5. Moon

Duncan Jones’ “Moon” is one of the most provocative and affectionate science fiction movies of the past decade. Characterized by its profound treatment of the human condition, the underhandedness of a dehumanized corporation, and artificial intelligence on the cusp of sentience, “Moon” features a singular performer in Sam Rockwell who plays Sam Bell, a contract worker whose mission at the moon is coming to an end.

His vile treatment by Lunar creates a subtle juxtaposition; the central theme of the film, a utopian ideal, is given to Earth through this energy source at the cost of the torture of one soul. In this regard, “Moon” is reminiscent of Ursula Le Guin’s meta short story, “The One Who Walks Away from Omelas,” with a similar ideology despite the starkly different foundational core.

Rockwell’s performance gives a sympathetic insight into the possible consequences of an extended isolated existence. The fatalistic fortunes of the character allow Rockwell to expand in his investigation of the character and make it a contrast-filled master class.

Jones’ high-concept character study is an effective and influential work of smart writing and atomistic execution. In a world where filmmakers try to overdo and egregiously miss, Garland keeps it simple and ascetic to substantially aggrandize his reputation and the film’s significance.

4. Eternal Sunshine of Spotless Mind

Charlie Kaufman’s status as the greatest living screenwriter of his time remains uncontested. His audacious scripts over the years have made for some of the most compelling stories told on celluloid. There exist some movies that represent their genres perfectly.

The way they tell their stories – that’s how it must be told. After you’re done experiencing their charm and mystique, you feel that every other film that attributes itself to that certain genre did it wrong. “Eternal Sunshine Of The Spotless Mind” is that film.

There’s simply no better way to tell a somber romance tale than to make the lovers analyse their relationship from all the way back to when it began. Anything that went wrong during the course of their time together can be mended. Simply doing this could be boring.

For instance, you could just have both characters talk about their relationship and find out its problems. But in the hands of geniuses like Kaufman and Gondry, this simple idea doesn’t stay that way.

We go inside the head of Joel Barish, a man who – after a harsh spat with his girlfriend – finds out that she plans to erase him from her memory entirely. Feeling sad and betrayed, he plans to do the same thing to her.

The memory erasing process (that is done and was discovered by members of Lacuna Inc.) works backwards; as in, the more recent memories are removed first, then the ones that happened a while ago. And thus, in Joel’s head, we see him look back on his relationship with a version of his girlfriend, Clementine, tagging along with him. That simple story mentioned before has been executed in probably the best way ever.

This film works on many levels, and both technical and narrative aspects help it do so. It has a mysterious aura surrounding it. A sedated environment, if you will, since we are in another person’s head, and he really doesn’t want to be there anymore. It’s a beautiful romance but at the same time so downbeat and depressing.

Highly inventive, mind-bending, and heart-wrenching, “Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind” reveals a whole new perspective towards a genre, which was biting the dust back then. Kaufman’s eccentric script, Michel Gondry’s perfect direction matched with Carrey’s and Winslet’s excellent chemistry makes this movie a must-watch.

The subplots and character arcs of the Lacuna Inc. people contribute to the movie’s rich plethora of storytelling and characterization. Surprisingly sweet with a very toned down Jim Carrey, “Eternal Sunshine” is, like “The Lobster,” proof that cinema can still surprise and delight.

3. District 9 (2009)

There aren’t many indie films that have gripped the mainstream quite like “District 9.” The Neill Blomkamp-helmed film has become a sort of cult classic over the years, with Sharlto Copley going on to claim global fame as its heroic lead.

“District 9” is set in a dystopian version of the world that has seen a huge influx of prawn-like alien species, who’ve been contained in a refugee camp-like facility, functioning under strict governmental control. The ‘prawns,’ as they are called, saw their spacecraft rendered dysfunctional when they first came, with attempts to revive them unsuccessful until now.

As Christopher, his son, and Paul are on the verge of making contact with home and dream of going back, their plans are inadvertently ruined by a government officer, Wikus Merwe. In the process, Merwe gets infected and mutates into a prawn, becoming the subject of great skepticism from the authorities. He then decides to help the three prawns in their mission, hoping to become human again in the process.

With varying themes from the core of Blomkamp’s thematic structure, the social commentary in the background is a scathing attack on modern-day politics, which has increasingly become spineless and indifferent to human rights.

In the foreground, “District 9” boasts of one of the most lively and imaginative scripts to be made into a feature film in the last decade, a healthy blend of action, tenderness, and satisfying narrative arches. Its stunning depiction of the refugee crisis overlapping the world remains the key takeaway, but “District 9” exists as an immaculate and evocative classic science fiction film.

2. Hard to be a God

A film that has been described as a “bad home production of ‘Game of Thrones’ meets Monty Python’s Holy Grail” is a hard one to miss. It is difficult not to feel repulsed and disgusted by Aleksei German’s ingenious swan song.

Almost the entire film is shot in close-ups with filth and macabre and slime and snot surroundings connecting the viewer to their first impression of Arkanar, a planet visited by scientists from Earth to save an intellectual uprising. The stunted process of evolution seems incapable of tipping into the Age of Enlightenment and the Renaissance, leaving it incumbent upon the scientists to influence change.

Vladimir Ilyin and Yuri Klimenko share the credit for the luscious, unique cinematography that is bound to make viewers feel claustrophobic. While films like Bergman’s “Winter Light” and Schrader’s “First Reformed” stay boxed in with their troubled protagonists, the Russian duo try to box the viewer in, allowing them to closely and intimately engage with the disgusting visuals.

The murky tenor of the film feels aged, typical of German’s work, perfectly fashioning the medieval period in which it is set. The unique and ubiquitous use of close-ups might be off-putting to some, which works well in tandem with a cryptic script to make the whole affair a dazzling, mystical nightmare.

German’s framing is reminiscent of Tarkovsky’s, a frequently cited inspiration of the Russian director, and literally most filmmakers working today. But instead of the Russian legend’s poetic, mellifluous style, German’s camera work is disruptive and detached, resisting any semblance to conventional cinematic wisdom.

Although it is hard to ignore the monumental technical achievements of “Hard to be a God,” German’s descriptive journey into many years of human misery, brutality, and lack of self-awareness is attention-worthy.

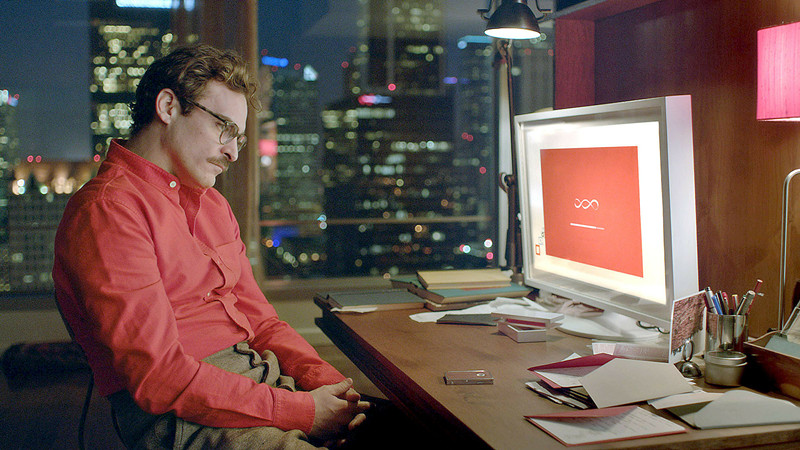

1. Her (2013)

Spike Jonze’s heartfelt sci-fi drama feels more like an ode to his broken marriage than a unique, cutting-edge modern miracle, even though it surely is. The director separated from his wife of four years, Sofia Coppola, in 2003. The ‘irreconcilable’ differences seem very well transported onto the protagonist, Theodore, and his relationship with his ex-wife. Their first meeting after their separation that we see on screen wears a rather skeptical, yet tender energy.

Joaquin Phoenix and Rooney Mara, who play the characters, bring out the emotions of their characters’ broken hearts, longing to stay with each other, but resigned to the anthropological realities of their species with aplomb. Theodore’s revelation draws bitter and almost demeaning pity from Catherine, recreating the lack of empathy in their relationship that seemed to have gloriously been rediscovered moments ago.

“Her” is a tragedy about a desolate man looking for hope in life. Through his navigation of daily life, Theodore stumbles upon a new software upgrade that provides an AI assistant with almost human-like cognitive and emotional temperament. Despite the initial hesitance, Theodore grows close to Samantha, the AI, and finds in ‘her’ a joyous filter to life, unaware of the inevitable and macabre heartbreak that awaits.

Coppola’s manifestation of her perspective of their time together in “Lost in Translation” fetched the American filmmaker an Academy Award, just like her husband. A comparative analysis of the two films not only reaffirms their remarkably similar visions, but also points toward a conspicuous similarity and inspection into how the two coped with life after.

The colors that fill the canvas of the film vary a touch, with Coppola’s film forever drenched in melancholic, morbid blue, while Jonze’s film celebrates warmth and optimism, almost in a delusional way. It wouldn’t be so wrong to say that the main characters of the films are the surrogate of each director.

Jonze’s Theodore and Coppola’s Charlotte mirror the seemingly hopeless aftermath of a broken heart of millions around the world. Their stories, though ordinary in the face of emotional hardship and affliction, resonate like no other, reminding some of their good times, some bad.