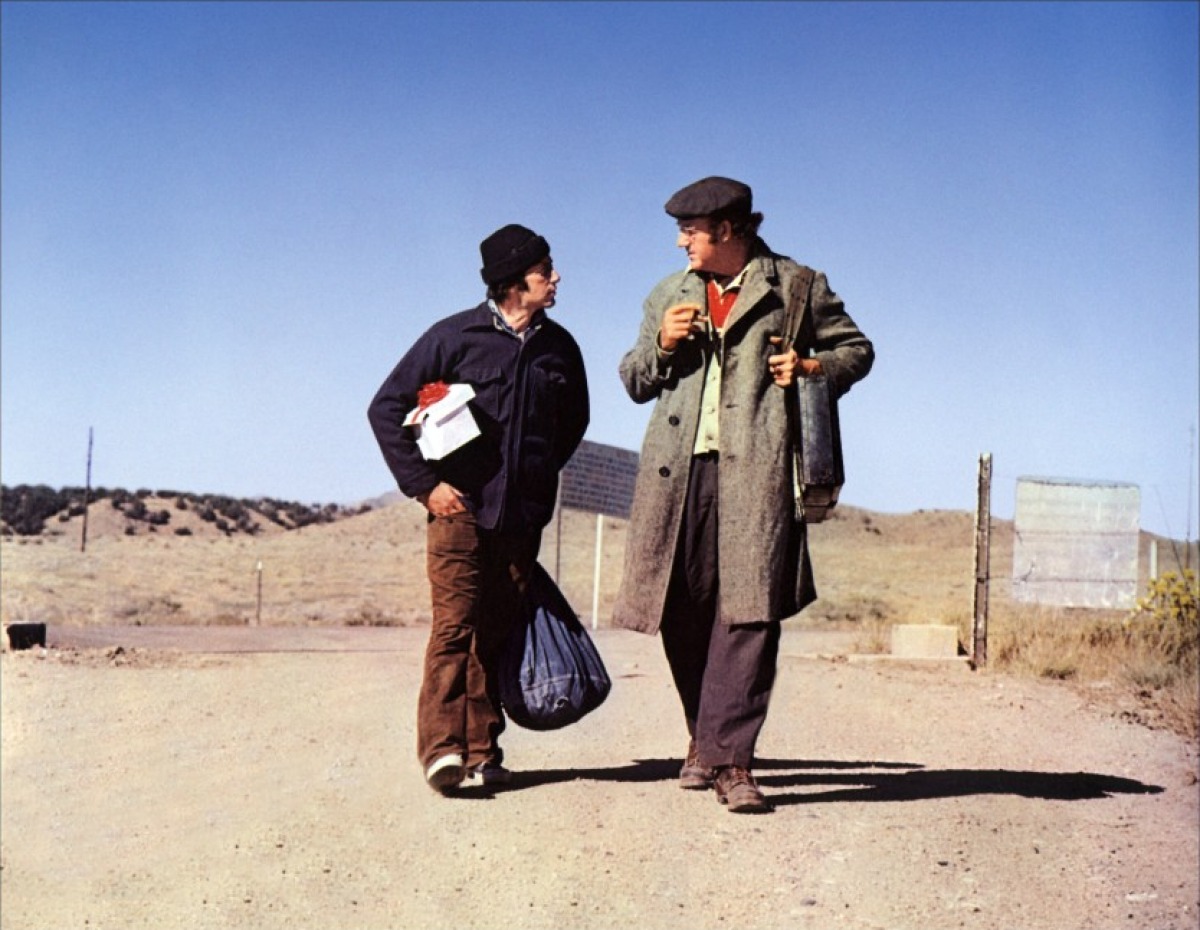

6. Scarecrow (Jerry Schatzberg, 1973)

Sometimes friends literally just drift into one another. Sometimes those friends are such a perfect fit that each one fills the empty space in the other. And, sometimes, seeing that perfect friendship come to an end is like watching hope pass on.

Gene Hackman and Al Pacino play Max and Lion, two drifters who meet and click and spend the rest of the film together rambling towards their respective destinations. Max is eager to go to Pittsburgh to open a car wash and Lion is itching to go to Detroit to meet the young son he’s never seen.

Episodic, rich in character detail, starkly naturalistic one moment and exuberant and silly the next, the different tones of the film mirror the opposing personalities of the two men. And the title functions as a device that is used in the film to delineate those opposing personalities. For hard as nails Max, a scarecrow protects the farmer’s crops by scaring off the crows. But, to amiable Lion, the scarecrow is funny. The crows don’t eat the crops because they appreciate the laugh the farmer has given them.

All these endings leave a mark and this one is no different. It’s quiet. It’s private. It’s sorrowful. It is triggered by a dream ripped away – a dream 5 years in the making that takes five minutes to destroy. The dream is represented by a small white box with a red ribbon on top. It never leaves his side until the dream does.

7. The Elephant Man (David Lynch, 1981)

The last moving moments of this film did not spring from some screenwriter’s wild imagination, but came from the very real life of a man who lived in London in the late 1800s. Though suffused in sorrow, it presents the culmination of that man’s struggle from abused freak show attraction to a cared for and respected gentleman of society.

Somehow, producer Mel Brooks, yes, that Mel Brooks, found a very green David Lynch and said yes to him directing what turned out to be a supremely well acted, low key drama about the life of one John Merrick – a man severely deformed due to his mother being knocked down by an elephant while she was 4 months pregnant with him.

Mean men in a foul mood would freeze in their fury and struggle in vain trying to keep their bottom lip from quivering if they were forced to watch the delicate drip, drip, drip of the last moments of John Hurt, as John Merrick.

Your ears soothed by the rise and fall of Samuel Barber’s “Adagio For Strings”, the camera pans over a cardboard cathedral, cuts to an illustration hanging on the wall, and then, finally, pans over to a bedside photo. These three items have one thing in common for Merrick – each only truly exists in his imagination. This night, though, Merrick will make one a reality.

8. Life Is Beautiful (Roberto Benigni, 1997)

The winning of a child’s game and an escape from an adult horror fuse together to create an ending of such tender comic beauty that even Chaplin, himself, would applaud.

Cinematically venturing into the world of the single greatest abomination of the 20th century with the sensibilities of a classic screen clown is not recommended. Yet, Benigni did just that and pulled off a, yes, hilarious and deeply moving Oscar winning ode to survival in the face of the most dire of circumstances.

After his entire family is captured by the Nazis, and taken to a concentration camp, Guido (Benigni) struggles to shield the horrors of the Holocaust from his young son by making him believe that they are actually playing a child’s game in which the winner receives a toy tank.

A child’s wonder and glee. A mother’s profound relief. The end of one of the most savage conflicts of the modern age. All three of these elements merge into one to form an ending that leaves you simultaneously joyful and wiping away tears.

“We won! We won!” Reunited with his mother, arms raised, shouting out in celebration, the child has no idea just how much of a victory has been achieved. In the end, that is what will get you the most.

9. When We Leave (Feo Aladag, 2010)

Family can be a source of enduring love. But, it can also turn toxic and suffocating and lead to the kind of symbolic and tragic ending that plays out in the streets of an adopted homeland in this searing, note perfect drama.

Abused wife Umay flees, with her son, back into the arms of her family only to be told that she is not welcome and that she must return.

The rot at the root of a cultural code that leaves its’ women at the mercy of the male members of the family leaves the entire tree sick. No one is spared. Women weep at the emotional and physical violence they endure. Men weep at the emotional and physical violence they inflict.

Sometimes you know where you are being taken and yet are still surprised at what you find when you get there. Such is the case here, as director Feo Aladag begins her film with out of context images taken from the end. Due to this remarkable bit of filmic misdirection, the ending, which would otherwise be expected, yet still tragic, surprises you and leaves you even more shaken. And it’s no empty trick – it informs the totality of the narrative.

Dark, tragic and symbolically loaded, the conclusion to the drama that slowly wraps its’ rusted chains around Umay is that of a greater disaster – one that spares no one.

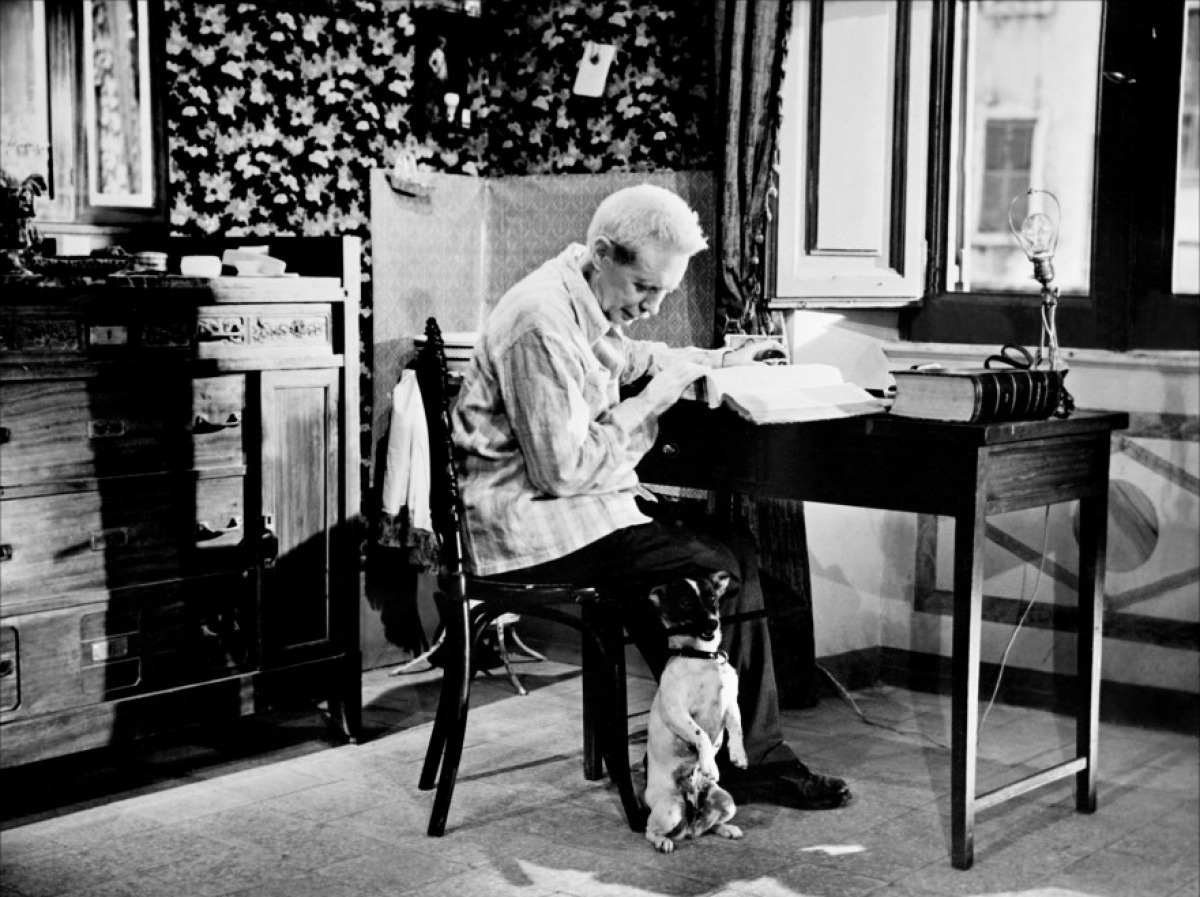

10. Umberto D. (Vittorio De Sica, 1951)

A perfect summer day. Children playing in the park. An old man and his dog. A nearby railroad crossing. The last lingering images of this Neo-realist classic call us over, like a good friend, and putting an arm around our shoulder, shares something fundamental and moving about humanity’s enduring desire for dignity.

Pensioners in post-war Italy are living a threadbare life. Umberto Domenico Ferrari and his small dog, Flike, are living in a small apartment under the iron fist of a landlady who is going to throw them out if Umberto doesn’t pay his back rent.

A dog is a man’s best friend, and sometimes, his only. Ignored and discarded by the government, by his landlady, by his friends, Umberto is on his own, though, not entirely. Flike is his pet, his child, his friend and, ultimately, his joy. They have each other. But, is that enough?

The cracked stone steps that lead down to the final moments of, “Umberto D.”, are taken slowly and carefully by De Sica. Nothing is rushed. He wants you to feel the desperation in the old man. He wants you to feel the contrast between it and the joy of those around him. He wants you to see how he is callously viewed by those around him. He wants you to feel for Flike and feel his helplessness. Finally, De Sica wants you to notice it is a perfectly sunny day. Heartbreak doesn’t need the rain. It just needs the tears.